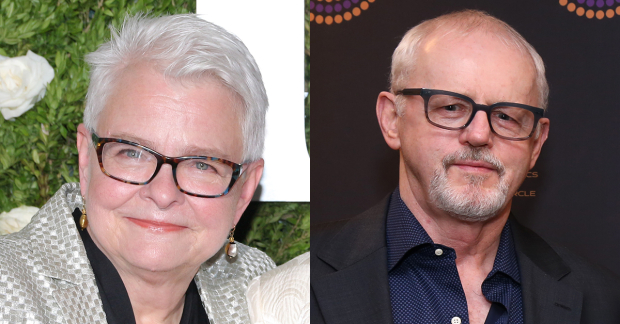

Interview: How David Morse and Paula Vogel Relearned to Drive

Vogel’s ”How I Learned to Drive” makes its long-awaited Broadway debut after 25 years, and leads its cast and playwright to Tony nominations.

Twenty-five years is a long time for an off-Broadway-to-Broadway transfer to happen, but in the case of Paula Vogel's How I Learned to Drive, the wait was worth it. The Pulitzer Prize winning play is now running at Manhattan Theatre Club's Samuel J. Friedman Theatre after an initial run at the Vineyard in 1997, and it has earned Vogel a Tony nomination for Best Revival of a Play, and acting nods for longtime stars Mary-Louise Parker and David Morse. Here, Vogel and Morse dig into the depths of this storied work, and discuss all the fears that come with remounting a show two decades later.

(© David Gordon/Joseph Marzullo)

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Take me back a quarter of a century and longer. Paula, what's your origin story of this play?

Paula Vogel: This play had been in my head since I was 20, and I would always think "How the heck would I do this?" I went, for a while, down the rabbit hole of Lolita. I wanted to see if there was a way to do it from Lolita's point of view.

I started driving one day, and I saw a young woman adjusting the rear-view mirror, and I saw the ghost of a man materialize in the back seat. Rally kind of wigged me out. But that was it. By chance, I had done a lot of research to write a play for Cherry Jones for the Perseverance Theatre in Alaska on a Pew grant.

I had worked with Cherry on The Baltimore Waltz. I was futzing around with the cast, and I skipped across the room and Cherry said, "Oh my God, girl, the way you jiggle." And I swiveled around and said, "I'm going to write something so you know how that feels." Not that that was the only initial impulse to write this. And what's interesting, I hadn't remembered that her childhood nickname was "L'il Bit," which is a common nickname in the south.

As we were about to get on the plane, Cherry called me and said, "I just got offered The Heiress." I landed in Alaska and everyone's like "Hey, where's Cherry?" And I'm like "Good news, bad news. Cherry's going to Broadway, that's the bad news. The good news is, I have a play about an uncle."

What was it like for you to hear the play aloud for the first time?

Paula: I associate this play with a type of silence that I hadn't experienced before. We did one reading in Alaska, and when we finished, there was absolute silence. I thought they were going to stone me. Then, [artistic director] Molly Smith came up to me and said, "This will run forever." I was really stunned. I couldn't get arrested in New York at that point, but Doug Aibel at the Vineyard read it overnight and offered me a slot. I remember that quiet in the audience at our first preview, and I think I went backstage and said, "We're going to get stoned," because that's what I thought. I don't know if you worried about that.

David Morse: I think part of it is, forgive me for using this word, the genius of your play. People are drawn into it in a way that they just don't expect, and as they get deeper and deeper in it, they're holding their breath. You've got them laughing, you've got these amazing characters, and there are all these little steps you take until you get them to those final moments, and it kills them emotionally. But then, at the end, the grace. That you leave them with even a little bit of humor. You give them hope to heal. What else could they do but be silent? It's the power of the play. I really do remember the power of it in that room. You can just feel it. And that power has only grown stronger to this very day.

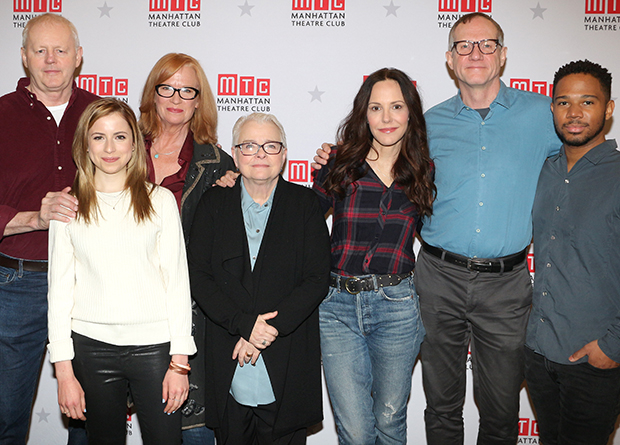

(© Jeremy Daniel)

David, what is it like to do this play now, 25 years later, when our cultural vocabulary for child abuse and pedophilia and grooming is infinitely more expanded than it was?

