Ibsen the Inevitable

"So," my editor said to me, "this year is Arthur Miller's centennial. What kind of piece are you going to write?" "Well, naturally," I said, "since it's Arthur Miller's centennial, I've got to write about Ibsen."

Yes, dear reader, my editor gave me the same puzzled look that you're probably giving your computer screen right now. I tend to say things that provoke puzzled looks. I can't help that; it's just the way my mind works. And when this throws me out of kilter with people's commonly held notions, I console myself, in part, by thinking that Ibsen's mind apparently worked that way too. He was always, daringly and alarmingly, seeing things from an angle that startled his contemporaries. He taught me to think at that angle without fear, just as he had taught Arthur Miller and all the rest of the modern drama's creators. Without him, we would not have the theater we have today.

So here's to Ibsen. As I had just been teaching my theater history students about A Doll's House and Ghosts when I went to see the new Broadway production of Arthur Miller's A View From the Bridge, so my mind was steeped in his work. Suddenly Miller's powerful play seemed suffused with Ibsen, particularly A Doll's House. Here was Catherine, the beautiful niece whom Miller's hero, Eddie Carbone, has raised, complaining of being overprotected and treated like a child. (Miller uses the '40s pop song "Paper Doll" as a significant artifact.) Here she was, feeling equally devoted to Eddie and imprisoned by him, affectionately lighting his cigar — the way, as I had been pointing out to my class, Nora Helmer in A Doll's House lights Dr. Rank's cigar.

I saw more of the mark that Ibsen had left on Miller, a few days later, at the Signature's off-Broadway revival of Miller's 1964 play, Incident at Vichy. I wasn't yet steeped in Ibsen when, as an undergraduate, I saw Harold Clurman's original production. The play's "social" aspect — its ethical and political discussions — seemed then to overshadow its psychological grounding; the work was widely perceived then as talky and message-y. Time has altered that. Michael Wilson's new production isn't better per se than Clurman's, a surprising amount of which still lingers pleasurably in my mind, but it's more willing, one might say, to let the personal seep into the political.

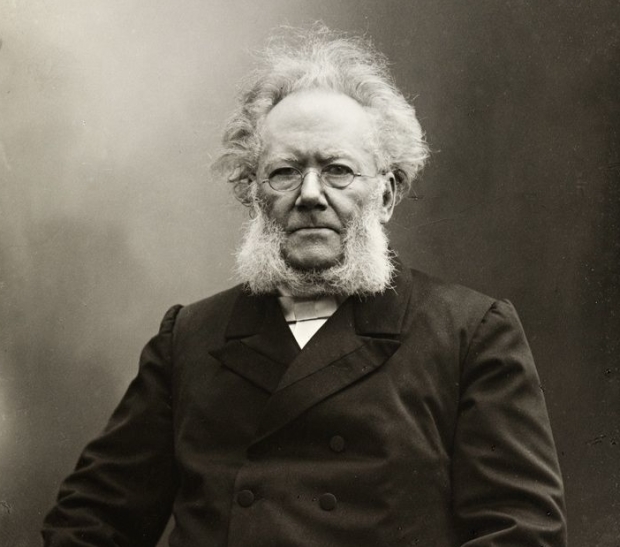

(© Joan Marcus)

For this was Ibsen's great discovery. He perceived not only that the personal is political, as we all know now, but that this realization could be drama's driving force. His brilliant deployment of it became his great gift to the theater. Characters in classic drama had had psychological substance, but they had not lived in a modern industrial society, where every individual's reality is organically tied to the whole. Orsino and Olivia can sort out their love affairs without reference to the foolishness of Sir Toby and Malvolio; what happens between Nora and Torvald cannot be sorted out without reference to Krogstad, Mrs. Linde, and Dr. Rank. Ibsen understood theatrically that we had become a world of interlocking parts; Miller belongs to the flood of later playwrights who absorbed his understanding.

Miller's first Broadway success, All My Sons (1947), was a modernization of Pillars of Society (1877), the first of the 12 "domestic" plays in which Ibsen tested his newfound perception in a naturalistic apparatus. Over the next quarter-century he would, like Miller after him, strengthen it and test it further, alternately tighten and expand his focus.

Though concentrating on one family, Pillars of Society brings the whole community into play, as does the more familiar play that followed Ghosts, An Enemy of the People (1881), of which Miller also made an adaptation. Written partly in anger over the hostile public reception of Ghosts, Enemy of the People is another of those Ibsen plays that seem to apply everywhere, in perpetuity. Last year, Criterion released on DVD an excellent 1989 film version in Bengali, by the great director Satyajit Ray, that resets the action in modern India.

To find in Ray, maker of such wide-ranging films, another Ibsenite was no surprise. Ibsen is everywhere. If you take the possibilities of dramatic narrative seriously, if you are fascinated by the ways in which humans face — or fail to face — the basic facts of their lives, you can learn from Ibsen. Distant as we are from his time, the situations he pinpointed keep arising. (I'm still wondering why, in the shadow of Bernard Madoff, nobody here has revived John Gabriel Borkman.)

Conservative critics in Ibsen's own time dismissed these newfangled studies of Norwegian life as "parochial." But time has proved that Ibsen's parish extends worldwide. In 1920s China and Japan, emancipated women were referred to as "Noras." Seven decades later, one of my great Ibsen experiences was a superb performance of A Doll's House given in Urdu by a Pakistani company — the first time the play had been staged in that language. The production had toured Pakistan's major cities; I saw it in Oslo, at Norway's National Theater's biennial Ibsenfest, which brings together Ibsen productions from around the world.

Transposed into a Muslim cultural context. and consummately acted, the play hit home vibrantly, resonating for a new sector of today's world as it had resonated for Europe and America when it premiered. One cast member told me later that the company had worried about certain passages going too close to the edge for Pakistani theatergoers. It probably would be too dangerous to play there today, when extremist violence has riven the populace. How would the people who shot Malala Yousafzai react to Nora Helmer?

Extreme reactions come with the territory that Ibsen mapped. He was unafraid of them, and they have burned their way into the performance history of his plays. In one famous instance, on January 22, 1905, the Moscow Art Theatre was playing An Enemy of the People, with Konstantin Stanislavsky as Dr. Stockmann, on tour in St. Petersburg. That day, a peaceful demonstration in front of the Czar's Winter Palace had been fired on by the Imperial Guard, killing a large number of unarmed protesters.

And that night, in the last scene, when Dr. Stockmann sees that his coat has been torn in the melee of the town meeting, Stanislavsky spoke the line, "One should never wear a new coat when one goes out to fight for justice and truth." To his amazement, the line provoked a huge uproar that stopped the show. Guards from the square outside rushed in to quiet the crowd. The next day, Stanislavsky was summoned to the censor's office. Several "provocative" lines were removed from the text; from that point on, whenever the Moscow Art Theatre performed An Enemy of the People, a bureaucrat sat onstage, following the script, to make sure no unauthorized lines were reinserted.

That story is about conditions in Czarist Russia, but it's also about Ibsen, about his power to perceive and to arouse great wells of dormant feeling, not only over social issues but over individuals and their actions. The way he inspired our theater, through his deep-searching and expansive vision, is something I'll have more to say about next week.

To read part II of this "Thinking About Theater" column, click here.

Michael Feingold has twice won the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism, most recently in 2015 for his "Thinking About Theater" columns on TheaterMania, and has twice been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Criticism. He serves as chairman of the Obie Awards and has also worked as a playwright, translator, and dramaturg.