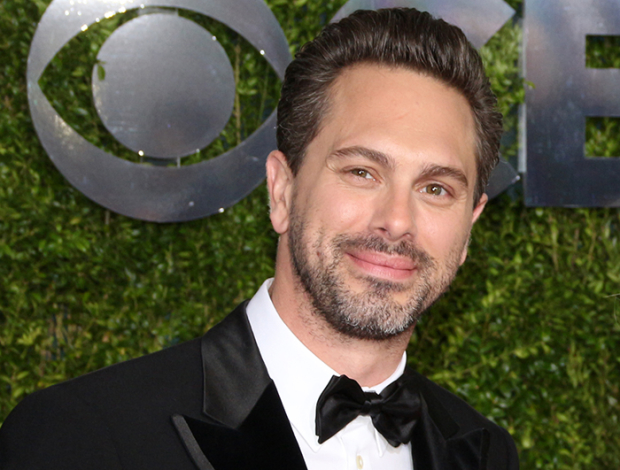

In White Noise, Thomas Sadoski Lays Down His Ego to Raise a Tough Conversation

For Sadoski, it’s worth the discomfort of delving into Suzan-Lori Parks’s dark play to participate in one of “the most important pieces of American theater in the last half century.”

In Suzan-Lori Parks's new play White Noise — directed by Oskar Eustis at the Public Theater — Thomas Sadoski, Daveed Diggs, Zoë Winters, and Sheria Irving play a quartet of college friends whose first deep dive into the conversation of race becomes a self-destructive runaway train.

Sadoski (a Tony-nominated actor and season regular on the CBS series Life in Pieces) plays Ralph — a frustrated professor and surprise trust fund baby who inherited his absent father's money after growing up in poverty. He comes to the aid of his insomniac best friend Leo (Diggs), whose sense of security is threatened by a violent cop during one of his late-night strolls. But rather than offering a salve, Ralph takes part in breaking open a centuries-old wound that — as many Americans may just now be realizing — was never properly tended.

(© David Gordon)

I think it's fair to say that White Noise takes some shocking turns. How did you react the first time you read it?

I sat down and read it and after I finished the first act, I called my wife and said, "I think I'm reading something really truly special." Then after I finished the play, I called her back and said, "I think I just read one of the most important pieces of American theater in the last half century."

I don't want to give too much away, but your character, Ralph, goes through a pretty disturbing transformation. How do you go to that dark place every night?

You can't have any ego when it comes to this stuff. I'm not out there to make people like me. It's my job to play this character as Suzan-Lori needs this character to be played, and I'm proud to take that on. It's not pleasant. I'm not gonna say that I'm having the time of my life. And by the end of the show, there's definitely a detoxifying period that has to happen. But in order for us to have the discussion that this play sparks, that role has to be done that way. So you just do it — and then a lot of breathing and a lot of leaving things at the door when you walk out of the theater.

Did you have any strong initial impressions about who Ralph was? And did that change over time?

I felt like if I came in with too many hard and fast ideas about who this person was, or why they were doing what they were doing, I limited my ability to be present for the conversation. On that stage every night, we are having the beginning part of a national conversation that we have been utterly incapable of having over the course of our history. So I came into this rehearsal process saying, "I just want to be here." There had been a period of time in which the group of us thought maybe we should soften the edge on this character and make him a little more "likable." As we sat with the play, we realized if we go around softening things too much, then all we've done is artistically replay the problem. Everyone has moments in the show of profound unpleasantness, and we can't soften those, because then we give the audience a place to hide. We also can't make things too cut and dry, because there's a lot of stuff going on in Ralph's life, driving him to these places that people can relate to. We're confronting all of it and we have to do that with the broken edges, because that's how we start this conversation.

(© Joan Marcus)

What exactly is the conversation? Does it come down to acknowledging the hard truths and continued legacy of slavery?

I think the conversation happens on a lot of fronts. But the first part is, everybody has to sit and acknowledge that these are facts. And from there we can move on. Because if you're not willing to identify universal truths, then there's no point in continuing. What a person needs in order to confront trauma I heard described best as having "a strong back and a soft front." What Suzan-Lori is asking of us is to sit with a strong back and a soft front.

It's certainly uncomfortable. Your character in particular is making the audience take a look at some pretty unflattering parts of themselves.

But that's what growth requires. You can't fix the problem with the same mind that broke it. You have to undergo a change in order to grow. And it isn't pleasant. I see that play out every night in that audience. There are a lot of people who are having very unpleasant realizations.

The inciting event in White Noise is one I could easily imagine audiences trying to neutralize by saying, "That could never happen." What would be your response to that?

My gut response to that is, why are you purposefully impeding the ability of art to reach you by requiring it to be as boring as real life? If you have a prerequisite that everything be documentary in order to learn anything about yourself, you pretty much just eliminated the entire purpose of art as it exists culturally — and why are you even in a theater? If it all has to be real-world experience, well then by all means, don't ever go to a museum, don't pick up a book, don't go to the movies, don't go to the theater, and never by any stretch of the imagination set foot in a f*cking dance studio. The whole purpose of art is to take things outside of the "real-world experience" and put them in a way that touches your heart, awakens your spirit, and connects with your mind so we're actually having a conversation as our full selves rather than just as people who are having our minds prodded.

There's also the other side of the argument, which is that truth is always stranger than fiction. So as much as you think that this might be completely crazy, there's a very good chance that there's weirder sh*t happening in the real world as we speak.

(© Joan Marcus)