An Outspoken Critic Provokes Visions of Stages Past and Present

In the 1930s, London theater journalist James Agate discovered America.

A few weeks ago, to nobody's surprise, I bought a set of books. (My friends, reading this, will sigh and shake their heads; they know that my apartment already looks like the San Francisco Library after the earthquake.) I had been hunting a topic for this month's essay, but no matter what notion I toyed with, the books kept luring me away. Aside from beautiful young people, nothing is more seductive than beautiful old books.

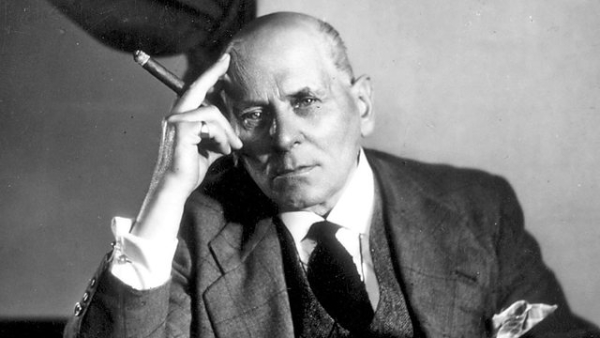

And this set, to me, was especially seductive: a complete run, in nine volumes, of Ego, the diary-autobiography-scrapbook of the great British drama critic James Agate (1877-1947), who covered theater for London's Sunday Times from 1923 until his death. I already owned several of the volumes, along with many of Agate's review collections, but I shelled out for this batch, not only because it was complete, but also for its association: It had belonged to one of Agate's few American devotees, the arts journalist Thomas Quinn Curtiss (remembered now for his biography of the film director Erich von Stroheim). Agate had dedicated one of Ego's later volumes to Curtiss. That and two of the others carry on their flyleaves lengthy, affectionate inscriptions to Curtiss, in Agate's small, precise handwriting.

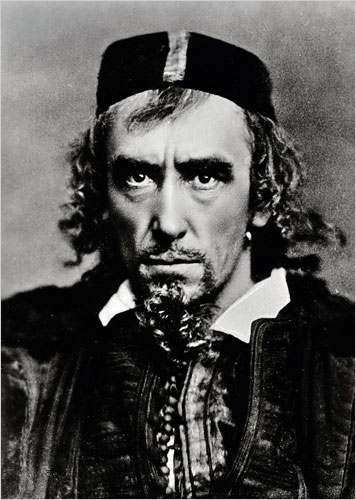

I love reading Agate and often cite him. (I quoted him in this column two months ago, on the topic of leaving shows early.) He came late to theater criticism: Born in Manchester, he spent his early adulthood in his father's wholesale cotton-cloth business, and didn't begin writing for a living till he was nearly 40. As his orotund style often reveals, he remained in many ways a Victorian. While chronicling, appreciatively, the exciting early years of Gielgud, Richardson, and Olivier, he still considered Henry Irving the greatest actor he had ever seen. Though relishing racy, colloquially contemporary writing and acting — he led the cheers for the Group Theater's 1938 London triumph in Clifford Odets' Golden Boy — he took the highly stylized French classical tradition as one of his major critical touchstones, putting Sarah Bernhardt on a pedestal as high as Irving's.

As this suggests, Agate reveled in his contradictions. Genial and spontaneously witty, he made devoted friends in all walks of life while staunchly believing that Britain's class system was irrevocable. Similarly, his fervent English patriotism never stopped him from scathing remarks about English shortcomings ("The coffee, we being in England, was undrinkable"), or from relishing other countries' artistic achievements — gleefully employing them as sticks with which to belabor substandard English work. A lover of fine food and wine who bred champion show horses, he lived chronically beyond his means (recording his tax troubles in Ego), and worked fiendishly to keep up, writing weekly articles for six periodicals besides the Sunday Times. (He fretted when his yearly output fell below half a million words.)

Agate's reviews, like those of all great critics from the past, can be sifted for their innumerable nuggets of wit, wisdom, and theater lore. The nine volumes of Ego, however, constitute a phenomenon unlike anything else in theatrical literature. Kept more or less in diary form, they naturally contain much overspill from his theatergoing: thoughts deleted from or left unsaid in his reviews; his post-review reflections; remarks, addressed to him or overheard, at or after the show. (At one intermission, a lady seated in front of him turns round and exclaims loudly, "Ah, Mr. Agate, how are you enjoying the play? I am sitting with the author's mother.")

He notes down memories the shows evoke of earlier performances, often annotated with quotes from his admired predecessors or his own earlier reviews. And he shares the reactions his reviews provoke from friends, critic colleagues, and the artists he writes about. ("You were right," Mrs. Patrick Campbell tells him about Ibsen's Hedda Gabler. "I never could play her, because I could never get the Latin out of my blood. I have had Swedish masseuses who were ten times better Heddas.")

As Ego progresses, Agate's closest acquaintances take on three-dimensionality, like figures in some giant sub-Proustian novel: his disputatious secretary, Alan ("Jock") Dent, later a noted critic himself; the perpetually grouchy retired concert pianist Leo Pavia, always ready with a malicious piece of ancient gossip. He trades quips with theatrical divas, fading and upcoming, from Irene Vanbrugh (the original Gwendolyn of Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest) to Hermione Gingold (who would go on to star in American musicals, including Stephen Sondheim's A Little Night Music). "Notable artists' deaths — the Shakespearean star Frank Benson, the music-hall comic Harry Tate — provoke long, anecdote-laden tributes.

For Agate, the theater was a continuum; his perpetual hope for its future is fused into his passion for its past. He pasted into his Ego entries not only the irritating lapses or astute observations of that day's newspapers, but floods of miscellaneous items — literary, theatrical, journalistic, criminal, or sheerly gossipy — recalled from personal experience or transcribed from ancient books and documents. Lengthy quotes, many in French, from his favorite 18th- and 19th-century writers stud the volumes. He seems to have known Samuel Johnson, Honoré de Balzac, and Charles Dickens almost by heart, along with such inevitable theater-critic resources as William Shakespeare, Henrik Ibsen, Anton Chekhov, and the standard plays of his late-Victorian youth.

Significantly, he took his beloved past as a guideline, not an iron law. Like many of his generation, he found himself struggling, in the 1930s and '40s, with modernist poetry, painting, and music. Sometimes he confessed bafflement, boredom, or sheer loathing. But he never hesitated to acclaim new work that he found good and exciting, irrespective of its approach or country of origin. One of England's first practicing film critics, he was, understandably, suspicious of Hollywood's overhyped products, and of American mores in general. (In America, he said, "moral uplift goes hand in hand with a sentimentality that would make a rhinoceros vomit.") That didn't stop him, though, from finding important values in the American theater, about which more next week.

Stay tuned to TheaterMania for part II of this "Thinking About Theater" column, which will appear on Friday, February 27.