A Beautifully Creepy Twelfth Night

The Acting Company and Resident Ensemble Players stage a chic revival of the top-shelf Shakespeare comedy.

(© Evan Krape / University of Delaware)

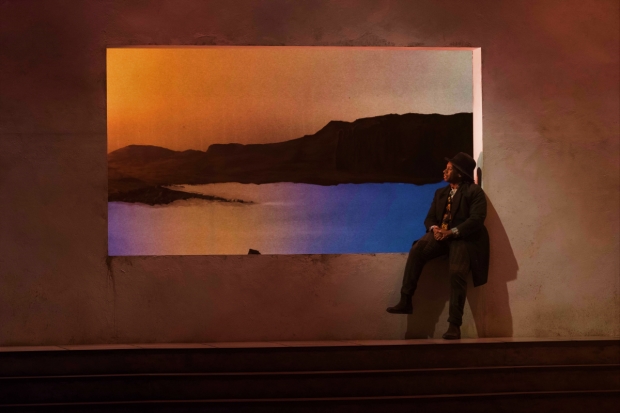

At first glance, Illyria looks like the kind of place you might want to retire: A picture window frames the arresting view of rocks rising out of the blue-green sea in the Acting Company's revival of Shakespeare's Twelfth Night at Polonsky Shakespeare Center (a coproduction with Resident Ensemble Players). But the longer we stare at Lee Savage's elegantly deteriorating courtyard set, the more we notice sinister undertones emanating from the heavy concrete walls and their conspicuous lack of windows. Is this a peaceful seaside villa or a fortress?

Suggesting the home of a drug dealer on a small Mediterranean island, Savage's set deftly evokes both glamour and terror. It's a smartly charged visual choice for a coastal territory occupied by both the bachelor Duke Orsino (Matthew Greer) and Olivia (Elizabeth Heflin), the mourning countess he thinks he loves. The situation is already fraught when Viola (Susanna Stahlmann) washes ashore, convinced that her twin brother (John Skelley) has drowned in a shipwreck. She disguises herself as the boy Cesario to gain access to the Duke, who employs his new page as an envoy to Olivia. Instead of facilitating the match between the two nobles, however, Cesario becomes the object of desire for both.

(© Evan Krape / University of Delaware)

Director Maria Aitken satisfyingly stages this love triangle, with the principal players delivering good (if not revelatory) performances. Heflin gives the most memorable turn of the night, playing Olivia with a fascinating mixture of authority and insecurity. The comic roles of Sir Toby Belch (Lee E. Ernst), Sir Andrew Auguecheek (Michael Gotch), Fabian (Mic Matarrese), and Maria (Kate Forbes) are, as always, more stimulating. Their epic practical joke on Olivia's steward, Malvolio (Stephen Pelinski), is the highlight of the play, with Pelinski marinating in aggrieved haughtiness. Joshua David Robinson is mischievous and slightly malevolent as the fool Feste, embodying the contradictory tones of this production more than anyone else.

It's a fitful synthesis, leading some of the comedy to feel awfully labored: We can spot a falling-undergarments bit from a mile away, so we barely chuckle when it arrives. Also, the decision to interpret the cleric Sir Topas as a charismatic southern preacher was surely funnier in the rehearsal room than it proves to be onstage.

(© Richard Termine)

Aitken approaches the design of the play with a much stronger hand: Candice Donnelly's outlandishly chic costumes are the real stars of the show. Poofy shoulders, tightly cinched waists, and hair teased to Jove make the stage regularly look like a photo shoot for Vogue Italia. This haute couture dazzles under Philip S. Rosenberg's lighting, which is bright enough to evoke a sun-soaked paradise, but targeted enough to reveal surprises in Savage's set. John Gromada's original music walks the line between hipster whimsy and horror, reimagining Feste's numbers as atonal art songs (all impressively interpreted by Robinson). Everything comes together in a picture of aggressive fun that could turn dark at any moment, like partying with Michael Alig at the Limelight.

This is not the way we typically think of Twelfth Night, a holiday romp of gender-bending mistaken identity with a happy ending. Still, Aitken convincingly identifies the danger lurking beneath this seemingly fanciful tale of erratic nobles looking for love: Should things go slightly differently, heads would roll. Aitken never lets us forget the violent authoritarian power that undergirds this story, tying the comedy to real stakes. If she could make that comedy actually funny, this production would really be something.