Me, the World, and The Killer

Translate Ionesco, and who knows what planet you might wake up on.

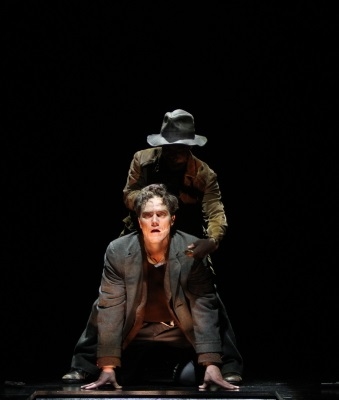

(© Gerry Goodstein)

I hadn't planned to mention, in this column, my translation of Eugène Ionesco's The Killer, which is currently in performance at Theatre for a New Audience's gorgeous new Brooklyn home, the Polonsky Shakespeare Center. And I hadn't planned to say anything negative about Ayad Akhtar's new play, The Who & the What, at Lincoln Center Theater's LCT3, which I very much enjoyed. But you know what they say about the best laid plans of mice and men. And if the mice are having as much trouble with their plans as we currently have with ours, I grieve for them almost as deeply as I grieve for our unworthy species.

Because this piece is all grieving, really. It's about violence. Ionesco's play looks straight at the world's violence, trying to map its many forms and find the reasons for them. Akhtar's play, which has gentler purposes, keeps its violence minor and discreetly offstage. I don't blame him. I'd like to keep it offstage myself. I wish it would go away. I wish the front page of The New York Times every morning were as cheerfully anodyne as Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. But it's not.

Ionesco (1909-1994) wrote The Killer in 1957. It had its New York premiere in 1960. Life was, or seemed, more placid back then. The traumatic global violence of World War II had started to recede from the forefront of human memory here in the West, supplanted by the comforts of the postwar economic boom. Violence then was a more sporadic phenomenon, seemingly located either in remote Asian countries or, here at home, mainly among troubled teens in bad neighborhoods.

In those days, Ionesco's play was perceived as an avant-garde foray into existential metaphysics, an examination of how one individual confronts the inevitability of his death. Which it is, in part. But Ionesco's plays rarely hew to a single narrative thread, and even more rarely lead to a simple, pat conclusion. The Killer is the first of four plays he wrote that centers on a man named Berenger. Commentators often describe Berenger as an "everyman," but he's hardly ordinary. Often, testing out alternative hypotheses as his opinions lurch from one extreme to the other, he seems more like a spokesman for the author. Yet few authors have ever made their spokesmen so epically impulsive and indecisive.

Berenger's confrontation with death — the play's dramatic core — itself seems to arrive purely on impulse: One day, having ridden the wrong bus to the end of the line (shades of Blanche DuBois!), he discovers a "radiant city," a 20th-century techno-paradise, and instantly decides to live there with his "fiancée" — a girl he's just met that minute. But like most paradises, this one contains a serpent: a serial killer who's been picking off the radiant city's residents, three a day. When Berenger's "fiancée" joins the list of victims, his goal switches from finding the earthly paradise to catching the killer.

That's when this play half a century old, already dotted with eerie prefigurations of our time, starts echoing today's headlines. The violence that was sporadic and distant in the late '50s has become a daily matter with us. Berenger's hyperactive mind, racing through all of the killer's possible motives, keeps zapping out unnervingly current lines. I wasn't the only one at rehearsals who felt genuinely perturbed when the shootings at UC Santa Barbara occurred, and the rant on the killer's website sounded like lines that Michael Shannon would speak every time we ran through Act 3.

School shootings have become frighteningly commonplace for us: There have been 74 incidents with guns at schools since Newtown, Connecticut. And they're not the only kind of violence that seems to surround us. Children stabbing other children have recurred as a motif in recent news stories. In one, outside Milwaukee, the teen-girl perpetrators thought they were following orders from a virtual person on a scary-story website. "Literature can lead to anything," Berenger tells Edward, in another of those lines that echo for me. When Edward protests, "We can't prevent writers from writing," Berenger replies, "Well, we should!"

That exclamation, Ionesco's joking rebuke to his own work, rang again in my head while I watched The Who & the What. Akhtar's play is in essence a charming, sweet-natured comedy about an immigrant family, in which a self-made, traditionalist father goes head to head with his intelligent, rebellious daughter. Jewish, Irish, Italian, and Chinese families have fought this battle onstage. Akhtar's aesthetic commitments seem to include bringing Pakistani-American Muslims to join them in the theatrical mainstream.

Therein lies his charm, his innovativeness — and my grief. Because today's Muslim world is fraught with dangers from which those other immigrant groups were on the whole safely removed. Akhtar's play flares into conflict when his heroine writes a feminist novel about the complex love life of the Prophet.

In Islamic terms, that's potentially gigantic trouble: We have the hunted lives of authors like Salman Rushdie and Taslima Nasrin for evidence. America has been spared, so far, the worst effects of such publication: Akhtar's not being untruthful when he limits the (offstage) reaction to his heroine's book to a few broken windows and resignations at her father's business. He clearly loves his characters too much to see them permanently endangered; his affectionate depiction makes us love them too.

But we still know that the outside world has played Akhtar false. He craves a happy ending for his people because he desires a world where our differences are settled amicably, with understanding instead of gunshots. Who could disagree with him about that? But the Islamic world outside is burning and exploding, and the stupidity of Bush and Cheney has dragged us into it up to our necks, Muslim Americans not excluded. The killer is loose worldwide. Like Berenger, we need to stop him, but nobody seems to know how. More about this, and other aspects of The Killer, next week.

(© Erin Baiano)

Stay tuned to TheaterMania for part II of this "Thinking About Theater" column, which will appear on Friday, June 27.