(© Joan Marcus)

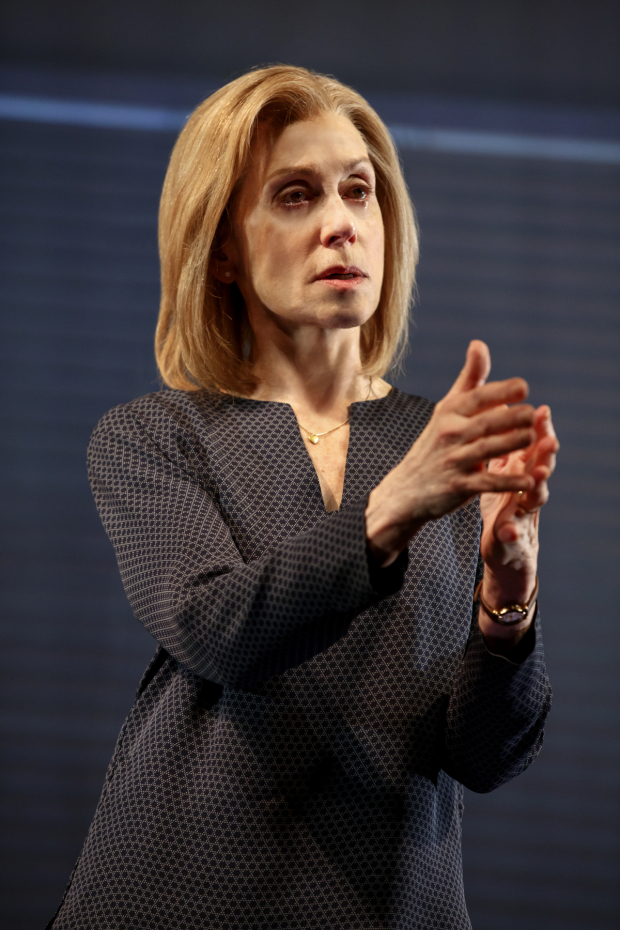

One of the greatest stage actresses in New York is starring in a world premiere by one of our most celebrated playwrights. That would be Neil LaBute's All the Ways to Say I Love You from MCC at the Lucille Lortel Theatre. It's a solo show featuring two-time Tony winner Judith Light (The Assembled Parties) as a sexually frustrated high school English teacher (perfunctory burgundy cardigan courtesy of costume designer Emily Rebholz). With direction by Tony nominee Leigh Silverman (Violet), it is a disappointing misfire from an otherwise dynamite team.

LaBute is one of America's foremost dramatists, having built a reputation for searing dialogue and unexpected plot twists in plays like The Shape of Things, Reasons to Be Pretty, and Reasons to Be Happy (the latter two also premiered with MCC at the Lortel). LaBute continues his penchant for the unexpected by eschewing all that makes him a thrilling writer, penning a play that is limp in both story and language. After its elaborate windup, All the Ways to Say I Love You feels like a noncommittal tap on the shoulder rather than a sock to the gut.

(© Joan Marcus)

Mrs. Johnson (Light) is in a loving but sexually unsatisfying marriage with her husband, Eric. She finds an outlet for her pent-up lust in Tommy, a student repeating his senior year. The sex is apparently mind-blowing and Mrs. Johnson lets us know that she never regrets it, but does she regret betraying her husband? That question is more difficult to answer as Mrs. Johnson spends an hour delivering this confessional monologue that is part seminar and part deposition.

Such a story immediately conjures memories of Mary Kay Letourneau, the middle school teacher who went to prison in 1998 for having an affair with her 12-year-old student (they married upon her release and are still together today, unlike many of the other couples that vied for tabloid headlines alongside them). Granted, the stakes in LaBute's play are significantly lower than this real-world drama: Since Tommy is repeating his senior year, it is clear that everyone in this story is a consenting adult. There will be no jail time for our heroine. On top of that, the story lethargically meanders as LaBute drops little breadcrumbs that encourage us to hold out hope for an exciting twist that never really comes: We are told several times that Eric is biracial and Tommy is black, suggesting that LaBute wanted to say something about this, but never really does.

