Fires in the Mirror Exposes Segregated New York City

Anna Deavere Smith’s theatrical documentary returns nearly three decades after the original incidents that inspired it.

(© Joan Marcus)

New York is a segregated city. Of course, northerners don't like to think about their metropoles that way. Chicago and Milwaukee never suffered under Jim Crow, yet a recent study named the latter the most segregated city in America (NYC was second, Chicago third). How could this be?

Anna Deavere Smith explored the causes of urban segregation, and its deadly costs, in Fires in the Mirror, a documentary play about the three-day 1991 race riot between the Lubavitch Orthodox Jewish and black communities in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Smith based her script entirely on interviews she conducted with members of those communities, performing them verbatim. It gave the play a ripped-from-the-headlines quality when Smith performed it at the Public Theater in 1992 (and when it aired on PBS in 1993). But does this "relevant" theater have the same impact when it is performed 27 years later, by an entirely different actor?

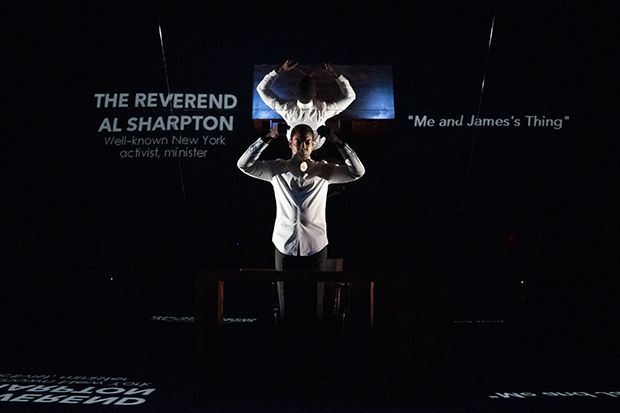

(© Joan Marcus)

This Signature Theatre revival starring Michael Benjamin Washington proves that it does. Washington plays 25 characters who either witnessed the Crown Heights riot or have something to say about it. There's Rabbi Joseph Spielman, who insists that when the motorcade for the Grand Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson struck and killed 7-year-old Gavin Cato (a black child of Guyanese descent), three city ambulances responded before the private Jewish volunteer Hatzolah ambulance arrived. There's the Reverend Heron Sam, who counters that the Hatzolah was the first on the scene, and it completely ignored the black children under the rebbe's car in favor of its Jewish occupants. And then there's Norman Rosenbaum, who flies from Australia to demand justice for his brother Yankel, who was murdered hours after the collision by a mob allegedly shouting "kill all Jews."

Fires in the Mirror vividly exposes the fault lines in our society, a supposed melting pot in which the constituent ingredients refuse to melt. "They all stick together like glue," an anonymous black teenager says about three Dominican girls in her class. When kids learn how to segregate by nationality from an early age, what hope is there for adults? Fires in the Mirror still shocks all these years later as the thoughts of poor and brown New Yorkers are given a hearing in front of a mostly well-to-do white audience who would otherwise never stop to listen.

This is remarkable considering Smith has left her script largely intact. Only Leonard Jeffries has been excised as a character, perhaps because the television series Roots (the focus of his scene) has faded from the American memory; or perhaps this is due to the untenable claim made by the former CUNY professor that Jewish merchants played an instrumental role in the transatlantic slave trade, while Jewish filmmakers (including the ones behind Roots) played a key role in covering that up.

(© Joan Marcus)

Smith campaigned for a male actor to revive this play, and she's found an extraordinary one in Washington. He fully inhabits each character, marinating in their complexity and contradictions. His portrayal feels soberer than Smith's: As a woman playing dick-swinging men like Al Sharpton and Rabbi Shea Hecht, her performance had the spark of transgression that is inherent in great drag; laughter came much easier. Washington, who could legitimately play several of these characters in a made-for-TV movie, doesn't have that benefit (he is also a less operatic actor than the occasionally over-the-top Smith).

But Washington's natural performance style is genuinely felt, and easily believable. Director Saheem Ali stages an elegant production that keeps the focus on the actor: Arnulfo Maldonado's minimal set creates 25 different spaces on a bare stage, with just a desk, two lecterns, and a few coverings and props. This is still a show that could transfer to any university lecture hall. Dede M. Ayite's costumes use essential garments (a head covering for Lubavitcher women, a bow tie for a representative of Louis Farrakhan) to suggest distinct characters without requiring a lengthy costume change. Alan C. Edwards creates space with lighting, while projection designer Hannah Wasileski and sound designer Mikaal Sulaiman dredge up the sights and sounds of that terrible August in New York.

(© Joan Marcus)

Twenty-seven years on, Fires in the Mirror is still depressingly relevant because the same racial tensions stubbornly persist. If anything, they are more inflamed than ever, because segregation (whether state-mandated or self-selected) encourages members of one community to form an opinion of members of another based on very limited contact. "They runnin' the whole show," Gavin Cato's father says in the play's final moments about the Jewish people, "from the judge right down." And considering Cato probably rarely interacted with his Jewish neighbors until one of them ran over his son, it is unsurprising that he has landed on this anti-Semitic trope. How do we overcome such tribalism in a democracy, when so many people are happy to be left alone with their tribe? Smith doesn't offer any solutions, but she does force her audience to take a good, hard look in the mirror.