A Carol Faintly Heard

I am not, overall, much of a Christmas theatergoer. I've managed to avoid A Christmas Story, Elf, and all versions of both How the Grinch Stole Christmas and It's a Wonderful Life. I did once attend White Christmas (everybody loves Irving Berlin) and, eons ago, Here's Love (I was a theater-hooked undergrad then and saw everything). I've survived multiple renderings of more somber holiday offerings like The Gift of the Magi and The Long Christmas Dinner (currently on display as the first half of A Wilder Christmas at St. Clement's), but by and large, as I say, I tend to dodge holiday entertainments, particularly in their commercialized form.

Like everyone else, though, I've sat through at least 11,000 versions of the granddaddy of them all, Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol. Lately its omnipresence seems to have waned a little; it used to take up around one-seventh of the production time at most of America's resident theaters. New York's only 2015 professional encounter with it came on radio, via WQXR's annual live broadcast reading, this year with Kathleen Turner as Scrooge.

I felt slightly sad at this waning because the holiday cheer-makers owe Dickens: It was he who invented the idea that Christmas entertainments should be about Christmas. Until he published A Christmas Carol in 1843, the holiday tales that people told or read aloud at the family fireside were the grim or scary kind. (The tradition lingered into the 1890s: Conan Doyle's A Study in Scarlet, the multiple-murder novella in which Sherlock Holmes made his literary debut, first appeared in a magazine publisher's Christmas annual.) And "pantomimes," the pun-filled variety entertainments that Victorian kids enjoyed as holiday treats, were strung on standard storybook tales: Aladdin, Dick Whittington, Robinson Crusoe. When Chicago had the nation's worst theater-fire disaster in 1903, the holiday treat on view was Eddie Foy Sr. in Mr. Bluebeard. (Chicago's holiday traditions now include the annual production of Burning Bluebeard, currently in its third season, which dramatizes the event.)

From his predecessors' fireside tales, Dickens annexed two standard tropes: ghosts and the irrevocably black-hearted villain. But he added a new twist: the villain's reform, linked narratively to the holiday's celebration and thematically to its spiritual meaning. Scrooge's change of heart after his night of ghostly visitations is a rebirth of love in him that parallels the rebirth of hope in a dark world. The holiday, like the decorated tree that's become its symbol, is a pre-Christian holdover: Christianity simply poured its dogma into what had been the pagan celebration of the winter solstice.

Far from negating Christmas' doctrinal meaning for Christians, that truth simply reaffirms the deep need in us to which it speaks. On the shortest day of the year, when darkness prevails, we can all be forgiven for momentarily doubting that long days of sunshine will ever come again. We need to believe that there will be another summer another harvest; those who wish to add to the occasion their specific belief that a star shone over Bethlehem and a child born in a manger came to save the world are welcome to add that thought to the general need.

They're welcome because we are all afraid, not necessarily that it is dark now, but that the light may never come again. Every time a chorus launches into "For unto us a child is born" at one of this month's 12 billion performances of Handel's Messiah, every time the boy soprano with the prop crutch fakes limping to the door, in one of the innumerable church or school performances of Menotti's Amahl and the Night Visitors, to tell his mother that outside there is a king with a crown, and most of all every time Scrooge finally shouts, "Merry Christmas!," our fear of the darkness remaining permanent ebbs a little, and even atheists may feel better.

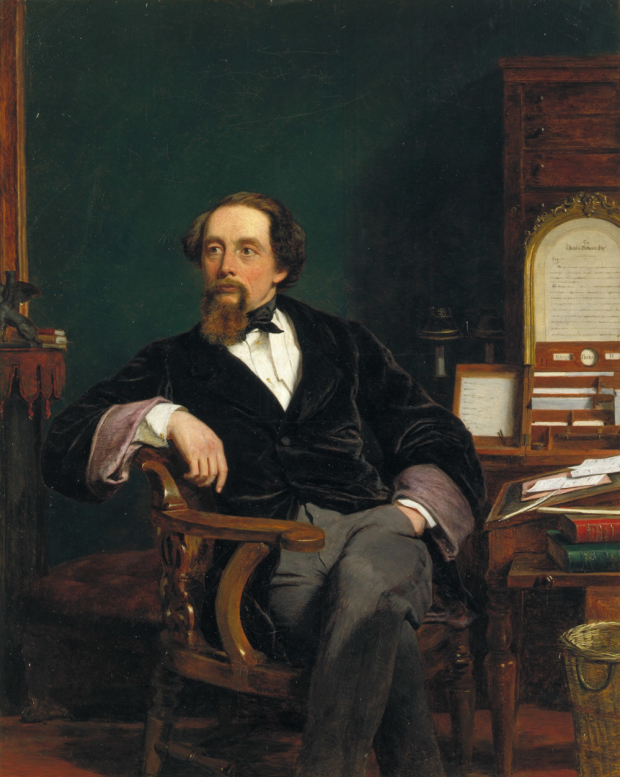

Dickens dug deep into himself to find the link that made his ghost story one of the irrevocable Christmas myths. Only 31 when he wrote it, he had already become one of the world's major cultural figures, a person of stature, wealth and influence — he had learned how much influence just the year before, on his first visit to America, where he was lionized like a rock star. He had also, by then, glimpsed the misery of the working poor while savoring his newfound upper-class luxury.

(© Evan Hanover)

Virtually no one knew then, and most of Dickens' admirers only learned years after his death, that the disparity of those worlds caused him a secret pang that stabbed him deeply. For Dickens, though genteelly raised and well-educated, had suffered the direct experience of child labor. Not long before his 12th birthday, his father had been confined to the Marshalsea Prison for debt. Most of the family moved there with him; Charles was put out to board while working, 10 hours a day, six days a week, pasting labels on pots of "blacking" in a boot-polish factory.

Though brief, that experience burned a deep groove of shame and anger into Dickens' soul. The trauma probably aggravated the natural bipolarity of the sensitive, theater-loving boy whom the other factory lads called "the young gentleman." It burned in him, still kept secret from nearly everyone, through another 20 years of creative turmoil, infusing itself into the stark contrasts and dual-natured characters with which his works teem: Oliver Twist haled from Mr. Brownlow's comfortable home back to Fagin's den. Often, Dickens' "high" characters have secrets that gnaw at them till they're dragged to a "low" destruction. Among the most intriguing is John Jasper, in the unfinished Mystery of Edwin Drood — a respectable Christian cathedral chorister who is also an opium addict and, most probably, a Kali-worshiping ritual murderer.

All Dickens' stories, in some way, echo the dualism of Scrooge's. His characters struggle toward goodness and peace, honesty and charity, but often sink under the weight of their own wrongdoing. Edmund Wilson, in one of the most influential essays ever written on Dickens ("The Two Scrooges," collected in The Wound and the Bow), jokingly suggested that in real life, Scrooge would relapse into miserliness and demand his presents back. A Christmas Carol "owes its power," Wilson writes, "to the fact that most of us feel ourselves capable of the extremes of both malignity and benevolence." Dickens knew that we most need a glimpse of light in the darkness of our own selves, and of our own time. More on that point, and its theatrical ramifications, next week.

To read part II of this "Thinking About Theater" column, click here.

Michael Feingold has twice won the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism, most recently in 2015 for his "Thinking About Theater" columns on TheaterMania, and has twice been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Criticism. He serves as chairman of the Obie Awards and has also worked as a playwright, translator, and dramaturg.