Gilbert & Sullivan & … Frankenstein?

I've got a secret list of musicals that I wish I could see, but I know I never will, for the very good reason that they don't exist. Their creators thought about writing them but for one reason or another never did: George and Ira Gershwin's Zuleika Dobson; Kern and Hammerstein's Messer Marco Polo; Bock and Harnick's Lord Nelson musical. But far and away my favorite — are you sitting down? — is Gilbert and Sullivan's Frankenstein.

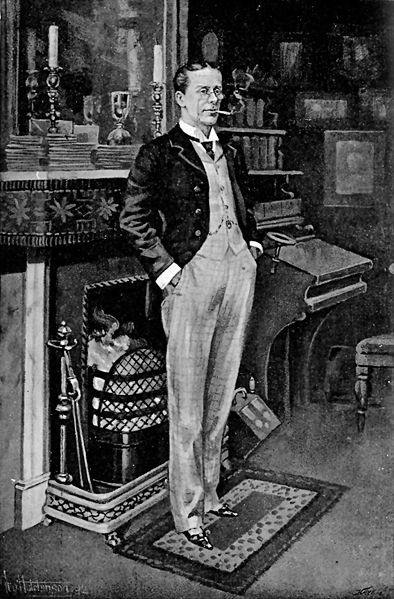

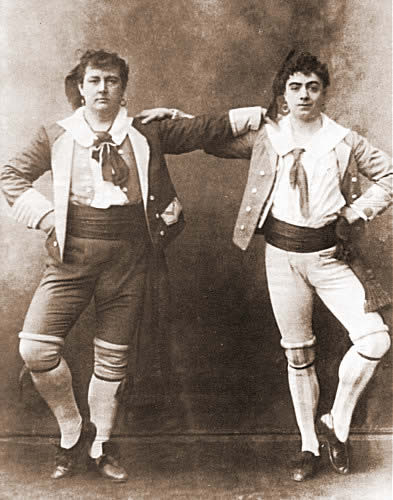

Yes, the two great masters of comic opera did discuss the notion, one of several that Gilbert broached to Sullivan as a possible follow-up to the runaway success of The Mikado. His thought was that George Grossmith, the spidery patter-singing comic who created the role of Ko-Ko, would next play the mad doctor who finds himself under the menacing thumb of the monstrous creature he had created, to be played by Rutland Barrington, the tall, husky baritone then playing Pooh-Bah, Ko-Ko's haughty abettor.

It never happened. Sullivan apparently found its musical prospects unpromising. Instead, the team wrote Ruddigore, a spoof melodrama in which ghostly portraits come to life. That work's comparative failure planted the seeds of distrust between writer and composer, which would flower, in 1890, into their famous quarrel. So we will never hear the duets Gilbert might have conceived for monster and scientist, or the wild orchestral filigrees with which Sullivan might have decorated their lab.

I was thinking about the paradox of this perfect writing team's astonishing personal incompatibility, because a date caught my eye: 124 years ago this month, W. S. Gilbert wrote to Arthur Sullivan to announce that their collaboration had officially ended. The date on which that letter was sent, as it happens, is the one on which, 55 years later, I was born. That may explain why I've always felt such a terrible sense of loss over the breakup of their partnership. I can't help but wish that Gilbert had hesitated a few days before sending the fatal letter. Their quarrel might have been mended, leaving both their later lives and mine happier and more fulfilled. (It probably didn't help matters that Sullivan was approaching 50. Gilbert's epistolary rampage began not long before the composer's 48th birthday, May 13, 1890.)

Gilbert's statement ultimately proved untrue. The two men's collaboration did not end. The breach between them was repaired sufficiently for them to add two more comic operas (though not a Frankenstein) to the twelve that had already made their conjoined names a household word. But neither their working relations nor their results seemed as assured afterward. Gilbert's letter — one of a barrage of angry letters that he sent during those stressful months in 1890 to Sullivan and to their producing partner, Richard D'Oyly Carte — had snapped the golden thread that had bound these two highly contrasting artists together for nearly two decades.

(© Ambassador Theatre Group)

The quarrel was over money, except that it really wasn't. And though the person with whom Gilbert picked the quarrel was D'Oyly Carte, Sullivan was its real target. That for them to quarrel was lunacy, both men clearly understood. When Gilbert's temper cooled, he immediately started attempting to heal the breach. And Sullivan tried too. Though his first reaction to Gilbert's letter had been to write in his diary, "Nothing would induce me to write again with him," he responded to Gilbert's peace overtures by pleading that everything would be fine, if Gilbert would only admit that he'd been wrong. (And, of course, if he'd withdraw his threatened lawsuit against Carte.) Clearly, they both knew that no angry words or legal threats could destroy what they had built together: Neither really wanted the collaboration that had already given the world The Pirates of Penzance, The Mikado, and Yeomen of the Guard to be thrown away so casually.

Gilbert's threatened legal action concerned the cost of new carpets — 500 pounds — for the Savoy Theatre lobby. At first glance, it does seem a questionable (and questionably pricey) budget item. Carte owned the theater (built from his share of the profits of the trio's earliest works), and the triumvirate, as producers, paid him a yearly rent. The unusual arrangement had worked out extremely well for all three: Gilbert provided the libretto and staging for new works as required; Sullivan supplied their music, including orchestrations; and Carte managed the theater's day-to-day operations. Once production expenses were paid off and the weekly payroll met, everything left over was divided in equal thirds. Newspaper stories at the time of the "carpet quarrel" estimated that the authors had each earned around 90,000 pounds during the previous decade.

Gilbert, however, had come of age theatrically in a time when managers were notoriously untrustworthy. While profiting mightily from the team's distinctive setup, he viewed with suspicion Carte's freewheeling ambitions and free-spending love of lavishness. A cynic by nature, Gilbert viewed everyone and everything with suspicion. The thought of having 500 pounds deducted from his quarterly royalties, to pay for new carpeting in a theater he didn't own, made him explode — not an uncommon occurrence with Gilbert, who seems to have been somewhat bipolar. He stormed into Carte's office. Heated words were exchanged. Angry letters and legal proceedings ensued.

But investigation duly showed that Gilbert's choleric temperament had played him false. The three partners' lease on the Savoy did indeed specify that they were responsible for "wear and tear" to the premises, lobby carpeting included. Examined in detail, the 500 pounds charge turned out to be a misreading; by Carte's estimate, the new carpets had cost only a reasonable 140 pounds. Gilbert ultimately withdrew the lawsuit, without reservation. Given the amount of money each was making from the hugely successful production of The Gondoliers, even the inflated sum had hardly been worth arguing about. But the dispute had exposed the underlying rift between librettist and composer, concerning which, more next week.

Stay tuned to TheaterMania for part II of this "Thinking About Theater" column, which will appear on Friday, May 23.