Review: 7 Minutes Dramatizes the Breakdown of Trust Between Workers and Employers

The playwright behind ”The Lehman Trilogy” turns his attention to labor.

(© Julieta Cervantes)

"Nobody wants to work these days," goes a refrain popular with genuine members of the ruling class (like Kim Kardashian) on down to those who only imagine themselves as such (your uncle who manages a KFC). But is it really that no one wants to work, or that no one wants to work for you and under these conditions, constantly accepting less while giving thanks for even having a job? Stefano Massini powerfully captures the angst of working people in the age of deindustrialization in 7 Minutes, which is now making its English-language debut (in a crackling translation by Francesca Spedalieri) with Waterwell, in association with Working Theater, at HERE.

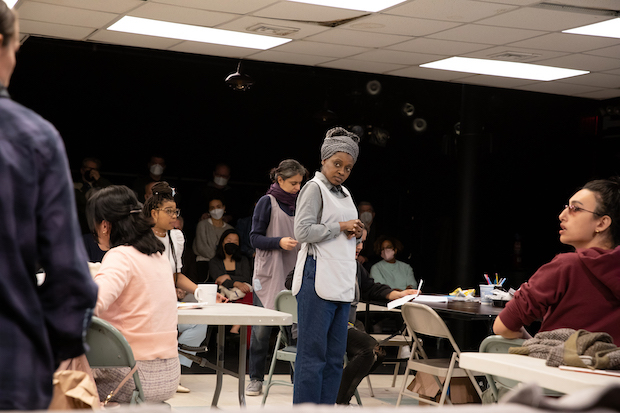

Massini is best known in New York for The Lehman Trilogy, which mythologized one American family's rise to the dizzying heights of capitalism. In 7 Minutes he gives us the perspective of labor, specifically the union executive committee of Penrose Mills, a Connecticut textile factory recently under new management. The 11 members of the committee have been tasked with representing all 200 workers in talks with the new owners, and only one, Linda (Ebony Marshall-Oliver), has been chosen to be in the room with the "suits" when they explain their plans. All expect bad news — layoffs, reduced hours, slashed benefits. And all are relieved to learn that management is asking for just one concession: that every employee give up seven minutes of break time. All intend to quickly vote to accept this proposal — all except Linda.

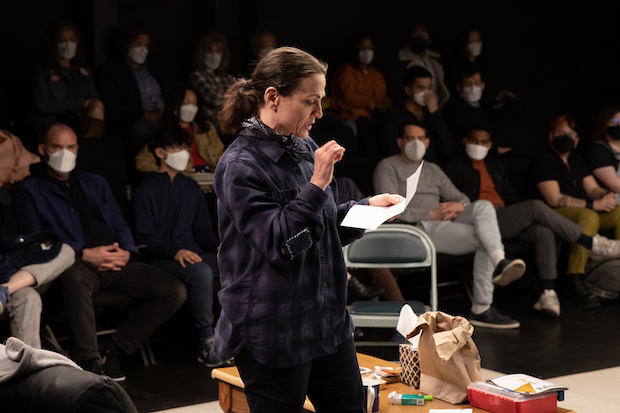

Following in the footsteps of Reginald Rose (Twelve Angry Men), Massini deftly dramatizes something increasingly rare in the age of ideological trench warfare: persuasion. Completely outnumbered, Linda sets out not to browbeat the other women into submission, but to calmly and clearly convey her doubts about this supposedly great deal.

(© Julieta Cervantes)

"If they'd asked for everything at once they wouldn't get it, there would be conflict," she reasons. Marshall-Oliver gives Linda a steady voice, deliberate without being overly confident. Such humility engenders trust and stands in stark contrast to the smarmy HR-approved pitch offered by management in the individually addressed letters offered to each member of the committee. "They have another way," she argues, "this one. Smiles. The letter. Only seven minutes. How can one not accept? And since everything is telling us to accept… I say we turn it down."

"This is nonsense," retorts Danielle, Linda's most vociferous opponent, played with scorching intensity by Danielle Davenport. "We should thank them." This is a matter of life-and-death for her, since her insurance covers the cost of a family member's dialysis (this represents a raising of the stakes from the original Italian version, which was set in France, a country with national health insurance). But Linda wonders how fair a negotiation can be when one party is clearly more desperate than the other — and if they capitulate on something small right now, what more will the new owners take from them, bit by bit?

(© Julieta Cervantes)

Mei Ann Teo's dynamic staging in the round makes us flies on the invisible walls of You-Shin Chen's authentically depressing break room set, complete with fluorescent lights in a drop ceiling. Lighting and sound designer Hao Bai amps up our nerves with a pre-show loop that simulates the noise of the factory floor. She also manages to heighten moments in the play with more low-tech cues, like the sound of a boiling tea kettle onstage. Asa Benally's costumes give us our first indication of the fissures in labor solidarity: While most of the women wear overalls or other work clothes, two of them (Carmen Zilles and Aigner Mizzelle) sport business casual. They work in the office and have a better sense of the numbers.

Blue vs. white collar isn't the only conflict that arises over the course of this 90-minute thriller: In Mahira Kakkar's agonizing doubt (as Denise) we see the disappointment of an older generation leaving less to their children. In Julia Gu's pugnacious determination (as Alex), we understand the exhaustion of a young worker who has already experienced that diminished quality of life and isn't willing to go back now that she has a decent job. And in Jojo Brown's simmering rage (as Jordan), we see a person who is trapped in a bad situation and is looking for someone to blame — perhaps immigrants like Leyla (Layla Khoshnoudi) and Mahtab (Nicole Ansari).

(© Julieta Cervantes)

The latter delivers the most exhilarating speech of the play, one-upping Marshall-Oliver in terms of calmly articulated devastation. Mahtab is originally from Iran, and her formative experience in a country whose liberal revolution ceded to theocracy has left her unable to trust. How can she know that rejecting these generous terms won't give the suits a pretext to offer worse ones? Her fear is well-founded: The population grows larger; the means of production become ever more efficient; and foreign labor is plentiful and consistently cheaper. These trends are unlikely to change barring a devastating pandemic or a world war — neither of which is completely out of the question.

Speaking of pandemics, I've attended performances at several theaters that purport to have a KN95 mask requirement, but HERE is the first venue I have encountered to really mean it, offering each patron a mask at the door. I wore mine throughout the performance, as requested, although there were enough empty seats that I was technically "socially distanced" from the next closest audience member. This is a shame, because 7 Minutes is one of the most electrifying dramas in New York right now. Don't miss your chance to see it.