Miss Saigon

The popular musical about doomed love in the last days of South Vietnam returns to Broadway.

(© Matthew Murphy)

The 1990s are back on Broadway. Claude-Michel Schönberg, Alain Boublil, and Richard Maltby Jr.'s Miss Saigon has returned (via London's Prince Edward Theatre) to the very venue it played all through the last decade of the 20th century, but perhaps not quite as you remember it. Has the production changed in the last quarter-century, or have you?

Miss Saigon joins Cats and Sunset Boulevard revivals of popular shows from what seemed like a bygone era of self-serious excess. No one can predict if this resurgence of the British megamusical will last as long as the first time, but this contemporary take on Madama Butterfly from the guys who brought us Les Misérables makes a good argument for why it should be here.

(© Matthew Murphy)

The story begins in 1975, just before the fall of Saigon to Communist forces. American marines John (Nicholas Christopher) and Chris (Alistair Brammer) visit Dreamland, a sleazy nightclub run by the Engineer (an occasionally funny, but consistently grotesque Jon Jon Briones). John pays for Chris to spend a night with Kim (Eva Noblezada), a young orphan recently brought to Saigon. Chris is attracted to her modesty, but completely smitten when she refuses to take his money.

They decide to get married, a decision that proves hasty when soon after their wedding Chris evacuates without her. Her original betrothed, Thuy (Devin Ilaw), wants her to forget her faithless American husband. Still, Kim holds out hope that Chris will return for her and their son, Tam (Gregory Ye), completely unaware of Chris' new wife, Ellen (Katie Rose Clarke, doing her best in a thankless role). The political becomes deeply personal as these people try to live through the consequences of a war none of them started.

The original 1991 production of Miss Saigon arrived on Broadway in a storm of controversy over casting, subject matter, and ticket pricing — none of which has carried over to this revival. Producer Cameron Mackintosh and director Laurence Connor seem keenly aware of how audience sensibilities have shifted over the last 26 years and have crafted their revival accordingly. No actors appear in yellowface (a major source of contention in the original), but the portrayal of American malfeasance in Vietnam seems even harsher: Gun-toting soldiers snort cocaine and brutalize Vietnamese women in the opening scenes. It's shocking, but not likely to offend Broadway audiences, few of whom will bother to defend an unpopular war as it fades further into the rearview mirror.

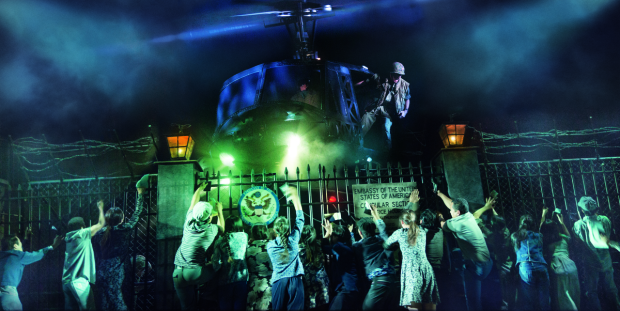

Fans of Miss Saigon will be pleased to see that the show retains everything that made it noteworthy in the first place: Schönberg's swelling ear-worm melodies, a massive ensemble of attractive dancers, and a realistic helicopter landing onstage in the second act. Let's be honest: That's really what you want to see anyway.

(© Matthew Murphy)

Production designers Totie Driver and Matt Kinley have created that effect in grand fashion: Well-concealed fans make us feel the whoosh of the chopper blades as the last evacuees from the American embassy fly toward the safety of the mezzanine. Bruno Poet's manic lighting and Mick Potter's immersive soundscape add to this dizzying experience. It's the closest you'll get to an amusement park ride in a Broadway house.

The talented ensemble fills out that heart-pounding scene and many others with unwavering commitment. Connor has opted for the more-is-more approach, packing the stage with bodies and scenery. Choreographer Bob Avian gives us back-flipping communist acrobats during the "The Morning of the Dragon," while the Bangkok-set "What a Waste" becomes an excuse to squeeze in as many references to other Broadway properties as possible including Priscilla, Queen of the Desert and The Book of Mormon. Costume designer Andreane Neofitou impressively clothes this army of a cast with detailed flair.

While Connor is traditional in his staging and design, his approach to the central love story is more unorthodox, and consequently more noteworthy. Brammer's charmless performance as the male lead is our first sign that something is up. He has a whiny tenor, the kind that would sound great singing Blink 182 covers in a pop-punk nostalgia revue. This Chris is a child, with little perspective on the world. "Why God? … Why me?" he squeals in his first ballad, asking for pity when his character is the least deserving.

(© Matthew Murphy)

The most deserving would be Kim, whom Noblezada embodies in a beguiling performance that asks for nothing. Her stony visage undermines the deliriously hopeful ballads she delivers, always with the precision of an Olympic figure skater landing a quadruple axel. She regularly breaks eye contact with Brammer during their love duets, peering over his shoulder like she's scanning the room to assess her options. They have zero chemistry, a choice that feel far more truthful than the typical Romeo and Juliet approach.

Noblezada plays a woman who has given up on the notion of true love before her first song. Romance is a luxury she cannot afford, but she does see the potential for a little material comfort from a credulous American admirer. Why shouldn't she have it? It's the least she deserves after her family is murdered and she is pushed into sex work, serving the foreign soldiers occupying her country. The fact that Noblezada looks all of 13 just compounds the tragedy of her situation. By the second act, she has given up on comfort for herself, transferring her aspirations completely to her son.

(© Matthew Murphy)

It's the kind of desperation that few people sitting in a Broadway house will ever personally experience, which is why it is all the more vital that it be presented there, in such a spectacular, tourist-trapping form. When you look beyond the hulking scenery and American Idol-style glory notes, you can see Miss Saigon for what it really is: a bruising indictment of American self-pity in an age in which we still control the lion's share of wealth and power.