NYMF 2016: Forest Boy; The Last Word; Nickel Mines

This is TheaterMania’s fourth review roundup of the 2016 New York Musical Festival.

(© Clayton Jackson)

By Pete Hempstead

Scrabble fans attending NYMF this year should have one show in their rack: The Last Word, Brett Sullivan's lively, quirky new musical playing the Duke on 42nd Street. Michael Bello directs a stellar cast in this story about a man who, in order to save his Indian restaurant, makes a madcap cross-country trip with some friends to win the prize money in a Scrabble competition. The plot is as dubious as a phoney, but the performances are triple-word-score worthy.

Down-on-his-luck Jay Subasinghe (charmingly played by Nathan Lucrezio) has 10 days to come up with $12,000 before "parking lot mogul" Earlene (a delightfully evil Felicia Finley) tears down the restaurant left to him by his father (Herman Sebek in one of several energetically performed roles). With a flock of friends, Jay makes it to the National Scrabble Competition where two of them go head to head in a battle for bingos, but will it all spell disaster when love and Scrabble passions collide?

The Last Word, fortunately, doesn't take itself too seriously. With nutty numbers like "S-C-R-A-BBLE" and "Is That a Word?," the cast gets to show off Nick Kenkel's animated choreography. Sebek, whose dancing and singing chops are on display in almost every scene, is a thrill to watch. So is M.J. Rodriguez (recently in Encore! Off-Center's Runaways) as Jay's trans friend Carlise, whose well-timed sass and thrilling set of pipes add a welcome energy to songs like "The Word Is Out!" and "Find My Way Home!" As Jay's other Scrabble friend Benny, Philip Jackson Smith is a riot, and he delivers some of the show's best one-liners.

But, like Sullivan's characters, the plot gets sidetracked along the way. The friends try to fleece senior citizens at an old-folks home in the song "Dementia," which barely skirts being offensive. And by the end Jay is no longer the main character. Instead, a love affair between friend Neil (Travis Kent) and Jay's sister, Santine (Jessica Jain), leaves him and his plight in the shadows. The wayward story and some corny lyrics ("You're the bingo I've found," "A Q's no good without U") can make The Last Word as frustrating as a rack of vowels, but the performers and the band, led by Conrad Helfrich, keep the show up-tempo and F-U-N.

(© Paul R. Kennedy)

By Zachary Stewart

On October 2, 2006, Charles Roberts walked into an Amish schoolhouse in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, and murdered five girls, injuring another five. This real event is the basis for Nickel Mines (the name of the school), a moving and highly unorthodox new musical.

In a program note, the authors describe the piece as a "living memorial" to the victims. Appropriately, all 10 are depicted onstage, wearing spectral white dresses (simple and evocative costume design by Sera Bourgeau) and performing director Andrew Palermo's violent choreography. Their expressions of horror arrive in unison, to chilling effect. A heart-pounding scene depicting multiple calls to 911 helps us to physically feel the confusion and panic of that day.

By contrast, Dan Dyer's melodic and folk-infused score reaches our ears like a gentle whisper. The recurring "Psalm of Samuel," sung by the extraordinarily talented Morgan Hollingsworth (playing Samuel, a wayward survivor who went on Rumspringa after the shooting and never returned), is one of the most joyous and touching love songs I have heard in a long time.

In writing their highly experimental book for Nickel Mines, Palermo and Shannon Stoeke have eschewed traditional character development and linear narrative in pursuit of a deeper truth and emotional resonance. They half succeed, conjuring a dream-like state onstage. In fact, it is so entrancing that it nearly lulls us into slumber, as one soft-lit scene of interpretive dance bleeds into the next. Still, there's a lot to like and be impressed with in this undeniably beautiful musical about a frustratingly relevant subject.

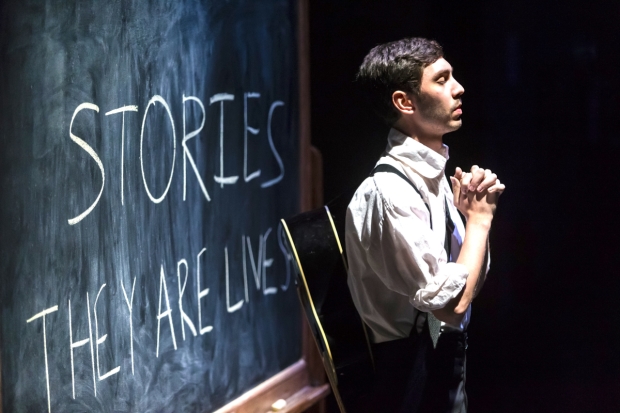

By David Gordon

On September 2, 2011, a twentysomething Dutch man named Robin van Helsum went missing. On September 5, 2011, "Ray" showed up at Berlin's Rotes Rathaus claiming that he had been living for five years with his now-deceased father in the forests of Germany. Dubbed "Forest Boy" by the media, he was believed to be a minor and was provided with government-sponsored shelter and education. But the police investigation into his story proved otherwise.

The tale of the "Forest Boy" is fertile dramatic territory, with everything an author could want: questions of identity, blatant falsehoods, and a figure with a secret at its center. But a compelling psychological drama, let alone one with songs, is a hard thing to create. The evidence is Forest Boy, a musical by Claire McKenzie and Scott Gilmour, which, despite the constant feeling of repetition, shows some promise.

There are two stories in Gilmour's script. The first takes place in the mind of Ray (Will Connolly, nicely pained throughout), where he envisions living in the woods with his dad (Christopher Russo, believably fatherly), and the conflicts that such isolation would bring. The second is in real-world Berlin, where a police detective (the authoritative Remi Sandri) attempts to uncover the story of Ray's existence in the trees. The different viewpoints don't work together, with the direct-address, docu-drama style of the latter making it difficult for the two to coalesce.

Forest Boy does have a few things going for it. There's a lovely earthiness to McKenzie's acoustic score, which she also orchestrates for a five-piece band led by Wiley DeWeese (though too many of the songs sound the same, and Gilmour's lyrics have a tendency to veer into the opaque). Movement director EJ Boyle provides frenetic choreography that resembles how we envision brain activity, while director Robert McQueen pulls fine performances from his cast.

Those familiar with the story of the "Forest Boy" won't be taken aback by the show's outcome, but that said, neither will perceptive audience members who are skilled at predicting the ending from the start. Perhaps this musical hews too close to reality and might be better off staying inside Robin's head in order to retain an element of surprise.