Interview: Robert O'Hara Reinvents A Raisin in the Sun at the Public Theater

The Tony nominated director stages Lorraine Hansberry’s classic with a cast led by Tonya Pinkins and Francois Battiste.

In some ways, writer/director Robert O'Hara has long been under the spell of Lorraine Hansberry's A Raisin in the Sun. He first directed a production of this American classic in 2012 at the Geva Theatre Center in Rochester; two years prior, he imagined what members of Hansberry's Younger family looked like after five ensuing decades in The Etiquette of Vigilance for Chicago's Steppenwolf.

The summer prior to the pandemic, O'Hara returned to the text for a production at Williamstown Theatre Festival. Now, he's brought that revival to the Public Theater, for the first off-Broadway mounting of the seminal text in 40 years. But if you know O'Hara — writer of Bootycandy and Barbecue, and director of Jeremy O. Harris's Slave Play — you know that this is not going to be a conventional A Raisin in the Sun. Here, he tells us about envisioning the drama as a tragedy, with a focus on the female characters, instead of the man who walks in and out of their scenes.

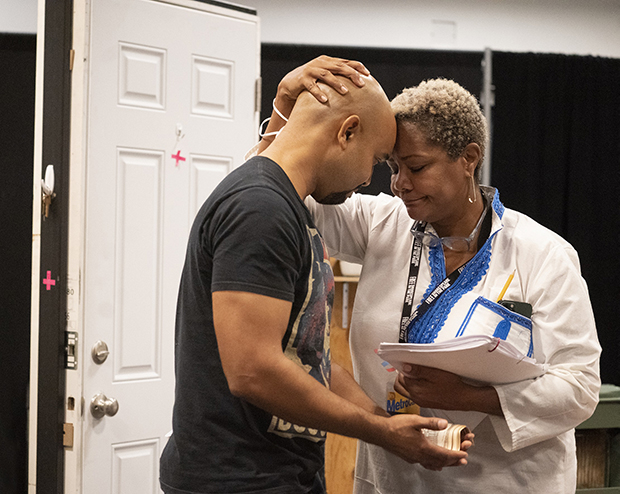

(© Zack DeZon)

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

This production started a few summers ago at Williamstown Theatre Festival. Did they come to you or did you go to them?

I had done a production at the Geva about 10 years ago, so I was not about to do another Raisin in the Sun. I had been speaking with Mandy Greenfield from Williamstown about doing something there, and she had been developing the idea of doing Raisin, which I didn't know anything about, and she called me and said she'd love me to consider it. When she said that, there were people already attached, who were people that I really enjoyed, and I had never directed at Williamstown before. I made very clear to her that I had a different take on the play, in that I look at it as a tragedy. I don't think of it as the story of a man trying to buy a liquor store. And that was something she embraced.

Those summer theater productions are done so quickly. How, in your estimation, did it go? Did you hit everything you wanted to hit, or did you feel like there was a deeper way to go?

Well, with a classic, there's always more to explore, and I was very excited by what happened at Williamstown. The only problem was that we never really got to shape it after performances began, because there's really no preview period. You can't go back in and continue working on something at summer theater. You get it up by the grace of God and close your eyes and squint. But the actors held it together and it was very exciting and was very well received. We were looking to somehow bring the production in, and then, of course, Covid hit. So that's where we were.

(© Joan Marcus)

I felt that your production in the Berkshires reinvented the play. I've seen the two past New York revivals, which were lovely and extremely respectful, but that doesn't leave you with the feeling that it could have been written yesterday, which yours did.

I think that's what we do with classics, especially classics that mean a lot to people, and Raisin, certainly, means a lot to a lot of people, so you better put it in a glass box with a sign that says, "Don't come too close." I will be messy and see if I can rearrange the furniture a bit, because that's what an exploration is. I can't have reverence for Raisin in the Sun and also interrogate it. There's also a little bit of fear of "What are you going to do with it?", you know? Because I have a reputation of doing new work and people don't see classics as new work. But I think that because Lorraine Hansberry was such a young writer exploring these different issues that she would appreciate an interrogation of her script. Off-Broadway almost allows you to bend the lens a little, whereas on Broadway, you need to make sure that you do no harm to the project with the product.

Do you see a connection between what Lorraine Hansberry talks about and where we are now?

All you have to do is say these things: housing crisis, racial polarization, abortion, alcoholism, poverty. And that's in the first 10 minutes alone. We are still constantly in conversation with these things. It's a no-brainer. I sit and I watch this play and I go "I can't believe we're discussing abortion in the first 15 minutes." She sort of frontloaded these things, which pays off brilliantly throughout.

So what does an off-Broadway Raisin in the Sun look like?

When the audience comes to see this at the Public, I want them to immediately say "This family has to get out of here. This is not inhabitable. This is not a place to be raising children." They have to feel the desperation. I've seen so many productions with two bedrooms, wallpaper, and I'm like "Can I move in? Why are you all leaving?" That's always been funny to me. There's real research that shows how people lived at the time and sometimes we like to clean it up, and I decided not to. I go directly into the reality of the poverty in the late 1950s in Chicago.

I think that there's not a responsibility to get it right or to make sure we don't break it, but there is a responsibility to make it speak to now. This play is not about, for me, Walter Lee. Walter Lee comes into every scene, and it's the women who started those scenes. Walter just walks in and out of those rooms. You have these three dynamic Black women in this show, and people want to make it about a man and his dreams. But what about their dreams? There are all those conversations that one can have around it that makes this production special.