Children of a Lesser God Challenges Broadway to Really Listen

Joshua Jackson and Lauren Ridloff star in the Broadway revival of Mark Medoff’s 1980 Tony-winning drama.

(© Matthew Murphy)

The first Broadway revival of a play usually offers a clear indication of whether the piece has staying power. Not so with Mark Medoff's Children of a Lesser God, now playing at Studio 54. The 1980 Tony winner for Best Play, Children returns in a production directed by Kenny Leon (the 2014 revival of A Raisin in the Sun) and starring Joshua Jackson (forever of Dawson's Creek) and former Miss Deaf America Lauren Ridloff. Exciting performances infuse Medoff's musty script with new vitality, but Leon regularly undercuts his own hard work with a production that seems intent on pulling the play into the memory hole of time.

Jackson plays James Leeds, a speech teacher at a school for the deaf in the late 1970s. He works mostly with students who retain some residual hearing, like Orin (John McGinty) and Lydia (Treshelle Edmond). But former student and current maid Sarah Norman (Ridloff) was born completely deaf and has no idea what speech sounds like. James insists to head teacher Mr. Franklin (a pompous Anthony Edwards) that he can teach Sarah to talk. He never considers the possibility that she's not interested in struggling to speak when she can communicate perfectly well through American Sign Language (ASL). This becomes a problem when their relationship crosses the threshold of what is appropriate between a student and a teacher.

(© Matthew Murphy)

Leon does a good job navigating the potentially perilous sexual politics of this play, and much of this has to do with Ridloff's self-assured performance. Despite the obvious power imbalances between them, we never doubt that Sarah consents to her relationship with James. In fact, she seems to be the one in the driver's seat.

Ridloff confidently steps into the role that won Phyllis Frelich a Tony Award in 1980 and Marlee Matlin an Academy Award in 1987. While Matlin conveyed Sarah's fury by assaulting the air with her sign, Ridloff opts for a posture that is simultaneously cooler and more cynical. Her caustic gaze is withering, enough to send Lydia fleeing to the wings. At the same time, her tenderness with James causes us to look askance when he declares that she is "the most mysterious, attractive, angry person I've ever met." Is she "mysterious" because she is deaf? Is she "angry" because she is black? Is she "attractive" because that's what really matters to him? Ridloff's performance makes us consider the narratives we assign to the people around us, which often have little to do with their actual behavior.

Why is this? It would be hard to claim that James isn't paying attention, since a significant percentage of his lines involve him repeating Sarah's lines for the benefit of the hearing audience, including when they are alone.

Leon miraculously mitigates the momentum-killing impact of this authorial contrivance by having Jackson perform Ridloff's lines like a local anchor reporting the 11 o'clock news. A speech teacher who is always on, his diction is loud, clear, and presentational. He also executes his southpaw ASL with seasoned grace (Leon smartly blocks him stage left of Ridloff for their most significant exchanges). It feels like a revelation when his professional, vaguely comic armor finally comes down. It's almost as jarring as the cathartic moment when Ridloff finally uses her voice after remaining silent for the previous two hours and 30 minutes. In both instances, it is clear that James and Sarah are finally, truly listening to each other.

(© Matthew Murphy)

We get surprisingly full glimpses of the other characters too, considering this is a world composed entirely of James's memories: As Sarah's mother, Kecia Lewis exudes the hardened skepticism of a woman who has followed the advice of medical "professionals," and then shouldered the blame when that advice backfired. McGinty delivers a forceful interpretation of Orin, a would-be revolutionary whose deliberate physicality and sharp diction could easily rally the people to the barricades.

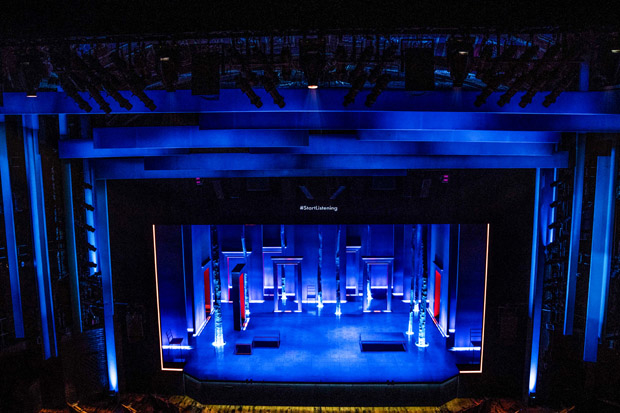

Unfortunately, they share the stage with a bizarre production design. This memory play takes place inside James's head, which set designer Derek McLane imagines to look like Christmas at the Trumps'. Lighting designer Mike Baldassari illuminates this forest of dead trees and door frames from underneath, casting everything in a sinister glow. Dede Ayite's late '70s costumes and Jill B.C. Du Boff's funky sound design tether us to time and place in this cold alien landscape (the former doing a much better job than the latter). Branford Marsalis's generic original music also does this, albeit in more embarrassing ways: Tinny synth ditties practically scream '80s melodrama, while a mischievous clarinet and dramatic violins combine to make it all feel a bit too close to camp for the revival of an allegedly serious drama.

(© Matthew Murphy)

Between excellent acting and mediocre design, the former wins out, but just barely. I'm still not convinced that Children of a Lesser God is durable enough to remain in the theatrical repertory: Medoff's language is too clunky and his drama too contrived. Still, that shouldn't prevent us from connecting with these very human performances for a fleeting moment — which Medoff suggests is all we usually have.