Briefly, Peace on Earth in All Is Calm: The Christmas Truce of 1914

A World War I play with music from Minneapolis’s Theater Latté Da arrives at New York’s Sheen Center.

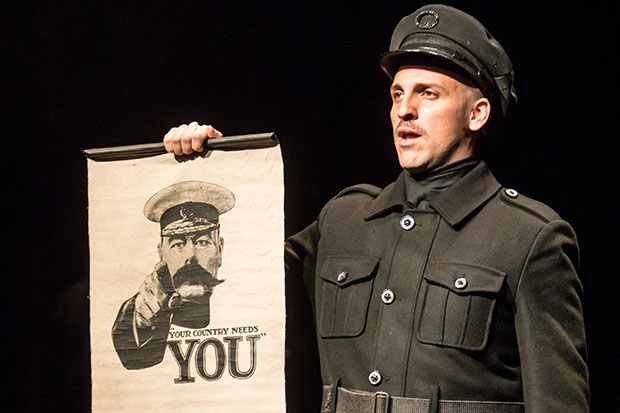

(© Dan Norman Photography)

Last week, leaders from across Europe gathered in Paris to commemorate a century since the armistice that ended the First World War. Could that centenary have occurred four years earlier, in 2014? All Is Calm: The Christmas Truce of 1914 recalls an event that seemed to hold out the promise that the fighting would stop just five months after it began. Through song and the actual words of the men who were there, writer-director Peter Rothstein re-creates that incredible moment of hope — one that would eventually cede to violence. It is, hands down, the most emotionally moving Christmas show I've ever seen.

The Christmas truce was a spontaneous cessation of hostilities along the western front, and it really happened. Regular British and German soldiers (the latter before the former) climbed out of their trenches and met in no-man's-land to exchange gifts and good cheer. For just one day, the dying class went on strike; and everyone wondered if it would last.

(© Dan Norman Photography)

Rothstein has drawn his text from firsthand accounts from the men who were there. We follow them from ecstatic enlistment at home to anxious arrival at the front to torment in the trenches. "I thought it would be nice to be with a lot of lads on something of a picnic," says a Highland soldier recalling the misplaced optimism of the summer, "because we all thought the war would be over by Christmas."

Erick Lichte and Timothy C. Takach's gorgeous a cappella arrangements of popular songs like "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" and "Keep the Home-Fires Burning" underscore these testimonies in multipart harmony, making the play feel like a live Ken Burns documentary. Christmas carols in English, French, and German arrive in the latter half of the show, often overlapping and interweaving with one another. There isn't a minute in this tight 75 without music, and Lichte (who also serves as music director) has led the 10-man cast to a quality of sound rarely heard outside of a concert hall.

(© Dan Norman Photography)

Rothstein stages it all with cinematic fluidity, so that one scene fades seamlessly into the next. Trevor Bowen's all-black costumes are individualized for each cast member, while also allowing them to instantly transform from one character to the next (there are 39 in total): An actor slips on a German helmet and, suddenly, he is in the opposite trench. Marcus Dillard's subtle yet effective lighting highlights the speaker downstage while distinguishing between night and day. The performers never stop moving and singing throughout.

It is a testament to the cohesion of Rothstein's production that no individual performers stand out. This is a true ensemble piece, and each actor has the ability to embody a multitude of soldiers on both sides (dialect coach Keely Wolter impressively manages to convey not just nation, but region and class). We feel like we're actually hearing their voices broadcast through time, and we're grateful for the opportunity to listen. It's hard not to get choked up with performances as honest and unvarnished as these.

(© Dan Norman Photography)

All Is Calm doesn't earn its tears through blind sentiment. It doesn't shirk the fact that the truce was not repeated in the subsequent Christmases of 1915, 1916, or 1917, as poison gas smothered whatever good will remained across enemy lines. Nor does it oversell the potential of this brief, illicit fraternization to end the war. But it does suggest that onto that muddy patch of land, the first step toward a common future was bravely made — not by the great men of Europe, but by the little guys, whose posterity should be eternally grateful.