5 Times Audience Behavior Was Worse Than It Is Right Now

Patrons may be bringing their phones to the theater, but at least they’re leaving the vegetables at home.

Between Patti LuPone's cellphone sleight of hand (and ensuing anti-phone-use crusade) and Hand to God guy's charger debacle, the theater community has managed to work itself into quite a tizzy over audience behavior. And while it may be true that the conduct of theatergoers has seen better days, with cargo shorts outnumbering tuxes and more candy-wrapper crinkling than seems possible, it's worth remembering that we've come a long way. At least Broadway theater lovers never have to worry about getting a tomato in the back of the head (except maybe at Something Rotten!).

1. Ancient Greece

While audible demonstrations of support, like clapping and cheering, are commonplace from today's audiences, it's becoming increasingly rare to hear a chorus of disapproving boos (unless you're Donald Trump). But there was a time when sharing your thoughts about a piece of theater, whether positive or negative, was thought to be a part of your civic duty. In ancient Greece, where jeering came of age simultaneously with theater itself, audience participation could mean the difference between life and death for participants in theater-related activities like the gladiatorial games.

Looks like you dodged a bullet there, Mr. Trump.

2. Dublin, 1747 (The Kelly Riots)

As we've recently been reminded, sometimes it's hard for college students to remember that rules regarding theater etiquette — especially the ones suggesting that the stage is off-limits — apply to them. So in 1747 Dublin, when guidelines that prohibited audiences from going onstage had only recently been instated, it was probably no surprise to see a drunken Trinity College student named Edward Kelly hop onto the boards at the Smock Alley Theatre. However, Kelly took his bad behavior one step further, making his way backstage to assault an actress — only to be punched by manager Thomas Sheridan.

Unfortunately, Sheridan's chivalry didn't put an end to the incident. The next night, Kelley and 50 of his best bros came back to the theater to teach the company a lesson, which they succeeded in doing by inciting a riot that tore up the interior of the theater. Too bad no one told Sheridan and Kelley about the value of a simple press conference.

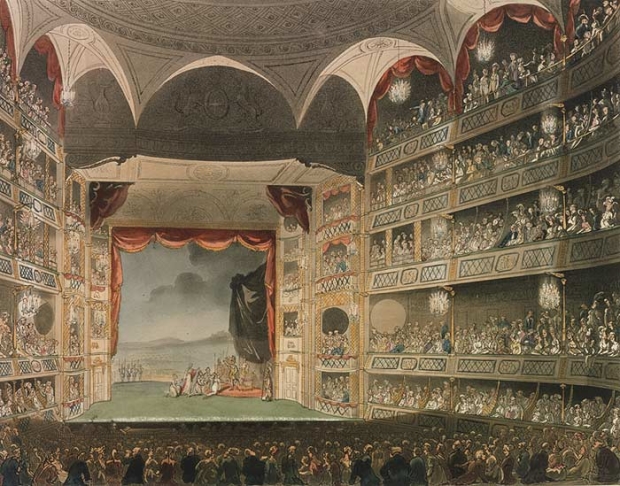

3. London, 1754 (The Drury Lane Theatre Riot)

Fortunately, jingoism is rarely the cause of bad behavior in the theater today. But in 1754, English audiences were less than open-minded about watching foreigners onstage — especially the French. When French balletmaster Jean-Georges Noverre brought his Chinese Festival dancing spectacle to London's Drury Lane Theatre only a short time before the two countries entered into the Seven Years War, audiences were vocally displeased. And when theater manager David Garrick refused to cancel the production, theatergoers began disrupting performances, eventually causing a riot that resulted in severe damage to the theater. If only Patti LuPone had been there to grab those swords right out of the rioters' hands, the whole kerfuffle could have been avoided.

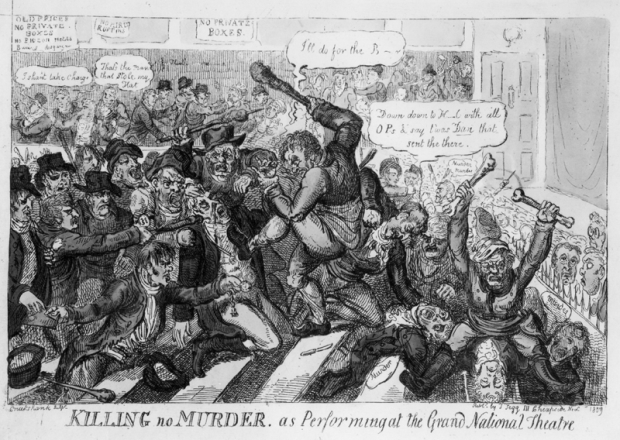

4. London, 1809 (The Old Price Riots)

No one likes it when the cost of their favorite commodities increase, but in the age of Comcast we've all learned to take price bumps in stride. However, in 1809, English theatergoers weren't quite so docile. When ticket prices at London's Covent Garden Theatre went up by a shilling to cover rebuilding costs following a fire, opening-night audiences responded by taking part in a little mid-Macbeth rioting.

Though theater manager John Philip Kemble tried to quell the disturbance with the help of police and even a squad of professional boxers, it wasn't until he agreed to bring prices back down — 64 days later — that the intermittent riots ended. Incidentally, beating up cash-strapped theater lovers did nothing for boxer Daniel Mendoza's popularity.

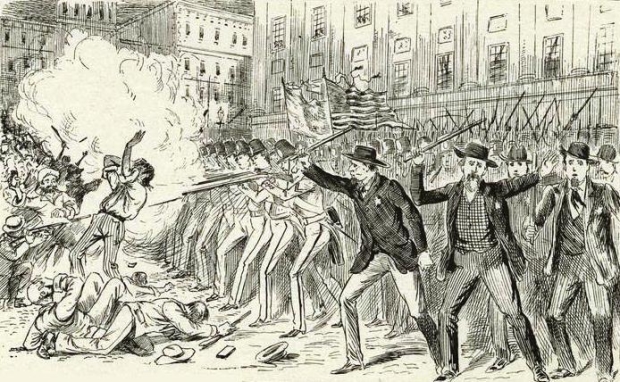

5. New York City, 1849 (The Astor Place Riot)

Probably the best-known instance of bad audience behavior at the theater is the 1849 Astor Place Riot. The disagreement, which ended up leading to a clash between a group of citizens and an armed police force, was over which performer, America's Edwin Forrest or England's William Charles Macready, was the better Shakespearean actor.

On May 7, three days before the riot itself, the two actors were both starring in Macbeth at New York City theaters only blocks apart and audience behavior was already at an all-time low. A contingent of Forrest fans had purchased tickets to the Macready performance at the Astor Place Theatre and proceeded to interrupt the show by throwing vegetables, eggs, and even their own seats at the stage. And by the time Macready was convinced to take the stage again, on May 10, anger had mounted even further, with thousands of enraged people filling the streets around the theater. The assembled crowds threw stones at the theater and engaged in scuffles with the police throughout the performance until finally the police opened fire on the crowd. The riot resulted in the deaths of dozens of civilians.

It's enough to make you thankful that the only injury we're in danger of in the era of in-theater cell phone use is a little auditory disruption and the wrath of our modern-day theater superstar Patti LuPone.

(© Joan Marcus)