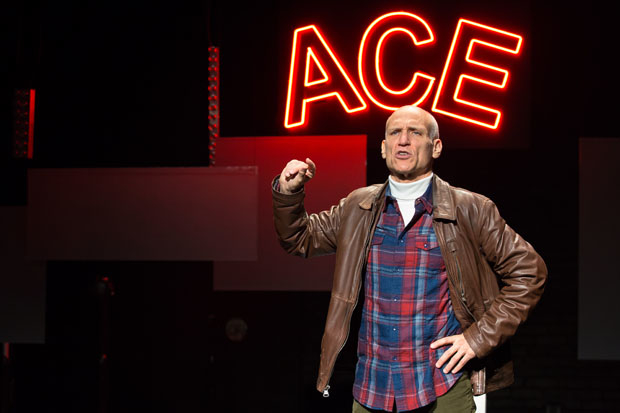

Ace

(© Hunter Canning)

It is one of life's great ironies that children often turn out to be living mockeries of their parents' values. So it is for Ted Greenberg, whose solo show, Ace, concerns his relationship with his dad, the late Alan "Ace" Greenberg, one of America's most prominent captains of finance. The younger Greenberg is a stand-up comedian, but as he demonstrates in this one-hour show at the Marjorie S. Deane Theater, not a very amusing one.

The title of the play is taken from the senior Greenberg's nom de guerre. He was a Wall Street legend: a trader who kept a deck of cards on his desk, tacitly acknowledging that his job was nothing more than legitimized gambling. The Oklahoma City transplant rose from clerking at Bear Stearns for $32.50 a week to running the place as C.E.O. and chairman of the board by the end of his career, making him a real American success story.

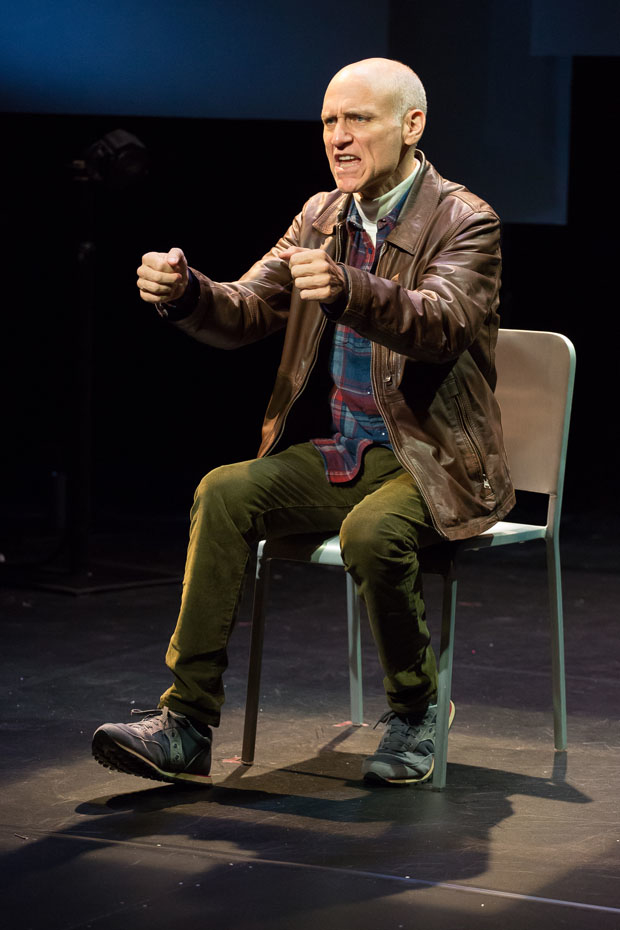

(© Hunter Canning)

Unfortunately, Ace isn't so much a story about him as it is about his disappointing son, our writer and performer. Despite having won an Emmy for his work on Late Night With David Letterman in 1984, Ted Greenberg finds himself driving a cab by 1987. "I hate TV. I quit," he tells us, justifying his decision: "When I write, I aim for something timeless…Like the great American novel and not for some flash in the pan pretender like David Letterman."

Of course, he hasn't been writing much of anything when he receives a letter from his alma mater, Harvard University, informing him that unless he turns in the paper on Edmund Spenser he's been putting off for nine years, he will never receive his diploma (an asterisk on his transcript has kept his graduation on hold). He weighs whether to spend his day finishing the paper or trying to book 50 fares in one day. "Sure I could have had a diploma," he muses, "if I were a status-symbol suck-up, desperate for validation from the man."

Greenberg may look back on his impetuous younger self with the wisdom of hindsight, but it's hard to tell what that is given his consistently stiff performance. Most jokes land with a thud as he rushes through important passages, rendering them barely audible. At one point, he mimes dialing a payphone by stabbing his fingers at a strangely high level above his head.

The sections in which he discusses his father feel like throwaway late-night comedy sketches, like the segment in which Ace coaches his son's swimming: "OK boy, I’m going to stand right here, on the bank of the Red Sea," he says from the edge of their country club pool. "Don’t give up! The Egyptian enslavers are closing in! Pharaoh’s right behind you." This moldy borsht-belt humor substitutes for a real contemplation of the father-son relationship, so we are left to figure it out on our own: While we are able to discern that Ace is vaguely disappointed by junior's life choices, he's practical enough to know that it doesn't really matter because he will always be rich enough for both of them.

(© Hunter Canning)

Director Elizabeth Margid tries (and mostly succeeds) at making this low-stakes memoir accessible for the audience. She has devised a nifty convention for every time Greenberg picks up a fare, having him spin around the metal chair that is the central feature of Guy de Lancey's minimalist set. De Lancey also designs the lights, which resemble the passing of synchronized traffic lights on a busy New York City avenue. Becky Bodurtha's costumes Greenberg in a brown bomber jacket over a plaid shirt to offer a strong sense of time and character, while Luqman Brown's sound design evokes a cartoon world that would really pop if inhabited by a comedian that had a better sense of timing or delivery.

Of course, no amount of comic acumen could compensate for a plot that tells the story of a child given the advantages of prep school, Harvard, and a home right off Fifth Avenue, only to thumb his nose at it all by chasing his boho pretentions in a taxi cab. Still, it wouldn't vex us so much if something artistically inspiring had grown out of Greenberg's road less traveled. Unfortunately, all we get is an instantly forgettable solo show, the likes of which could be seen at any given fringe festival.