Arthur Miller's The Crucible.

The Salem witch trials crash the PTA in this Broadway revival of an Arthur Miller classic.

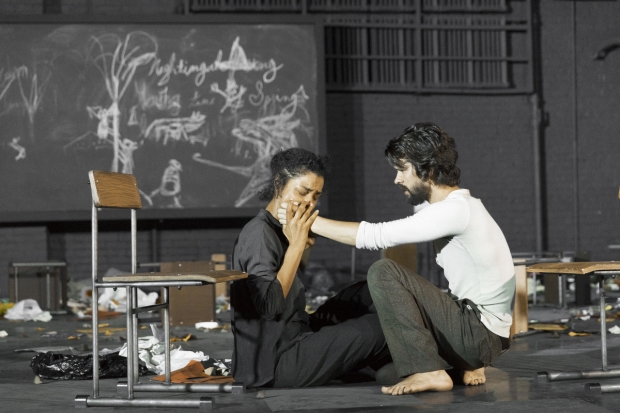

(© Jan Versweyveld)

The puritans serve coffee from a large thermos, bracing for what promises to be a highly combustible school board meeting. At least, that's what it looks like they're preparing at the Walter Kerr Theatre, where director Ivo van Hove has mounted the highly anticipated Broadway revival of Arthur Miller's The Crucible. It's a visually striking production, laden with dynamite performances. Sure, the conceit might be a little on the nose, but when was this didactic drama ever subtle?

The play debuted on Broadway in 1953, at the height of Senator Joseph McCarthy's crusade to root out Communists from American public life. Never one for nuance, Miller attacked McCarthyism by writing a play about an actual witch hunt: the Salem trials of 1692. Audiences got the message: "I stood in the back of that theater after opening night and I saw people come by me whom I'd known for years — and wouldn't say hello to me," Miller recounted in an interview with Matthew C. Roudane of the Michigan Quarterly Review. No one wanted to risk guilt by association, thereby proving Miller's point.

Of course, McCarthy was eventually censured by his Senate colleagues for his excesses, dying in disrepute in 1957. The Crucible has since been hailed as a modern masterpiece, spawning productions across the country and a Broadway revival nearly every decade (the 1980s being the only exception). The play's explosive mix of sex, religion, and politics helps explain its continued resonance.

(© Jan Versweyveld)

It opens with Reverend Parris (Jason Butler Harner) fretting over his sick daughter Betty (Elizabeth Teeter). The doctor suspects her affliction is unnatural. Betty was recently seen dancing in the woods with her cousin Abigail Williams (Saoirse Ronan) and several other girls; rumors of witchcraft circulate. Parris summons demonology expert Rev. Hale (a scholarly and judicious Bill Camp) to examine Betty. Abigail decides to turn the rumors around on her enemies, specifically her former employer Elizabeth Proctor (Sophie Okonedo). Abigail had a brief affair with Elizabeth's husband, John (Ben Whishaw), leading to her dismissal. As accusations spiral out of control, Judge Hathorne (Teagle F. Bougere) and Deputy Governor Danforth (an appropriately intimidating Ciarán Hinds) arrive in Salem to preside over the subsequent trials. The accused face a difficult decision: Confess to consorting with the devil, or hang.

While Miller sought to thinly veil his critique of contemporary America in a 17th-century costume drama, van Hove (fresh off the acclaimed revival of Miller's A View From the Bridge) does the opposite, firmly placing his production here and now. Not only that, he sets it in the place a certain class of Americans is most likely to feel persecuted by the inquisition: high school. Certainly, the continued book-banning and fraught debates over student clubs are enough to justify this choice.

Scenic designer Jan Versweyveld places the action in an open institutional room that appears to have been constructed in the 1930s. Massive radiators and a blackboard dominate the upstage wall, which is covered in a few too many coats of blue paint. A stage-left modern glass partition suggests recent renovations.

Wojciech Dziedzic's adult costumes seem inspired by the Land's End catalogue: conservative slacks and pilled sweaters. The wealthy Putnams (a believably snooty Tina Benko and Thomas Jay Ryan) are naturally dressed a cut above everyone else. The girls, meanwhile, wear school uniforms.

(© Jan Versweyveld)

Taking her cue from this aesthetic, Ronan (a recent Oscar nominee for Brooklyn) plays Abigail like the Regina George of Salem High. "I will come to you in the black of some terrible night and I will bring a pointy reckoning that will shudder you," she threatens the other girls in a vengeful rasp, and we absolutely believe her. When she embraces Mary Warren (Tavi Gevinson, artfully crafting a clear journey for her conflicted character) in a group hug, we cannot help but gasp at the transparency of it all.

Composer Philip Glass (who also scored the delightfully melodramatic student-teacher-affair film Notes on a Scandal) employs a conspiratorial cello to underscore Abigail's interactions with John Proctor, sending shivers down our spines. But if the music brands her a seductress, her adolescent uniform never lets us forget the adult in this situation.

For his part, the scruffy and handsome Whishaw plays a likable lecher. His moments with Okonedo are tender, conveying a marriage of many years, with all its accompanying baggage and complications. Okonedo, in her first Broadway turn since winning a Tony for A Raisin in the Sun, embodies an Elizabeth who may come off as cold, but for whom it is hard to conclude, as she does, that this is what prompted John's adultery. The truth of the matter remains shrouded in Miller's text, never fully revealed by the director's seemingly tidy staging.

(© Jan Versweyveld)

Van Hove is the master of visually arresting moments: The alarming third-act opening will have audience members clinging to their seats, eyes glued to the stage. That same act concludes with a gale force. Unfortunately, the beats between these set pieces often seem neglected. When the director does intercede, it regularly comes off as stagey, as when the advisers of the court vigorously circle Danforth, like flies on rotting fruit.

This may be van Hove's way of dressing up Miller's overwrought dialogue and uneconomical plot development, which causes even the strongest mountings of this play to sag. This is the best production of The Crucible I've ever seen. It is by no means a perfect drama, but as long as a crusading morality is a part of our national character, it seems destined to continue punching audiences in the gut.