Review: Alice Childress's Rarely Seen Classic Wedding Band Ignites the Stage

Awoye Timpo directs a brilliant cast in a new production for Theatre for a New Audience at the Polonsky Shakespeare Center.

(© Henry Grossman)

It's been 50 years since Alice Childress's Wedding Band appeared in New York, after premiering at the Public Theater under the direction of Childress and Joseph Papp in 1972. Ruby Dee led the cast then as Julia Augustine, a Black woman in a 10-year romantic relationship with a white man in 1918 South Carolina. The play received praise from critics, but never moved to Broadway.

Why that is, and why Wedding Band hasn't been revived in the city until now, we could speculate on for days. But we can also be grateful that it has finally been brought back, at Brooklyn's Polonsky Shakespeare Center, in a breathtakingly powerful production for Theatre for a New Audience. Awoye Timpo directs this modern classic with her usual laserlike focus, taking the play down to its raw nerves and eliciting razor-sharp performances from an extraordinary cast. By turns hilarious and gut-wrenching, this production of Wedding Band needs to be seen.

(© Henry Grossman)

Part of the reason for that is the play's uncanny resonance. It's set during the First World War as America endures a pandemic, and racial tensions simmer beneath everyday interactions. Brittany Bradford, in a virtuoso performance, plays Julia, a seamstress who has rented out a house from Fanny Johnson (a regal Elizabeth Van Dyke), the only Black woman in her town to own property. This is the latest in a string of residences that Julia (costumed in a period-specific dresses by Qween Jean) has taken up, since in South Carolina it's illegal for her to be in a sexual relationship, much less in a marriage, with her longtime love, Herman (an endearingly conflicted Thomas Sadoski), a white baker whose racist family and upbringing complicates their relationship and reveals itself in predicable and unexpected ways.

That sense of wandering and searching for a home is captured in Jason Ardizzone-West's set, a traverse stage that suggests the marshy, reed-growing land of a coastal South Carolina town. Julia's room is set amid this dismal vegetation, which lighting designer Stacey Derosier subtly illuminates to indicate changes in scenes. We long for her and Herman to escape this sepia-toned world for their chance at happiness.

(© Hollis King)

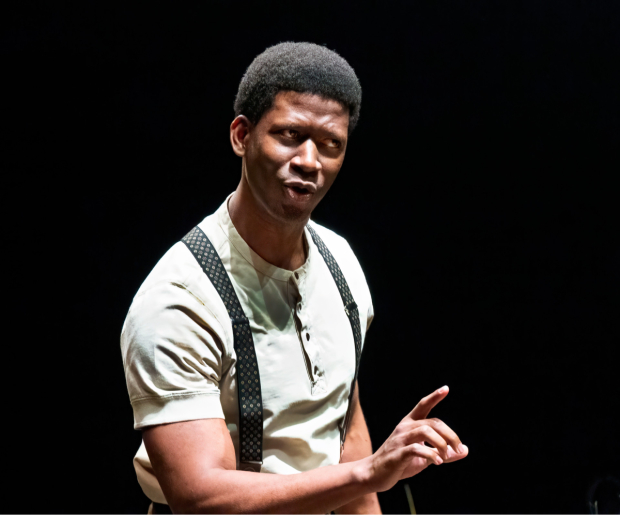

Others in the neighborhood's tight-knit coterie of women have found coping mechanisms for living amid unabashed bigotry. There's Mattie (a wonderful Brittany-Laurelle), a poor woman hoping against hope for the return of her merchant marine husband while she cares for their daughter, Teeta, and babysits a white child, Princess (Phoenix Noelle and Sofie Nesanelis, respectively, in adorable performances). And there's the placating Lula (a memorable Rosalyn Coleman), who will do anything to protect her adopted son, Nelson (Renrick Palmer playing a Black soldier who refuses to bow to whites), even if it means smiling at the petty tyrannies of a racist peddler (Max Woertendyke in a small but noteworthy role).

Timpo builds our interest in these characters in the first act with clear delineations of their personalities and motivations, and she creates tension as they react to Herman succumbing to the virus that is sweeping across the country (composer Alphonso Horne and music director Mehemiah Luckett heighten such moments with haunting incidental music).

(© Hollis King)

But Timpo saves the real emotional pyrotechnics for the second act, where Herman's family appears, and insists on pushing Julia aside to care for him on his sickbed. Rebecca Haden effectively plays Herman's dithering sister, Annabelle, and Veanne Cox, her jaw clenched as though it could grind marble, plays his mother, an old-school racist matriarch whose hard life has turned any compassion she may have had to stone. Her ferocious standoff with Julia, a vicious exchange of insults and recriminations, left me clenching my fists and holding on to my seat. The audience's proximity to the stage and Rena Anakwe's crisp sound design make that and other fiery encounters visceral and jarring.

Childress's fearless and unapologetic writing allows scenes like that work, even a baffling moment when Herman, in the delirium of his illness, rattles off an incendiary speech by US Vice President and defender of slavery John C. Calhoun. Whether this is Herman trying to placate his mother, or Childress depicting the kind of racist statements that sometimes burble from the mouths of even the most well-intentioned white folks, is up for interpretation.

Regardless of the strangeness of this scene, the power and importance of the play remain. Broadway audiences recently had the chance to discover another Childress play, Trouble in Mind, in an terrific staging starring LaChanze and Chuck Cooper. Wedding Band speaks even more directly to us now, and it would not surprise me if it makes its premiere on Broadway sometime soon as well. Until then, this exceptional production should be your introduction to a play whose author audiences can no longer afford to overlook.

(© Henry Grossman)