COVID-19 Claims a Great American Playwright, Terrence McNally

(© Seth Walters)

The theater community was saddened this week to learn of the passing of playwright Terrence McNally, who died of complications from COVID-19 on Tuesday. This Story of the Week will explain McNally’s significance to the American theater and grapple with the unsettling feeling that he is the first of many artists who will be taken by this pandemic.

Who was Terrence McNally?

McNally was one of the most celebrated playwrights in the world, having won five Tonys (including a lifetime achievement award), three Drama Desks, and a Primetime Emmy for his TV drama Andre’s Mother, which brought a story of the surviving loved ones of a deceased AIDS patient into American living rooms in 1990.

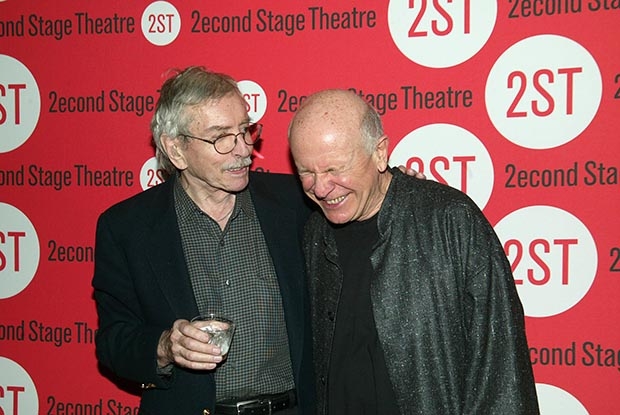

When so many Americans preferred to ignore the plight of people with AIDS, McNally refused to let the theatergoing public forget. His 1991 play, Lips Together, Teeth Apart, was about two straight couples who spend the Fourth of July at the Fire Island beach house owned by the recently deceased gay brother of one of the women. McNally further explored themes of death and atonement in his 1993 play A Perfect Ganesh, his only work to become a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize (he ultimately lost the award to ex-boyfriend Edward Albee and his Three Tall Women).

(© Joseph Marzullo / Retna Ltd.)

McNally’s plays from the early ’90s offer a stark contrast to his more lighthearted earlier work, like his 1975 Broadway breakthrough, The Ritz, a farce set in a gay bathhouse (back when such venues were still a taboo subject for polite heterosexual society). It ran for nearly a year. McNally’s transition from carefree frivolity to sober contemplation reflects the experience of gay life in the latter 20th century. McNally brilliantly brought these dual impulses together in his 1994 play Love! Valour! Compassion!, about a group of gay men who spend holiday weekends in Duchess County. AIDS is a presence in that play, but so is romance and side-splitting comedy.

McNally’s last play on Broadway was a revival of his 1987 play Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune. Gorgeously staged by Arin Arbus, and with gut-wrenching performances by Audra McDonald and Michael Shannon, it was a shining example of McNally’s ability to put both comedy and tragedy on the same small stage and force them into conversation.

(© Matthew Murphy)

Were McNally’s plays always successful?

Goodness, no. Aspiring playwrights should take heart from McNally’s perseverance in the face of criticism. Over his long career, he has received brutal notices (I’ve written some of them), and it never seemed to discourage him. The reviews of And Things That Go Bump in the Night, his Broadway debut as a playwright, were particularly harsh: Responding to that play’s repeated final refrain, “We will continue,” New York Times critic Howard Taubman sardonically wrote, “Wanna bet?”

And Things That Go Bump didn’t continue past 16 performances; but McNally did, penning dozens more plays and returning to Broadway 22 times. He was also a talented librettist, writing the books for 10 musicals, including Tony-winning masterpieces like Kiss of the Spider Woman and Ragtime. That latter title is based on E.L. Doctorow’s sprawling history of the early 20th century, which really shouldn’t have lent itself as easily to musical theater as it did under McNally’s treatment. I was surprised by how much I enjoyed McNally’s book for the musical Anastasia, which explored the very notion of truth (a concept much abused in Russia today).

(© Breaking Glass Pictures)

Those of us who have only experienced McNally’s most recent plays, like the rudderless Fire and Air or the superfluous Mothers and Sons, are quick to forget just how daring he could be as a playwright, a fact best encapsulated by the controversy that swirled around the off-Broadway debut of his play Corpus Christi, which reimagined Christ and his disciples as a circle of gay men. McNally received death threats when the play was announced, and Manhattan Theatre Club temporarily canceled the run until backlash from the theater community caused the company to reconsider.

Corpus Christi opened to protests on October 13, 1998, the day after Matthew Shepard died from injuries sustained in a brutal anti-gay hate crime. The two events remain fused in my mind, underscoring the real necessity of a play like Corpus Christi at that time. As a closeted 12-year-old living in suburban Ohio, I was silently grateful that someone was making plays with a positive message about people like me.

(© David Gordon)

Most importantly, McNally was a kind person. The few times I encountered him, he struck me as genuinely happy, which isn’t always the case for writers. His long relationship and marriage to the producer Tom Kirdahy, who is also one of the nicest people working in the theater, is further testament to the light that McNally emanated, which usually attracts likeminded folks. I’ll never forget the sight of them in their matching yellow shoes as they promoted The Visit during awards season 2015.

What can McNally teach us about the coming phase of the pandemic?

The stage is now being set for a push to end our national quarantine and return Americans to work. We ought to be particularly mindful of the arguments used to justify it, specifically the cruel logic that insists COVID-19 is a disease that mostly kills the infirm and elderly, as if their lives are a reasonable sacrifice to the gods of economics. A lung cancer survivor who suffered from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, McNally had been visibly unwell in the past year, accepting his 2019 Lifetime Achievement Tony Award with breathing tubes under his nose. He was certainly in the group most vulnerable to COVID-19, a disease that causes acute respiratory distress.

However, McNally was still writing and revisiting his plays up until the end (a revised version of Fire and Air called Immortal Longings played Houston’s ZACH Theatre last summer). I have no doubt that he had more plays in him that we will never get to hear. Right now, we really need to ask ourselves: Has the country that saw the lives of gay men as expendable during the AIDS crisis really not progressed past that point? What other marginalized groups are Americans willing to sacrifice?

As America peers over the precipice of national indifference to suffering, it feels like the cruelest irony that we have just lost one of our most compassionate playwrights. “The world needs artists more than ever,” he declared from the stage of last year’s Tony Awards, “to remind us what kindness, truth, and beauty are.” McNally saw the playwright, in particular, as the conscience of the nation. I can only hope that his artistic heirs are up to the task as we leap into the darkness.