Fade

Tanya Saracho’s new play follows the relationship between two Mexican-Americans living in Los Angeles.

(© James Leynse)

Mexicans are as homogeneous as Americans — that is to say, not very. Tanya Saracho explores this obvious but little-discussed (at least north of the border) truth in Fade, now making its New York debut with Primary Stages at the Cherry Lane Theatre. This tale of two Mexicans is a multilayered and incisive look at the internal dynamics of a group often viewed as a monolith within the larger culture. It is undeniably relevant in 2017.

Saracho, who has written for Girls, Looking, and How to Get Away With Murder, sets her story in familiar territory: Novelist Lucia (Annie Dow) has relocated to Los Angeles from Chicago to take a job as a television writer. She's the only young Latina in a writer's room full of older white men, and she feels it. Upon moving into her office, she accidentally breaks the shelves behind her desk and asks Abel (Eddie Martinez), a member of the maintenance crew, to fix it. Assuming that he doesn't speak English well, Lucia speaks to him in Spanish, even though he was born in East L.A. and speaks with an American accent. "Me assuming you speak Spanish wasn't like an insult," she tries to explain. "It's a little like, 'We're in this together' when I do it, you know what I mean?" But Abel looks askance at her assumed "we."

(© James Leynse)

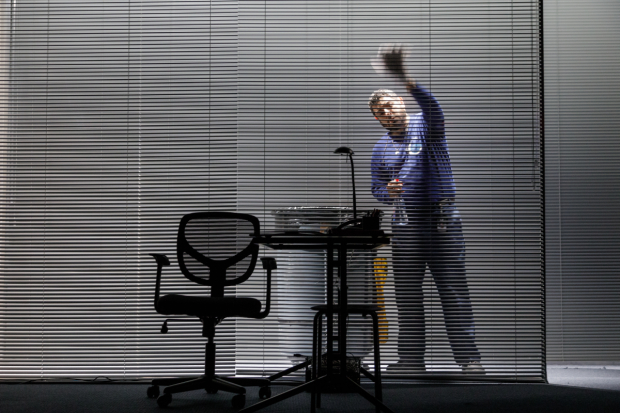

While Lucia and Abel check the same box on the census form, they lead very different lives: She works in her own private office; he cleans the glass walls. A "Semper Fi" tattoo on his left forearm comes into view when he reaches for her trash. Over the course of 90 minutes, their differences come to the fore as Lucia uses Abel's life as inspiration for her writing, resulting in some major career advances. When so much of the American discussion of privilege focuses on race, Saracho bravely writes about class, a trait that might just be a more decisive factor in one's placement in the pecking order.

Shrewdly, Saracho and director Jerry Ruiz muddy the waters to prevent any easy conclusions: Abel is also just a little browner than Lucia, who speaks with a Chicago accent and could easily pass as a gringa. This is despite the fact that, unlike ex-Marine Abel, Lucia was actually born in Mexico, albeit to a very well-off family: "You know everyone in Mexico has a maid, it doesn’t make you a fresa," she matter-of-factly tells Abel, using the Mexican slang term for "bourgeois." The competing forces of ethnicity, nationality, gender, and wealth grapple onstage like combatants in a Lucha battle royale.

(© James Leynse)

While wonderfully evident in her characters, Saracho's impulse to complicate rarely translates to her dramatic situations, leading to some confusing and all-too-easy moments: At one point, Lucia mopes about her role in getting a coworker who called her "the diversity hire" fired. How did she do it? By offering to work on the weekends when he would not. File this conflict under guilt-free karma. In an effort to make Abel more sympathetic, Saracho has also left some major holes in his backstory.

Luckily, Ruiz's well-staged production helps us suspend our disbelief over these storytelling chasms. His staging is tight and efficient without smothering the performances of the two actors.

Dow is eerily authentic as the high-strung writer suffering from self-inflicted stress. She holds her tension in her shoulders and regularly cuts Abel off when she has something to say. The disdain she has for her new job occasionally escapes in the form of a harsh Chicago vowel, which she clings to as if it were a buoy, keeping her from drowning in the ocean of artificiality that is Los Angeles.

Martinez marches with determination through the narrow hallway behind Lucia's office, a man clearly accustomed to executing his tasks with maximum efficiency. Where she is prone to overshare, he remains guarded until late in the play, as if he intuitively senses the danger of consorting with someone like her. His reserved and heartfelt performance helps infuse the play with an unspoken tension.

Costume designer Carisa Kelly subtly charts Lucia's transformation: After her first dust-up with Abel, she wears a long skirt and brightly colored bead earrings, telegraphing her Mexican bona fides. By the end of the play, she wears a little black dress and a chunky gold necklace: the armor of an L.A. power player. Set designer Mariana Sanchez perfectly captures the soulless sterility of Lucia's glass and gray office, and Amith Chandrashaker uses the indigenous lighting of that office to accentuate the mood of each scene. Sound designer M.L. Dogg underscores the blackouts between Saracho's short, cinematic scenes with Mexican pop music, helping to ease the transitions.

(© James Leynse)

Saracho has written a provocative play that asks its audience to reconsider its own place in a country where everyone is allegedly "middle-class." How do our different starting positions affect where we end up? When does representation cross the line into exploitation? When is it a privilege to even have the opportunity to "lean in" and seize the power others would deny you? Saracho's teeming intelligence and emotional sensitivity more than compensates for the occasionally awkward contrivance of her script, making Fade a worthwhile night at the theater.