Party People

A new musical at the Public Theater examines the legacy of the Black Panthers and Young Lords Party.

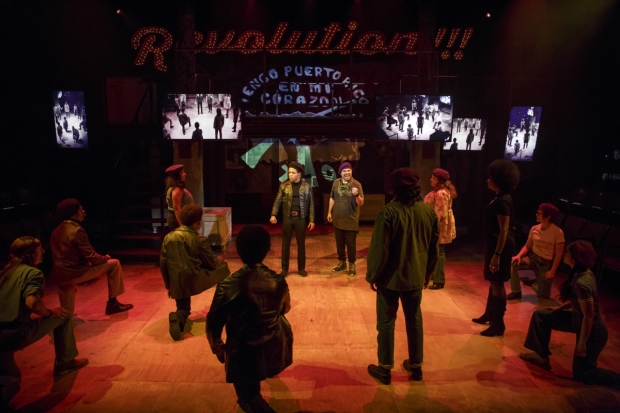

(© Joan Marcus)

It seems more important now than ever before to know our history: Which political movements were successful, which weren't, and why? Party People, a new musical commissioned by Oregon Shakespeare Festival and now making its New York debut at the Public Theater, attempts to answer those questions, specifically as they pertain to two of the most radical civil rights groups.

Party People features a script devised by the internationally produced theater ensemble Universes (Steven Sapp, Mildred Ruiz-Sapp, and William Ruiz a.k.a. Ninja, all of whom appear in the show). The group has collaborated with sound design collective Broken Chord on pulsating new songs for a theatrical experience that feels like a radical episode of American Bandstand, with nonstop music, movement, and energy undergirded by scant thematic substance. Audience members might want to think twice before they RSVP.

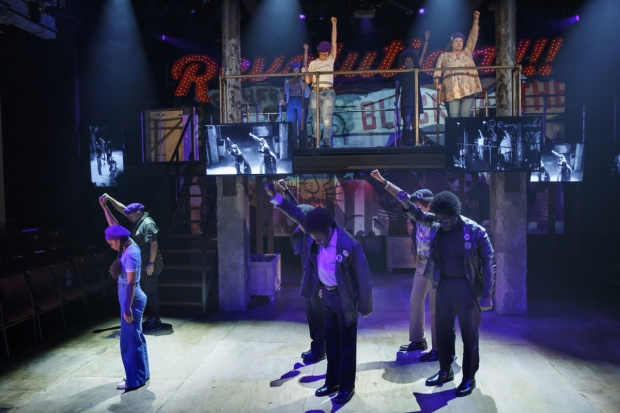

(© Joan Marcus)

The story takes place around a reunion party for the Black Panthers and the Young Lords Party, a Puerto Rican Nationalist group that once organized a series of trash burnings to protest erratic collection in Spanish Harlem (this event features prominently in the off-Broadway musical I Like It Like That). Millennial activists Malik (Christopher Livingston) and Jimmy (William Ruiz) are producing the event, which they plan to stream live on Facebook (embracing the vertical-video revolution, projection designer Sven Ortel strategically mounts flatscreens all over the room). Some of the participants are wary, like aging Panther Omar X (Steven Sapp) and Jimmy's uncle Tito (a convincingly grizzled Jesse J. Perez). They're worried about their legacy being tarnished and hesitant to open old wounds.

And they should be worried: Camera always at the ready, Malik treats this like a Real Housewives reunion special, complete with surprise guests and stage-managed confrontations. Between these, the ensemble performs educational musical numbers about FBI infiltration and the drug epidemic. Meanwhile, Jimmy uses the opportunity of a captive audience to showboat his performance-art alter ego, Primo the Clown.

(© Joan Marcus)

As Primo, Ruiz portrays the most insufferable theatrical creation in recent memory: Sporting a Kermit the Frog voice and armed with a long microphone, Primo is determined to school us in the most grating ways possible. At one point, he sticks his mic in the face one bewildered audience member and asks him for the first point on the Young Lords Party platform. He then launches into a self-congratulatory rap as the names of people recently murdered by the police scroll across the screens. It all feels incredibly exploitative with very little redeeming value. Perhaps this is a comment on the counterproductive narcissism of modern performance activism, but Primo is so obnoxious that we don't even care to ponder; we just want him to go away.

The normally rigorous director Liesl Tommy (Eclipsed) delivers a production that does little to clarify the haphazard script and regularly skimps on the basics of efficient direction: The stage often appears crowded and the blocking aimless. At this gathering of veterans from revolutionary black and Latino organizations, we wonder: Who are all the white people in headsets moving the furniture around?

This is unfortunate since this tireless 12-person cast seems more than game for any physical challenge thrown their way. Between singing, dancing, and reciting spoken word, they all break a sweat and gasp for air, especially after performing Millicent Johnnie's aerobic choreography, which would have looked perfect in a celebrity workout video starring Huey Newton.

Of course, there's no Lycra to be found onstage: Meg Neville outfits the actors in an array of denim and heavy military jackets. It all looks very authentic, but it's not something you'd want to dance in. The actors bound up and down the metal stairs of Marcus Doshi's set, which offers multiple levels but feels a bit too big for the Anspacher stage. Extending across the upstage wall is a very large and expensive-looking Las Vegas-style sign reading "Revolution!!!," a monument to useless extravagance.

(© Joan Marcus)

In the final 10 minutes, the older characters directly confront the younger folks about their hashtag activism. "Every generation since ours has been systematically taught how to be better oppressed, how to be quiet," Amira (an on-point Ramona Keller) bitterly observes. "You think wearing a hoodie and calling yourself Trayvon means something?" But perhaps these old Panthers and Lords don't have much room to judge, since we're still struggling with the same issues of police brutality and systemic racism that they confronted head-on in their heyday. Has anything changed? Finally, we understand the previous two hours and 15 minutes as an overture to the real, meaty generational drama at the heart of the play. For a brief moment, Party People is raw, honest, and thrilling. And then it ends.

This is a shame because our country urgently needs a discussion about how to use the lessons of the past to respond to the persistent injustices of today. Sadly, Party People isn't it.