Dominique Morisseau's Rules of Engagement

The playwright reveals the inspirations of her two new projects, Lincoln Center Theater’s ”Pipeline” and Berkeley Rep’s ”Ain’t Too Proud”.

(© Tricia Baron)

"My husband always says to me, 'We think we know about school because we've all been to school, but we really don't have a clue about what goes on there," says playwright Dominique Morisseau.

Unless you're a teacher.

But Morisseau, whose works include Sunset Baby, Detroit '67, and Skeleton Crew, does know. Not only is she the daughter of a now-retired public school teacher (who spent 40 years as an educator in Highland Park, Michigan), but she herself has also spent time teaching in the classroom, both in her native Detroit and New York City. Morisseau has taught at schools in all five boroughs, including Evander Childs in the Bronx and August Martin in Jamaica, Queens.

Through her experiences in what she calls "the insular world of being an educator and teacher in public schools," Morisseau has created her latest play, Pipeline, at Lincoln Center Theater's Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater. It's the story of Omari, a young African-American man facing expulsion from his upstate private school after a violent incident on a bad day; and his mother, Nya, an inner-city public school teacher must examine her own desire to give her son the opportunities her own students could never afford.

The story, she says, is a personal one. "I'm interested in all the ways education in this country impacts young people's ability to have a fair shot in the world. The horrible trend of young black men being killed by police, and recently reading Michelle Alexander's book The New Jim Crow, which looks at mass incarceration in this age of color blindness, as she calls it, made me interested in the school-to-prison pipeline."

(© Jeremy Daniel)

It's a subject that is not frequently discussed on the stages of New York City, let alone anywhere else (the subject was also addressed in Anna Deavere Smith's recent solo show, Notes From the Field). "Knowing what it's like for a teacher is a hard world to fully imagine," Morisseau continues, noting that fictional television and written depictions of life as a teacher don't do it justice. "You don't know war unless you go into war."

Young men that Morisseau has encountered, "a few very personal stories in my life," inspired the character of Omari. But in a more general sense, the inspiration came from stories of young male students "who had really bad days and really bad moments, and how quickly those moments became an act of criminalization of that young kid. It's scary how fast that can happen."

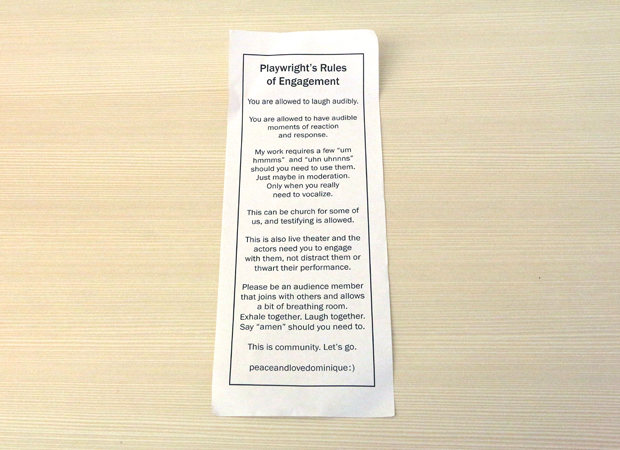

Pipeline is a play that calls for responses from its audience members, and Morisseau is proud to make that clear. Every program distributed before the show comes with a leaflet titled "Playwright's Rules of Engagement," which includes such dictums as "You are allowed to laugh audibly" and "You are allowed to have audible moments of reaction and response."

(© David Gordon)

Morisseau takes a breath when describing the pamphlet. "My shows that have been programmed at theaters across the country have predominantly white audiences in their subscriber base. I have seen the sprinkle of audience members of color who have a conflict of engagement with those white audiences. Or maybe, those white audiences have a conflict of engagement with those audiences of color. There are moments I've noticed, repeatedly, where the people of color think they are guests in the space. They hush as though they've broken the rule of the space, instead of engaging with my work the way I think my work demands, which is with a little bit of an audible response." Morisseau's written encouragement of interaction allows all audiences to realize that it's OK to be vocal, and that theater is a communal activity. "What I've asked for is space for the community to respond to my work."

While Pipeline previews at Lincoln Center, Morisseau is dividing her time between Manhattan and California, where she's working at her day job, as coproducer on the Showtime series Shameless. Working on a series has taught her new facets of writing. She considers herself a "very dense writer," the denseness filled with "rhythm and musicality." On television, she needs to be sparse. "I have to find a different kind of poetry to make the characters speak in."

This training helped with her other major theatrical project: Ain't Too Proud, a musical that explores the rise of the Motown supergroup the Temptations. It's Morisseau's first time writing the book for a musical, but it wasn't as challenging as she expected it to be, even though the songs were both already written and a part of music history.

"I thought it would be like I didn't know what I was doing," she says with a laugh. "I really worked hard to not make it a typical jukebox musical. It is very integrated into the storytelling and function of the show." Running August 31-October 8 at Berkeley Repertory Theatre, the production begins rehearsals the day after Pipeline opens.

It's a shift in gears, naturally, but one that Morisseau embraces. "I love the collaboration of a musical, which is so different than the collaboration of a straight play." But ultimately, it's all about the truth. "Mustering the courage to be truthful is what's hard for me in a lot of ways," she says. "People get hurt by the truth." But no matter the style of storytelling, whether you're working on a bio-musical, a play, or a television script, you must embrace the truth. And for Morisseau, with that truth comes the power to engage an audience in stories we very much need to hear.

(© Chasi Annexy)