Sound Designer Jessica Paz Talks About the Art Behind the Things You Hear in the Theater

Paz was the first woman to win a Sound Design Tony, for her work on ”Hadestown”.

(© Matthew Murphy)

For every performer who steps into the spotlight as the curtain rises, there are hundreds of people working behind the scenes to make the magic of theater real. From dressers to spot-ops, house managers to stage door attendants, and everything in between, it truly takes a village to put on a show. This is the third in a series of articles designed to introduce you to the many unique theater professions you might not realize exist.

Sound design is one of the youngest stagecraft disciplines, as technical advancements made it possible only long after other disciplines were in practice (microphones didn't exist in Ancient Greece, after all!). Microphones began to filter into use on the Broadway stage in the early 1960s, and the last musical to tread the boards without amplifications was 1970s The Grass Harp. Since then, almost every sound an audience member hears coming from the stage is monitored and amplified by a sound designer and their team.

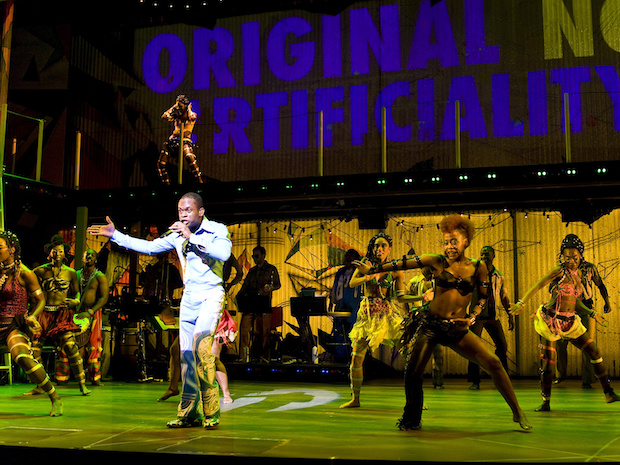

Jessica Paz, whose work can currently be heard in Hadestown at the Walter Kerr and in Little Shop of Horrors at the Westside Theatre, talked with TheaterMania about this vital profession. Known for her ability to seamlessly integrate prerecorded sound and carefully constructed soundscapes, Paz is part of a wave of sound designers who use their technical skills in increasingly creative ways. In 2019, she became the first woman to be nominated for and win the Tony Award for Best Sound Design (created in 2007) for her work on Hadestown.

(Courtesy of Jessica Paz)

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

What inspired you to enter this profession?

Jessica Paz: I had a friend who performed in The Rocky Horror Show every Saturday night at a local regional theater, and I went every weekend to support her. Spending money every week for a ticket was getting expensive, so I started volunteering. Eventually I became a stage manager for them, and there was trouble with the sound, so I stepped in to see if I could help. I fixed it, and I thought it was fun, so I just kept doing it.

What is it that a sound designer really does?

Jessica: When we enter a Broadway space, all we get are our four walls. There's no cables, there's no speakers, there's no microphones. There is nothing. Everything that we bring in and customize in those four walls is the sound design.

When you're working on a show, do you find that it's a trickier equation when you're working in a smaller space?

Jessica: Interesting question. In theory, they're the same, right? Four walls, actors, a band. You provide a sound system that can cover the seating area so that each audience member is having as close to the same experience as possible. The principles of it are the same, the practice of it is a little bit different.

A show at a 300-seat theater will probably have a smaller budget than a show at a larger theater, and that affects the equipment you can order, so you have to prioritize.

And of course, the architecture of every theater is different; you can't just copy-paste. You have to choose the correct speakers for the space to avoid reflection off of certain architecture, like columns or support beams, so as to not throw a bunch of sound onto the walls that would then reflect into the audience and back onto the stage. The smaller the theater, the harder it is to hide things like that.

(© Emilio Madrid)

How closely do you collaborate with people like the music director and the orchestrator when you're working on a musical?

Jessica: Oh, constantly. They're my best friends in terms of feedback during the technical rehearsals. They let me know what instrumentation needs to be in the front of the mix, and what vocals need to be brought out versus held back when balancing microphones. There is constant communication between us.

When working on something like Hadestown, where the band is onstage, how do you ensure their sound isn't competing with the speakers, while still making sure audience members think all of the sound is coming from the right direction?

Jessica: For my money, the sound system has to be louder than whatever's coming off of the stage. The sound system has to win, otherwise someone who is sitting in the front row at the Walter Kerr is getting a different show than someone in the back row of the mezzanine. It is either an amplified show, or it's not; you can't really have it both ways. So yes, the band is on the stage, but you aren't actually hearing them from the stage; you're hearing them from the sound system.

What are some of the things that can go wrong during a show, once the system is set up?

Jessica: The simplest one is that people sweat. Sweat gets into their microphones and then they sound like they are under water. And also with microphones, cables may break because of choreography or just get strained or pulled or caught on something and it makes horrible sounds.

The technical fields in theater have long been considered something of a boys club – when you won the Tony Award for Best Sound Design for Hadestown, you were not only the first woman to win the award, but the first woman to ever be nominated. Did you experience any pushback against your entering the space?

Jessica: Here's what I'll say; no one ever specifically pushed back against me, but every opportunity I've been given in my entire career has been given to me by a man. They had to let me in the room. In many ways it has taken me four times as long to get to where I am. That's not any one particular person's fault, and I don't know for certain, but if I was a man, I feel I would have reached where I currently am in my career 10 years ago.

(© Monique Carboni)

Do you have any advice for women who are entering technical fields?

Jessica: For women specifically, a lot of them leave when they decide to have children, because this lifestyle isn't conducive to raising a family; that is a big part of the problem, because the hours are so long, and they are the opposite of the rest of society, so if you have a child to raise, it is extremely hard to balance everything. We work evenings, we work for 16 hours a day during tech, and if you're working the show itself, you're gone every night and every weekend.

This was something I wanted and it was something I wasn't willing to compromise on in any way. So I just kept showing up. I felt like if I stuck it out long enough, I'd eventually get what I wanted. And that has mostly worked out for me.

Other than that, you need to be curious, take on all of the work you can, and learn about how every other job operates. It's only going to make you a better collaborator. In terms of jobs like directing, designing lights, working in the wardrobe department, knowing how their jobs work will make you a better designer. If you're just starting out, learn how to program Q lab. Learn how to program Yamaha consoles and DiGiCo consoles. Learn how to use prediction software from various speaker manufacturers. Take every webinar you can to amass knowledge, and make sure to take notes. You never know when something will come up again years down the line.