Monica Piper Builds a Not That Jewish Comedy With a Lot of "Jewish Heart"

Over wry jokes and rye bread, the Emmy-winning ”Rugrats” writer explains a family tradition of funny.

(© Seth Walters)

"You make me so happy," says Monica Piper to the plates of coleslaw and kosher pickles the Ben's Deli waiter lays down on the table. "There's no New York pizza in L.A., but there's some really good delis in L.A."

Yes, she's a native of Riverdale, New York, and was raised a loyal Rangers fan, but Piper has grown fond of the backyards, hockey teams, and Jewish delis of the West Coast where she built a career as a television writer on shows like Roseanne, Mad About You, and (to Emmy-winning acclaim) the animated series Rugrats while raising her now 24-year-old son, Jake.

"You'd like him, he's really cute," she says, while digging through her phone for photos. Before the matzo ball soup and chopped liver sandwich arrive, Piper has shifted from interviewee to matchmaker. "We're arranging!" she yells to her publicist. "I'm showing her pictures of my son. It's her future ex-husband ."

It all sounds very Jewish, but Piper is the first to say she's Not That Jewish — nor is her solo show at New World Stages, which bears the same fitting title. "A lot of people come to the show initially thinking, 'Oh, it's a Jewish show. It'll be funny,'" she says. While Piper credits her sense of humor to her cultural upbringing — a brand of Judaism that she says included many more trips to the theater and Chinese restaurants than to synagogue — her family’s focus was less on the religious aspects of Judaism and more on "Tikkun Olam," a Jewish tradition of good deeds.

It's not misguided to expect Piper, a stand-up comedian by trade (a change-of-life path that followed a teaching career), to deliver her fair share of jokes. However, don't come expecting a 90-minute stand-up routine about the hilarity of temple on the High Holy Days.

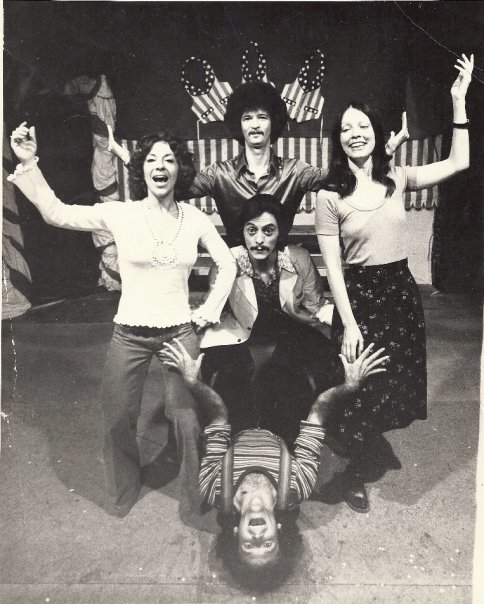

(Photo via Monica Piper's Facebook page)

"I wanted it to have some stand-up in it, but woven in and out of a story," says Piper. Even more than her work in comedy and television, storytelling became a prominent part of Piper's creative life is Los Angeles. "There are a lot of stand-ups who love storytelling because you don't have to get that laugh every two seconds. You can be really funny but with heart. That's why Rugrats was so great, because every story had heart. That was the formula for me."

Not That Jewish — which is inspired by a collection of family stories she wrote and performed at the Jewish Women's Theatre in Los Angeles — delves into Piper's divorce, her parents' deaths, the process of adopting her son, and a bout with breast cancer, which inopportunely cropped up when her son was at the peak of his rebellious teen years. "How many people do you know where cancer is not the worst thing in the house?" she quipped, followed by a raspy laugh.

(© Seth Walters)

There's nothing uniquely Jewish about any of those subjects, but Piper infuses them with "Jewish heart" — a phrase coined by her grandmother to indicate a combination of "good deeds, compassion, acceptance, and humor." In her show, Piper recalls a trip with her grandmother to the deli where they witnessed a man yelling a slur at a gay couple ahead of them in line. "My grandma started screaming at him at the top of her lungs. She's four feet eight inches, and she said, 'You with that fakakta hat on ya head! You're judging people?!' That's the kind of thing that made her irate. Inequality. So I grew up with those values," she explains.

Humor continued down the generational line to her father — born David Poss — who toured the country under the moniker Roy Davis with a lip-synching comedy act (eventually becoming a duo act with his wife, Fritzie). "My father and I would always find stupid things to laugh about," remembers Piper. "That's what we did all my life. It's the Jewish ability to find the funny in the darkest of situations as a means of survival."

(© photo courtesy of Monica Piper)

Next to pick up the comic tradition was Maylee Davis — the name Piper was born with and subsequently changed (just as her father did) for her comedy career. She toured the country doing stand-up and improv alongside legends like Jerry Seinfeld, Dana Carvey, and Robin Williams before opting for a stable life in Los Angeles with her infant son — the next link in her family's Jewish chain.

"To me, the thing was passing it down," she says — "it" being the Jewish identity that had passed from her grandparents to her parents and then to her. Yet, coming from non-Jewish birth parents, her son met the label with resistance. While at the time she considered this a "crisis," the challenge allowed her to reflect on her relationship with both her son and her audiences. "I didn't want any non-Jews in the audience to say, 'Screw that! You don't have to be Jewish to be a good person.'"

So in deference to her grandmother, she amended her stance: "He has a Jewish heart according to my grandma's definition, and that's good enough for me. What do I care if he doesn't go to temple or he doesn't call himself Jewish?"

"As long as he's passing down the funny stuff."

(© Carol Rosegg)