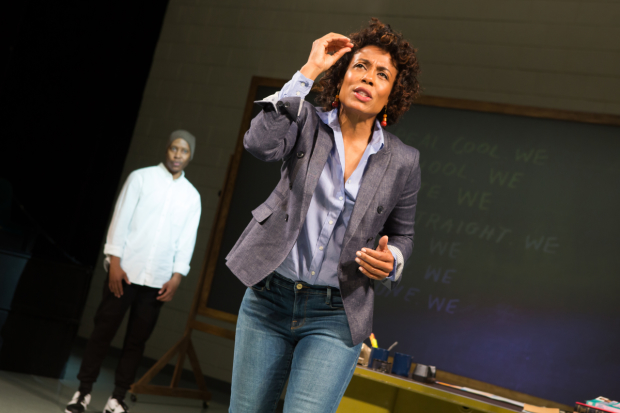

(© Jeremy Daniel)

Debate about the "school-to-prison-pipeline" typically pits the necessity of law enforcement against the dangers of mass incarceration. The result is a battle between nebulous concepts and faceless victims, all operating in a system too convoluted and baggage-ridden for anyone to wrap their minds around — particularly if they personally have no skin in the game, which, I would venture to guess, not many of Lincoln Center's regular audiences do. Simply watching Dominique Morisseau's Pipeline, of course, can't do anything to change that, but it can — and does — elevate the conversation beyond statistics to a flesh-and-blood level that shows us just how much we don't know that we don't know.

The most revelatory aspect of Morisseau's 90-minute drama is how it reframes this storied school-to-prison pipeline as a society-to-prison pipeline. When violence erupts in the classroom or drugs run rampant through the hallways, is the school the cause or just the most convenient breeding ground for a path already set in motion? Morisseau's central character, Nya (an excellent, anchoring performance by Karen Pittman) — as both a New York City public school teacher and the mother of what politicians would call an "at-risk youth" — would like to think that school, if not the cause, can at least be the cure. But perhaps it's neither and both at the same time.

Nya teaches English at a school that most would write off as one of the "pipelines" from which to escape. It's surveilled by metal detectors and policed by security officers, who frequently have to break up life-threatening brawls between students. And yet, it's staffed by some excellent educators — including Nya and her longtime coworker Laurie (a hilariously brash Tasha Lawrence) who enters the classroom everyday with the devotion and determination of General Patton. A young security staffer named Dun (played with a fullness of heart by Jaime Lincoln Smith) softens the threatening air of his uniform with a sunny disposition (and charms Nya, with whom he shares a vague and history-laden flirtation).

However, submitting to the will and financial jurisdiction of her mostly absent but well-off ex-husband Xavier (an imposing Morocco Omari), Nya has agreed to send her teenage son Omari (Namir Smallwood) to a fancy boarding school where, theoretically, opportunity is bred. Yet this beacon of white-collar hope can't even put an end to Nya's tireless struggle to keep Omari on the right path — particularly after he comes to blows with a teacher in the middle of a lesson on Richard Wright's Native Son.

So did both schools fail Omari? Did Omari fail both schools? Or, is there an invisible power surrounding it all that's proliferating this pattern of destruction? Morisseau argues the latter through Omari, in whom Smallwood shows the frustration of trying and failing to put into words what transpired in the classroom to bring him to his explosive state. His mother's counterarguments of personal responsibility are clearly the ones that would hold water in court, but Omari's words plant a seed that nearly tears Nya apart. Pittman gives powerful voice to the feelings of crushing futility that come with the realization that whatever she does — both as an educator and a parent — it's checkmate for her son.

Thorny debates within complex social structures are never lacking in Morisseau's work, which often deals with untangling the massive web of conflict embedded in American society. The only pitfall is that the characters in Pipeline take a backseat to the ideas they're there to present, giving the impression that we're hearing the voice of the playwright rather than her characters.

However, it's hard to wish any of her monologues away — each one its own work of poetry. Heather Velazquez, delivers several of them as Jasmine, Omari's girlfriend and fellow member of the boarding school's lower class. Jasmine serves as an unexpected font of wisdom about the "opportunity" a steep tuition can buy while also providing comic relief with her naïve teenage philosophizing about life and love. Smallwood delivers a gut punch in his final monologue — a confession to his estranged father about the part their relationship has played in his current situation.

With Gwendolyn Brooks's 1959 poem "We Real Cool" a constant and haunting backdrop inside the free-flowing space that holds Matt Saunders's set design, director Lileana Blain-Cruz and her creative team lean into the lyricism of Morisseau's writing, even as plot starts to sputter. Lighting designer Yi Zhao transitions from the fluorescently lit school break room to shadowy recitations of Brooks's words while projection designer Hannah Wasileski fills out scene transitions with images of violence in school hallways and buses. The result is a play that offers a snapshot of today with ghosts of the past standing at the other end of an invisible pipeline that will never be dismantled until we acknowledge how it got there.