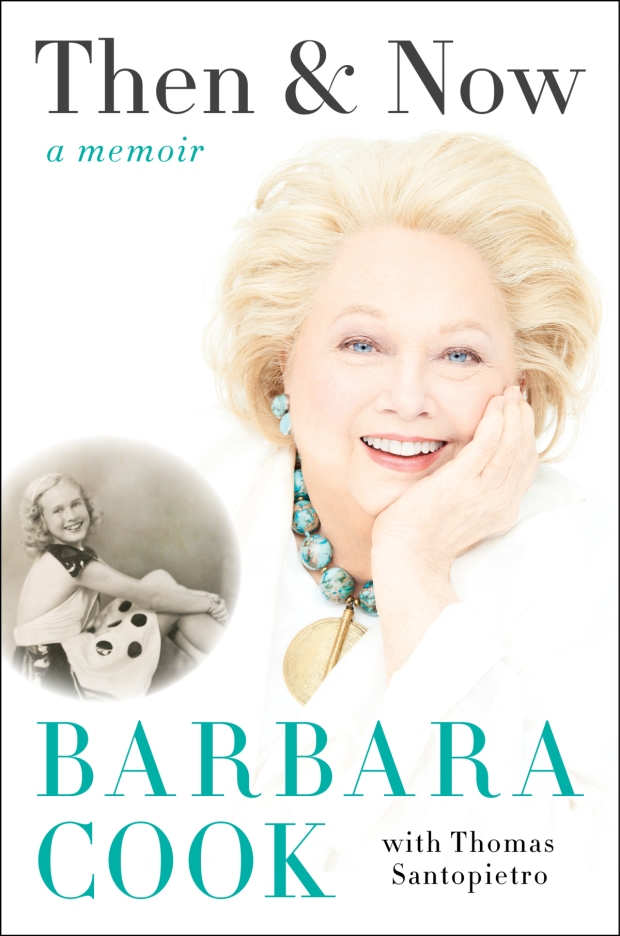

Barbara Cook on Infidelity, Drinking, and a "Difficult" Elaine Stritch

(© Tristan Fuge)

"I killed my sister when I was three years old," writes Barbara Cook in the first sentence of her memoir, Then & Now. It's a startling admission about a situation that is more complicated than it first appears, setting the tone for a remarkably candid autobiography from the Tony Award-winning star of the original Broadway productions of Candide and The Music Man.

"Most memoirs are very superficial," Cook opines. "I wasn't interested in writing that kind of book. I tried to go a little deeper." Mission accomplished: Cook writes at length not only about her long career (now approaching its seventh decade), but about her alcoholism nearly bringing it all to a halt. She also opens up about her strained relationship with another legend of musical theater: Elaine Stritch.

Although she's confined to a wheelchair, Cook still regularly performs, with two upcoming dates scheduled for Feinstein's/54 Below. She was slated to star in an off-Broadway revue titled Then & Now this past spring, but that show was postponed indefinitely. Cook discusses what went wrong in the below interview — but first, about that murder she committed as a toddler:

Did you really kill your sister when you were three?

What happened was my younger sister had just died of double pneumonia, and I heard my mother tell people that maybe she would have lived if I hadn't given her whooping cough. I was three years old, so I thought I killed her. I grew up thinking that her death was my fault. I know that's not true now, but I still live with that guilt.

When you first sang "Glitter and Be Gay" from Candide for the composer Leonard Bernstein, you suggested a change to one of the notes. How did he take that?

He immediately said, "You're right." He was terrific about that. I now think it was rather bumptious of me to suggest anything, because God, he was Leonard Bernstein and who was I? But it seemed absolutely right to me and it was a lot easier to sing. I usually decided early on how songs should be done, and I felt very strongly about it. I got a lot of those notions from Mabel Mercer, who was just a sensational performer.

In writing about the breakdown of your marriage to David Le Grant, you advise, "If you do have an affair, live with your guilt and don't tell your spouse."

Yes, I think that's the best advice, unless you want to get rid of your marriage. The best thing to do is be honest, but we can't always do that. If you want to keep your marriage, you learn to live lies.

Do you think the urge to reveal an infidelity stems from a certain confessional strain in our culture?

It's odd: Since I started writing this book, I've found that in performance I speak more and more about personal things. I never used to do that when I would talk in the act. But when you're writing a book, your brain is constantly roiling over everything, so these things are in the front of my mind. After every performance I've ever done, people have come up and said they loved hearing my stories.

(© HarperCollins)

How do you think your alcoholism affected the trajectory of your career?

It stopped me for a while. It was a big problem. One of the reasons I wrote the book is that if someone is reading it and is in some kind of trouble, hopefully they will read about my life and see you can come out of that and have a second life.

How important to that second life was your music director, Wally Harper?

Oh God, he was completely important. He died in 2004 and I still think about him all the time. Wally helped me to start singing again. I'm sorry he died so early.

You had a somewhat contentious working relationship with the late Elaine Stritch.

I wouldn't say contentious, because we never really worked together aside from one benefit at Lincoln Center. She could be difficult, but my God, she was so talented. I always thought that she and I would be good together in concert. We never did do it, but it's just as well: I think it would have driven me crazy.

Is it true that she gave herself an insulin injection right in the middle of a quiet ballad at one of your shows at Feinstein's at Loews Regency?

[laughs] Yes, she was what I would call a professional diabetic. She would constantly take shots with other people around. She was unusual that way. Most people would look for a private place, but not Elaine.

You were slated to star in an off-Broadway show by the same name as your memoir, but it was postponed indefinitely? What happened?

As we were working on it, I realized that I didn't really want to do that. I didn't want to read from my book or something like that. Mixing the two [memoir and song] didn't strike me as the right thing to do. Little by little, we ran out of time. So that was canceled.

You have a show coming up at Feinstein's/54 Below. What criteria do you use when choosing a song for cabaret?

I'll give you a perfect example: I used to go to sleep with the radio in bed with me. I don't do that anymore, but a while ago they played a song I had never heard before by Janis Ian: "Stars." The last line of that song is, "I'll come up singing for you, even when I'm down." I thought, Wow, I'd really like to say that. That's why I started singing that song. It said something I wanted to say.