Credits, or Credibility?

With everyone hungry for the security of big names, does art stand a chance?

(© Evgenia Eliseeva)

I stumbled over a parenthetical the other day. It was in a press release, the kind that floods into my email inbox as they do into every theater journalist's. All theaters, particularly small ones, are desperate for publicity, and sometimes even deserve it.

This particular harmless-looking press release was inviting us to a new play written and directed by a young woman I'll call Ms. X. Good for her: By hook or by crook, she got her play on. What made me stumble, though, was the parenthesis that followed her name, right there in the lead sentence: a pair of curved brackets enclosing the title of a fairly successful show that had run a longish time in New York — a show, as I knew perfectly well, that Ms. X had neither written nor directed.

Naturally, I checked. It turned out that Ms. X had been a late replacement in the show's New York cast, playing the last few months of its long run. So her press release told no lie; she had the right, in some sense, to claim this credit.

Still, that little parenthesis set me thinking. If its placement at the top of the release wasn't meant to imply that the writer and director of this new play had been involved in the writing and direction of that long-run hit, then just what was it meant to imply — that she had professional credits? Fine, I suppose. That she glittered from the luster of association with a hit? Well, sort of. But what did any of that say about her ability to write or direct? Was she being mentored by the hit show's creators? The bare parenthesis said nothing about that. For all I knew, she might never have even met them — replacements get put into a show by the stage manager and the assistant director; it's a big day for them if the author or director merely drops by to say "Break a leg," or "Speed up that second-act exit." And if the credit in parentheses said nothing about mentoring, or creative input, was it saying anything at all?

My complaint may seem like an absurdly tiny piece of nit-picking, but it's actually not. All modes of communication, including press releases, reveal the communicator's view of the world. They may not shape our understanding of the theater, or of life, but they seep unbidden into our ongoing dialogue about it. And from us — from our live conversations, online chats, Twitter feeds, news items, feature stories, and reviews — they seep into the public mind. So you might say that to read what a show's press rep has put into the release is an indirect way of taking the public's pulse: This is what a publicist believes will encourage people to attend this particular show.

(© Joan Marcus)

Judging from the releases that flock to join that of Ms. X in my inbox, the theater public's pulse just now is moving sluggishly at best. The outside world is changing with manic speed, our theater lurches this way and that struggling to maintain its balance while keeping up with the world. Meantime, the economic demands of the business — always worse in New York than anywhere else — have driven ticket prices to a lunatic high in all but the smallest and most modest venues.

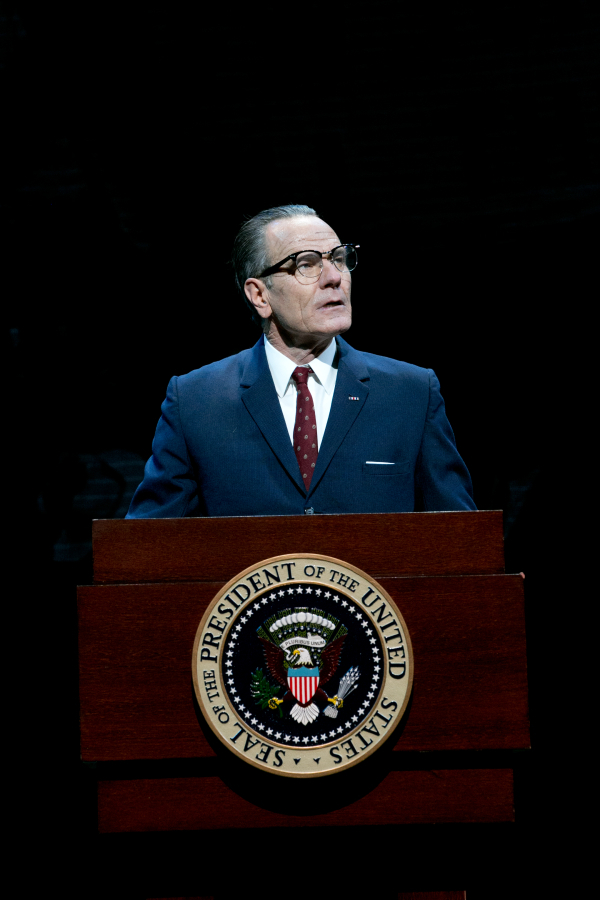

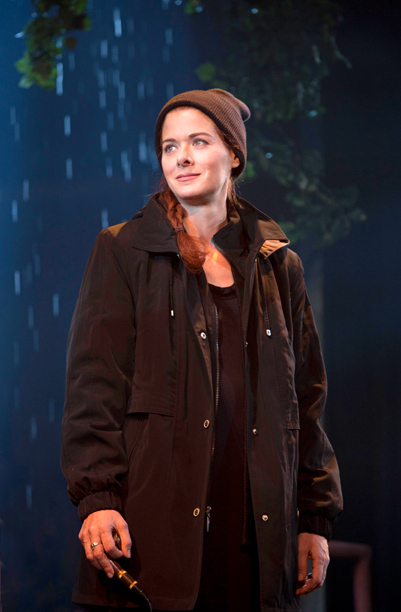

In such a time, when the public is watching its pocketbook and wary of risk, familiar names become sacred totems: Broadway shows now mean shows with stars; new musicals mean the most fondly remembered movies of the recent past recycled; revivals get chosen from an ever-shorter list of plays and musicals that have previously proved their box-office worth multiple times. In that atmosphere, the willingness of a Bryan Cranston to tackle a long and arduous role in a serious, large-scale new play like All the Way becomes a welcome surprise. (This year, bankable male stars on Broadway have opted for familiar titles; other than Cranston, it's mostly female stars sustaining Broadway's new-play tradition: Debra Messing in Outside Mullingar, Tyne Daly in Mothers and Sons, Toni Collette in The Realistic Joneses, Estelle Parsons in The Velocity of Autumn.)

Producers' caution, like that of the ticket buyers, is understandable. More than ever these days, the theater is both a costly and an unreliable enterprise. Artists who expect to make a viable living solely from the stage are pursuing an idle dream; commercial producers, however cagey, who fantasize reaping epic profits from it may be the victims of an even greater delusion. The giant entertainment conglomerates, with their octopus-like multitudes of arms busily perpetrating mediocrity in multiple media, can readily write off even a fairly large Broadway thud like a Tarzan or a Lestat, its loss quietly absorbed in the shuffling of huge sums from one subsidiary to another. Few individual producers have such deep and easily rearrangeable pockets. Consequently, when the cost of risk runs high, theater becomes more corporate — meaning that by definition it becomes drearier, less spontaneous, soggier with test-marketed predictability. The Surpreme Court notwithstanding, corporations aren't people. A person, even a theatrical producer, can dream; corporate dreams are always sterile. But I'll have more to say about dreamers and marketers, credits and credibility, next week.

(© Joan Marcus)

Stay tuned to TheaterMania for part II of this "Thinking About Theater" column, which will appear on Friday, April 25.