Point-Counterpoint: Should Children Perform on Broadway?

TheaterMania’s critics debate the practice of casting child actors in the professional theater.

(© Matthew Murphy)

Never work with children or animals, goes the old showbiz adage. Yet plenty of Broadway producers regularly do both. Seven Broadway shows currently feature child actors, the kid-tastic School of Rock being the most notable example. Child actors have been particularly feted on Broadway in the past decade, with the three original Billy Elliots winning the Best Actor in a Musical Tony in 2009 and the four original Matildas earning a special Tony in 2013. But is it really appropriate to celebrate children performing adult jobs and earning adult wages? In TheaterMania's latest point-counterpoint, critics Hayley Levitt and Zachary Stewart debate the ethics and artistic value of having child actors on the professional stage.

(© Seth Walters)

Zachary Stewart: Hayley, I've enjoyed your many interviews with young actors. Has that reporting given you any insight on the practice of casting children in Broadway shows? Specifically, why does it happen so often, and is it a good thing?

Hayley Levitt: Everyone at work knows that one of my favorite things to do in this job is interview the kids of Broadway. They're so quirky and fun and living the musical-theater dreams of every little show queen in America. That being said, I've seen close up how each production is responsible for setting the right tone for the young actors it hires. When it's done right, I think professional theater can be a really supportive and healthy environment for a talented young person — like a creatively charged classroom that challenges its legitimately interested students. But when it's done wrong, you can definitely find some zonked-out robots who sound like they've been media-trained by Stepford Wives.

Broadway hires so many kids because it draws audiences — particularly family audiences, which is the gold mine for commercial theater. But just because capitalism is the engine behind the industry, doesn't mean we have to treat the kids inside of it like cogs. In most cases, I don't think we do.

Zach: I appreciate that producers go through pains to make their shows kid-friendly workplaces, but that still doesn't mitigate the fact that kids are working. Can you think of any other profession in which children make up a significant part of the labor pool? It not only makes me worry about what these kids are missing by spending several hours every week at work, but it makes me concerned with how theater is viewed in broader society. If it's the kind of "fun" job for which standard laws against child labor don't apply, what other labor laws can we ignore when it comes to actors?

(© Matthew Murphy)

Hayley: Child labor laws were instituted because underage children were being forced out of school and into the work force to help support their families — and the work they were impelled to do was hard labor that would actually harm their physical development. If we're looking for reasons why child actors are governed by their own, less prohibitive set of labor laws, those I think are legitimate distinctions.

Aside from the pay, what's the difference between a professional child actor and a kid who dedicates him- or herself to an instrument or sport? There are preteen gymnasts who spend over 30 hours a week training for the Olympics and they don't even get paid. Ultimately, each family has to determine the right balance for themselves.

Zach: The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 sets 14 as the minimum age of employment (and then only in a limited set of jobs). However, a series of provisions colloquially known as the "Shirley Temple Act" exempts actors (and, more distressingly, farm workers) from these rules; and while dancing on the Broadway stage may not be as labor-intensive as field work, it is clear that both require a certain amount of physical exertion. That lack of federal oversight also means that the regulation of child performers is left entirely to the states. Seventeen states have opted not to exercise this privilege, but New York is not one of them: Under this state's rigorous law concerning child entertainers, you can start your acting career at 16 days old.

Hayley: New York also stipulates that at 16 days you can only be on set for two hours a day and work for 20 minutes of those two hours. Yes, there are loopholes that can be exploited, but if we close them, productions that feature casts of kids can be life-changing. The West End revival of Oliver! was one of the first shows that got me obsessed with musical theater — and that was because it was a bunch of kids my age singing and dancing about a camaraderie that was separate from the world of adults. There's something affirming about seeing people like you represented onstage. Giving children the opportunity to have that experience makes it worth fixing the system, rather than throwing the whole thing out.

(© Joseph Marzullo/WENN)

Zach: Ideally, I would like to see a theater without child labor, but that is an unrealistic expectation. Still, it is disappointing to me that such an imagination-based art form is so reliant on the presence of actual children to represent children. Clever writers and directors can find a way to theatricalize children while also deepening the themes of their play, as we recently saw in Log Cabin (which featured an adult playing a very precocious infant). And while I'm sympathetic to the call for representation of all types of people onstage, I don't think it needs to be perfectly literal. Ultimately, by insisting on actual kids to play kids, we're encouraging unimaginative storytelling for unimaginative audiences.

Hayley: Having kids play kids isn't necessarily unimaginative. If I'm a young girl watching Matilda: The Musical and Matilda is played by an adult, I'll conceptually understand she's playing the role of a child, but I'll still have a harder time identifying with her. In the back of my mind I'll be thinking that all this power Matilda has — even though she claims to be my age — is still reserved for people who look like adults.

And speaking of Matilda (which did sneak some adults into the ensemble of Crunchem Hall students), that was a show that I think did a great job handling its young leads. The title role was shared equally by four girls, which cut down the workload, and press was always done together. The character was the focus, not the performer. I never met any diva Matildas.

Zach: I agree that Matilda is the gold standard when it comes to limiting the impact of Broadway on child performers, but even that show wasn't able to solve the uncomfortable problem of kids aging out of their roles, which isn't as much of an issue for adult actors. As former child star and movie Matilda Mara Wilson succinctly put it, "It's basically a real-life version of Logan's Run. A child actor who is no longer cute is no longer monetarily viable, and is discarded."

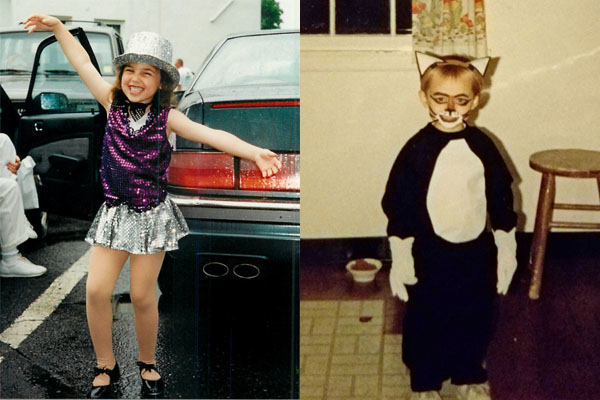

(Courtesy of Hayley Levitt and Zachary Stewart)

Hayley: The commercialization of looks is a sickness of the entire entertainment industry, not just the part that involves children. But, to your point, kids, unlike adults, aren't in a position to (and shouldn't have to) understand those kinds of repercussions. What we can do as the adults in the room is not exacerbate the problem, which we definitely do when we throw adult awards at them. Awards are a twisted mind game for adult performers — we shouldn't make kids try to figure them out, too. That's one productive line I think we could draw.

Zach: I second that motion. No more Tonys for tots.