Bert Williams: America's First Black Star

A rediscovered film at MoMA prompts reflections on a great artist’s extraordinary career.

(© Joan Marcus)

My friend Dave thinks pickled pigs' feet are racist. Well, not precisely. But I took Dave, a gifted young writer whose real name of course isn't Dave, to see the current Broadway revival of You Can't Take It With You, a play in which an African-American character, sent out to buy dinner-party food, returns with a big jar of pickled pigs' feet. Dave enjoyed the production overall, but found this joke stereotypical and demeaning. I explained to him that the joke was actually on the stuffy white dinner guests; I said that in reality, pickled pigs' feet were relished by people of many ethnic groups. I even sang him, in my inimitably off-key fashion, a few phrases of Bessie Smith's "Gimme a Pigfoot and a Bottle of Beer."

It was all no use. Dave belongs to a generation of artists determined to combat the specter of ethnic stereotype wherever it appears. Historical works that don't meet his standards must either be laundered into political correctness or deleted from the playlist. His case, passionately argued, is hard to disagree with. Fundamentally, I don't really disagree. Nobody in the arts, especially in our blue-shaded sector of America, seriously thinks that any ethnic group, religion, nationality, or gender category deserves to be demeaned. Bigotry is widespread enough without our adding fuel to its fires.

Yet — I love history. Dave does too. And for the politically sensitive, history is a minefield in which every step can touch off an irate explosion. But history's there. It can be reexamined, challenged, and explored, but not rewritten. Its facts remain its facts. African-Americans, who were demeaned and caricatured in our popular culture for decades, have a substantial complaint against it, and they are by no means alone in that regard. Which makes for a knotty problem: To declare this aspect of history a forbidden zone, and leave it unexamined, would be both dishonest and crippling; to sanitize it into politically corrected blandness seems even worse. History is memory; forgetting it is as bad as tidying it up.

Delving into that forbidden zone, though, brings dangerous temptations for the cultural explorer. What starts as a serious study of historical materials can lead to reveling in them, even to unintentionally widening their circulation, setting their imagery loose without the needed scholarly context. And along with those who would exploit the stereotype images, one has to fend off the people who adamantly believe that such materials shouldn't be studied, and their imagery never displayed, at all, with or without context. Compared to them, my friend Dave, wishing the pickled pigs' feet would disappear from You Can't Take It With You, is a relatively mild case.

I felt Dave's pain all the more intensely when, a few days after our pigs'-feet debate, a fragment of our troubled cultural history made front-page news: The Museum of Modern Art announced that it had unearthed a hitherto unknown and unreleased 1913 feature film starring Bert Williams (1874-1922). Part of a vast collection acquired by MoMA's film department in 1938, when the silent-film giant Biograph Pictures went out of business, the footage appears to contain the complete unassembled rushes of this unseen film for which apparently no titles or script survive. The first public screening will be held at MoMA on November 8. An exhibit assembled around it, containing stills, period photographs, and ephemera of Williams and other artists involved, runs October 24-March 15, under the bittersweet title 100 Years in Post-Production: Resurrecting a Lost Landmark of Black Film History.

Theater buffs unfamiliar with Bert Williams may wonder what makes this discovery so spectacular, and what it's doing in a theater column. Williams' extraordinary career answers both questions. A pivotal figure in the evolution of the American musical, he was both Broadway's first black star and the nation's first black recording star. In vaudeville, and for a decade as lead comedian of the Ziegfeld Follies, he commanded a huge salary, said to be larger than that paid to the President of the United States. Posters and sheet-music covers made his tall, slightly stooped figure, in his vaudeville costume of battered top hat, worn frock coat, and ill-fitting trousers, a nationally recognizable icon. His hit song, "Nobody," which he also cowrote, remains a perennial, recorded to evoke his spirit by artists ranging from Carol Burnett to Johnny Cash and Merle Travis.

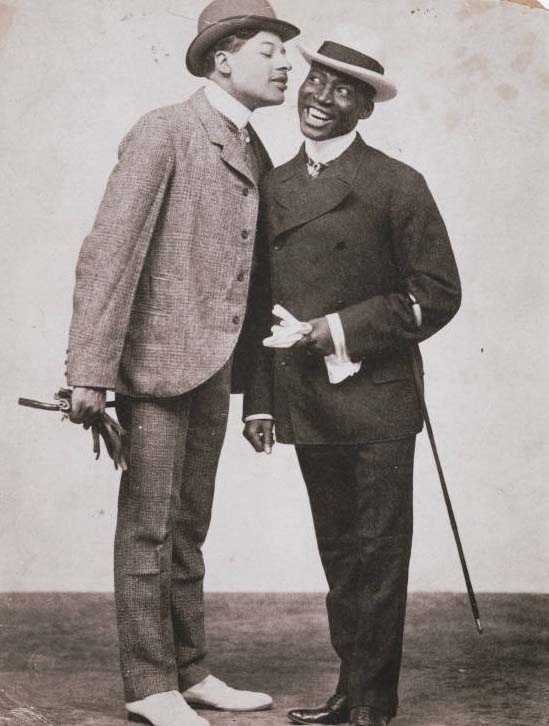

And Bert Williams achieved all this — hear the political correcters groan — while wearing blackface, that most hated insignia of ethnic stereotyping. In his early career, working black vaudeville circuits as a "double act" with the brilliant George Walker (1872-1911), the duo affirmed their superior authenticity to that of blacked-up white men by billing themselves as "Two Real Coons" (emphasis on the adjective). Walker, over time, gradually did away with the blackface. For the light-skinned, Bahamas-born Williams, it became a liberating mask, behind which he could create a seemingly infinite panoply of comic effects that in his later years as a solo act, following Walker's shockingly early death, deepened into something approaching tragicomedy.

I'll say more about his accomplishments, and the resonance his artistry holds for us, next week. Meantime, in addition to the MoMA exhibit, you might find it worthwhile listening to Williams' recordings, available on Archeophone CD.

Stay tuned to TheaterMania for part II of this "Thinking About Theater" column, which will appear on Friday, October 31.