David: I was afraid of doing it now because I'm so much older and I was afraid people would just either be totally grossed out or it would be so offensive to have this older guy doing this that it would be unbearable for them to watch. There's so much anger at men now, and it should have been there all along because of the abuse they've inflicted on women and children for centuries. I was afraid I was going to come in and be representing all those men and all that abuse would be unforgivable.

Paula: The secret for me in the play was that I loved my uncle. I felt love for my uncle. I felt glad when I wrote it because I could see him again, rather than compartmentalizing him as this demon who caused me this much pain. I could go back and look at it as gray, rather than black and white. That was my worry about the politics of this. People have to understand that there are childhood states of needing love, needing to be desired, and needing to be taken care of, as part of this.

David, you're the only person who can pull off the idea of, "Can we feel sympathy, empathy, and desire for this man?" And if the audience can, we can understand the kind of Stockholm Syndrome that goes on with children who do feel love and do feel loved. That there is something that feels reciprocal. Not in all cases. But in cases where children are being groomed, they do feel the desire, they do feel the love.

David: In some ways, I feel like in the first production, because we were younger, it was easier for people to get swept up in that story and in that relationship, and I think it's the power of your play. I won't take credit here, because as far as I'm concerned, I'm only doing what you wrote, but even with our ages, in this day and time, they still get swept up in it. And I'm glad they do.

Paula: I feel even more urgency this time around to say that this is a syndrome that will happen and happen unless we, as parents and aunts and teachers and family members and neighbors, are vigilant. We cannot afford, as adults, to be naïve and not watch. A lot of pedophiles marry in the hope that this will stop the urges or will channel the urges. Also, family members around someone who's exhibiting pedophilic impulses need to be vigilant, as well. In a strange way, I feel like my original funny tagline that nobody would allow me to use is truer than ever, which is "It takes a village to molest a child." That's really true. What kind of help can you get for men, so they don't give in? I'm curious if people do chart or recognize, David, how hard Peck fights against it.

David: It's my hope that they do, because that's one of the things I wanted to focus on this time, and in a way, I don't think I got it the first time. He really fights against it. He did something to L'il Bit when she was younger, and he has paid the price. In terms of their relationship, he violated her, but he also violated the fact that he truly loves her from the day she was born. And he said, "I'm not going to do anything you don't want to do," so he is really battling it, in a way. But he's also doing the stuff he's doing with the hope that someday this will become more than just a sexual affair. He proposes to her, and he really is in love with her, and he doesn't want to destroy that again.

(© David Gordon)

Do you all feel an added pressure knowing that you've come back to this with the history you all have?

David: Completely. I really felt intimidated by that production and the younger people that we were. It was such a phenomenon in the city when the play opened at the Vineyard. It sold out immediately and it was one of the must-see things in New York for a year, though Mary-Louise and I only did it for six months. I just didn't know if I could personally measure up to whatever that young man did. I'm still not sure I can, but I think maybe we've done pretty good here. When I see friends after the show, people can't speak to me. People who think they're tough literally can't speak to me because they're so moved by this play. So clearly, whatever we're doing is working and I have faith in that.

Paula, I know you've reworked things here and there for this production, particularly the ending, where she no longer reveals her age. Can you talk about that?

Paula: I wanted to change it so that it would be the most flexible going forward for anyone who plays it. Because the truth of the matter is, if you're telling the story to an audience, decades have already passed, and it doesn't matter what age you are. I wanted to emphasize the gap but make the age ambiguous so that it would fit any performer. I feel that writers are basically tailors, and every actor deserves a bespoke suit.

The other thing we talked about is how we could do a framing device that's 2022, so that we're talking about what is existing right now, rather than doing a road trip back to 1997.

And then the last thing I've come to, and which is fairly important, took me 25 years. And it's my response to what David has given me. The grace and the humanity of his Peck has given me the ability to say, "There's one forgiveness that matters, and that's the forgiveness of self."