Review: Despite Admirable Intentions, Seattle Rep's Jaws-Inspired Bruce Barely Stays Afloat

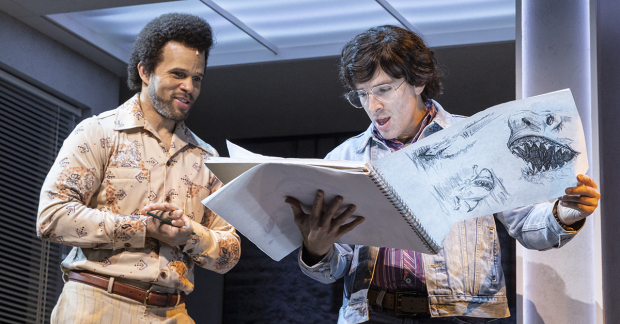

Jarrod Spector plays Steven Spielberg in a new musical from the creators of ”Bandstand”.

(© Lindsay Thomas)

In the summer of 1975, Jaws opened on the big screen to critical praise. Now considered to be the first summer blockbuster, the film jumpstarted the career of a young director named Steven Spielberg. In the years since, the behind-the-scenes story of the disastrous making of Jaws has been chronicled in numerous documentaries and books, including Carl Gottlieb's bestseller The Jaws Log. Now, almost 50 years later, the story has been turned into a musical. Though Bruce, now running at Seattle Rep, has respectable intentions, it is bogged down by too much exposition, a weak score, and too short a runtime.

Bruce, written by Bandstand collaborators Robert Taylor (book/lyrics) and Richard Oberacker (music/book/lyrics), and directed and choreographed by Donna Feore, follows the development of Jaws from novel form through the long and troubled six-month film shoot. Steven Spielberg (Jarrod Spector) is a young director with a childlike wonder and is ready to make the "Big One," as expressed in the opening number. Fresh off a smaller-budget film, Jaws is his chance to prove to Universal and the public that he has what it takes to be as good as his cinematic heroes.

Though the concept of Bruce (named for the ever-malfunctioning mechanical shark) has great potential, neither Taylor's book nor Oberacker's score ever soar. The songs are musically uninteresting, and the book hastily introduces us to a host of individuals who are just as quickly forgotten. The show is so focused on retelling historical events with accuracy that much-needed character moments are cut short. Consequently, we have little time to care about what is transpiring. Before we know it, these brief moments have passed and the background information we have learned is so irrelevant to the story that it is difficult to understand why the writers even went to the trouble.

Familiar figures are portrayed by actors with a strong resemblance. Hans Altwies and Geoff Packard (who play Jaws stars Robert Shaw and Roy Scheider, respectively) look the part enough to be believable, while inclusive casting is also used, and powerfully, for several characters: film editor Verna Fields (E. Faye Butler), producer David Brown (Timothy McCuen Piggee), and casting director Shari Rhodes (Alexandria J. Henderson). Butler is a vocal powerhouse and sings her big number with a gusto that is evocative of Judy Garland. Henderson, also in excellent voice, conveys inspiring ambition and confidence.

(© Lindsay Thomas)

The real star here, however, is Spector. Bruce is told through the eyes of Spielberg, who frequently has asides to the audience, both sung and spoken. Though Spielberg's childlike outlook of the world is directly referenced throughout, his passion and excitement are reinforced thanks to Spector's wide-eyed performance. He makes the most of the material with his pure embodiment of the young, unassuming director.

One could argue that this musical has the wrong title. It really has little to do with BrucE itself; in fact, apart from a few drawn designs shown via projections, we don't even see the monstrosity in all its glory, which is a bafflingly missed opportunity. Still, the scenic and projection design shine. The first of the two set pieces (by Jason Sherwood) is a Hollywood Squares-style wall of cubicles featuring six different offices. During the second half, Shawn Duan's glorious projections depict the seaside town of Martha's Vineyard, where Jaws was shot. The wild waves and stormy weather effectively transport the audience and offer a distinct flair, making this part of the show particularly enjoyable to look at (despite an overall visual blandness in Feore's staging).

The fundamental problem with Bruce is not that it is a musical. Oberacker and Taylor are correct in their inclination to musicalize this and Spielberg makes for a compelling lead character. However, with a rushed book and a weak score, it plays like a show still in workshop. It is curious why this musical with a definite two act structure has no intermission, and runs for a mere hour and forty minutes. The conclusion of the story is hastily and unsatisfactorily resolved; we leave knowing the facts about the creatives involved, but there is little emotional resonance.

A longer runtime would solve both the rushed conclusion and most of the character problems, giving room for the story to breathe. As the show comes to end, the writers rely on the overused trope of repeating seemingly "inspirational" lines from earlier that, unfortunately, are never as effective as they want them to be.

And if there is no Bruce to be seen, at the very least, change the title.