Animal

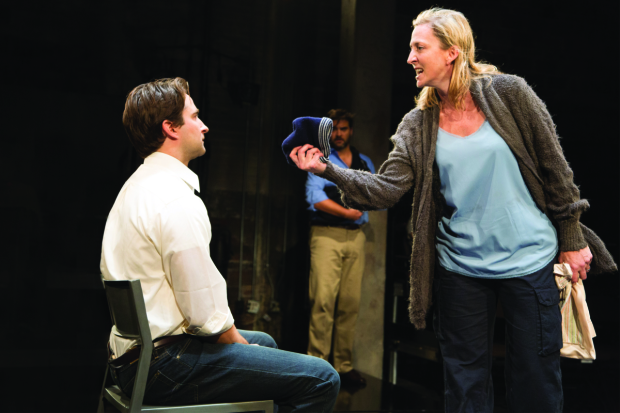

(© Igor Dmitry)

Animal, now having its world premiere at Studio Theatre, is an extraordinary new work by Clare Lizzimore that makes its heroine thrash through the weeds of mental confusion and alienation, avoiding people who try to help her, until she is strong enough to swim on her own. It is a brilliantly plotted, cleverly written play that does not finish anywhere near where it begins.

Animal is set in the home of modern young couple Rachel (Kate Eastwod Norris) and Tom (Cody Nickell). Major tensions between them are immediately apparent. The minute Tom leaves for work, Rachel's high anxiety breaks out. She's afraid of something, but can't tell what it is. She can only try to calm her nerves by grabbing a cigarette, which she promptly stomps out because she has promised to give up smoking.

Rachel has told Tom she will visit a therapist who will help work through her problems, and she grudgingly attends the sessions more to have something to do than because she believes in psychiatry. She remains aloof and insouciant with the therapist, Stephen (Joel David Santner), refusing to become engaged in his questions.

Part of Rachel's problem is existential: She doesn't understand why anyone does anything when human activity is so useless, while the other part of her angst is related to a particular sickness (one that is not revealed until the end of the play).

Norris is brilliant as the manic Rachel, self-aware enough to know that she is in big trouble, sensible enough to be able to laugh at the ridiculous situations in which she finds herself. Norris allows herself to find the humor in Rachel's life as an antidote to its pathos.

Nickell is a strong presence as Tom, who is always available to help Rachel. He even invents a "night out" for them by buying a bottle of wine, cooking Rachel a fine meal, and pretending they are eating in a superior restaurant. But Rachel is not ready for such civilized treats and destroys the illusion.

Stephen, too, is outplayed by Rachel. He tries to make her talk about her emotions, but she feels attacked by his subversive entry into her preconscious. Santner plays Stephen as a cool, calm presence, doing nothing to rattle Rachel and letting her come and go as she pleases. The third man in Rachel's life, Dan (Michael Kevin Darnall), is known for his breaking-and-entering skills. Whether he is real or a fascinating figment of Rachel's imagination, Dan is the only truly straightforward voice for Rachel – and the only one she wants to listen to. Darnall plays Dan as a cocky but charming con man who acts as a foil to the serious Tom and Stephen. After breaking into her house one night and kissing her passionately, Dan threatens to come back the next night for a second kiss — a threat to which Rachel does not protest.

There are two more characters who may exist only in Rachel's imagination. The first is Tom's invalid mother, who is permanently confined to a wheelchair and is only able to point and grunt. Rosemary Regan valiantly carries out this role. Anaïs Killian excellently takes on the mysterious role of the Little Girl in Rachel's life.

Gayle Taylor Upchurch's direction perfectly matches Lizzimore's style. The direction is fast and punchy, and it never strays too long in one direction. Set designer Rachael Hauck erected a raised, glossy black square of playing space in which the action takes place, with gray metal chairs depicting Rachel and Tom's living room and kitchen, Stephen's office, and a park. Lighting designer Jesse Belsky creates sudden blackouts to separate one scene from the next. Kathleen Geldard's costumes embody the feel of each character, from Tom and Stephen's suits and Dan's basic gray shirt, to the sweatpants, shapeless sweater, and blue ski cap that further illustrate how Rachel has given up on the world.

Clocking in at a breezy hour and 15 minutes, Animal might be short, but Lizzimore says more about our own self-knowledge and awareness in that brief time than most playwrights do in three long acts.