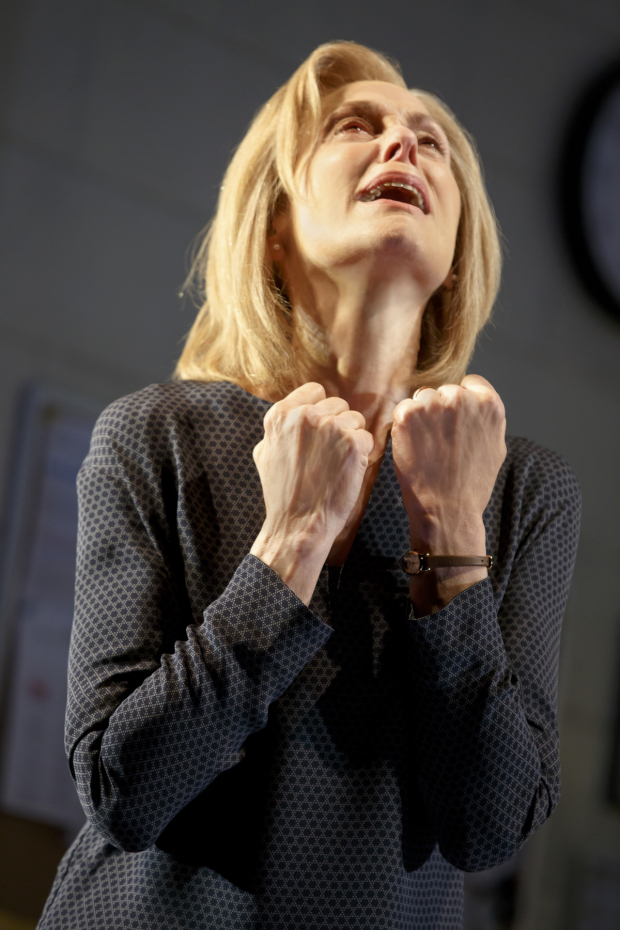

Light compensates for the lack of urgency in the text by manufacturing her own. She repeats key phrases in a dark tone à la Charles Busch: "The truth…in the end, might surprise us all…even me," she says, staring gravely out at the house for a beat, "Yes, even me." In recalling the passionate nights she shared with Tommy, she begins to tremor in a full-body flashback. Certain phrases have the power to make her spontaneously burst into tears: It's a jarring choice, but the dramatic returns diminish each time Light employs the trick. Sure, it's fun to hear her enunciate "Baby Gap" and "Pottery Barn" as if she were playing Medea, but it transforms the piece into camp in a way that LaBute likely did not intend. It also keeps us acutely aware of the falseness of the script: We're never fully able to suspend our disbelief.

(© Joan Marcus)

Director Silverman (who helmed LaBute's The Way We Get By last season at Second Stage) does little to solve the disconnect between text and performer. She mostly blocks Light downstage, leaving her to pace from one end of the constructive proscenium to the other, like a nervous cougar in the Central Park Zoo. Scenic designer Rachel Hauck has crafted a believable teacher's terrarium: Mrs. Johnson's messy metal desk sits in front of a painted cinder-block wall. Institutional windows face upstage, masked (crucially) by large view-obscuring blinds. Lighting designer Matt Frey has some fun with these, allowing a sickly green light to seep in from behind as Mrs. Johnson reaches the climax of her story. Sound designer Bart Fasbender chimes in with a whirring note that, like an aural highlighter, signals tension in a way the script never does on its own.

Were LaBute to revisit the text and inject a little danger, All the Ways to Say I Love You might work as a pretty good short story, the kind with an unreliable but erudite narrator who helps us to imagine the lurid details of her affair. As it is, this solo show comes across as an abandonment of the most potent tools (dialogue, action, suspense) at a playwright's disposal.