Review: Help, Claudia Rankine's Treatise on Race, Is Actually the Cry of a Weary Audience

Delayed by Covid, Rankine’s play finally makes its world premiere at the Shed.

(© Kate Glicksberg Photography)

"I am here — not as I — but as we — a representative of my category — the approximately 8 percent of the U.S. population known as Black women," the narrator clarifies in the opening moments of Claudia Rankine's Help, the TED Talk presently masquerading as a new play at the Shed's Bloomberg Building. As audacious as it is to presume to represent 22 million individuals, this passage succinctly conveys the hubris that passes for wisdom in contemporary academia (Rankine was a professor of poetry at Yale when she started work on Help and has since taken a position at NYU). It also gives Rankine and her audience an opportunity to lay their politics on the table from the outset: During a list of prominent Black women, Stacey Abrams receives rapturous applause, while Condoleezza Rice is met with a golf clap.

April Matthis plays this central role with an appropriate mixture of professorial authority and dour self-reflection. With a mic in hand, she tells us how she set out to discover what white men really think by interviewing her airplane seat partners — the ideal captive audience for the kind of theater Rankine seems to want to create.

(© Kate Glicksberg Photography)

There's the white man on the flight back from Johannesburg who chastises the flight attendant for bringing him two drinks while neglecting to bring our protagonist one, but (to her disappointment) chalks this up to the poor state of service rather than race. And there's the CEO who "doesn't see color," to which the narrator responds by invoking Sojourner Truth at Seneca Falls: "Ain't I a Black Woman?" And there's the interaction with her own husband, a white man who rubs her feet as she, inquisitor-like, attempts to trap him in a heresy: "You're like all the 'woke' white men who set their privilege outside themselves," she says, clearly relishing this sadism.

Help is based on a 2019 article Rankine wrote for The New York Times Magazine, which is a much better read than it is a watch. The stage show performed a few previews in 2020 before the Covid shutdown. Rankine has updated Help to reflect all that has happened since then: the summer of protests that followed the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, the presidential election, and the January 6 insurrection.

She uses these events and her own encounters in the liminal spaces of airports and airplanes as prompts for big questions like, "How much agency does agency have?" and, "I wonder, what is this 'stuckness' inside racial hierarchies that refuses the neutrality of the skies?" Rankine begins to feel like a stand-up comedian on eternal tour, unable to produce new material that doesn't revolve around hotels and airplanes. Although, as you might have discerned from the turgid humorless prose, Dave Chappelle this is not.

(© Kate Glicksberg Photography)

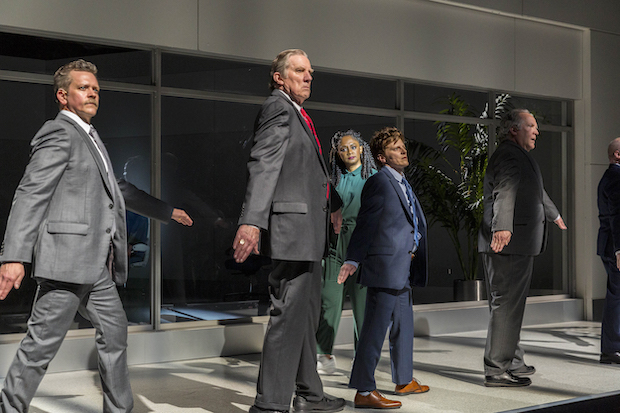

One of the more striking aspects of Help is its sheer extravagance: Under the direction of Taibi Magar, the cast features 11 actors in addition to Matthis, all with character names like "White Man #6" and "White Woman #2." Mimi Lien's set invites us into the theater via the stage, where we can peer through the glass of the world's saddest business class lounge, like some sort of terrarium for white professionals. The barrier later raises like a garage door to allow us to enjoy unfettered views of the swivel chair ballet that constitutes the most interesting part of Shamel Pitts's generically modern choreography. These moments feature lighting (by John Torres) and sound (by Lee Kinney) that might make a Las Vegas producer blush with modesty. It's all set to original music by James Harrison Monaco and JJJJJerome Ellis (who surely fell asleep on the keyboard while listening to his own compositions). The production boasts both an anti-racist coordinator and an intimacy consultant (I suppose for the foot-rubbing). Only a flaming pile of cash could feel more spectacularly decadent.

Despite the high production costs (I won't say "value"), Help joins the ever-expanding buffet of spinach theater — you know it's good for you, even if it leaves a foul aftertaste. And considering the proliferation of such oppressively academic shows, it is safe to assume that a portion of the audience has come to crave that taste in the way some people look forward to confessing their sins and drinking the blood of Christ every Sunday. With her racial theology, Rankine may be offering a necessary service in our increasingly (allegedly) secular society.

(© Kate Glicksberg Photography)

There is the possibility, of course, that the Yale professor speaking to business class travelers about race, writing an article about it for the New York Times, and then mounting a follow-up play in an arts palace named for our billionaire former mayor, only represents the American aristocracy talking to itself, endlessly refining its court rituals as it congeals and separates from the downwardly mobile bulk of the population.

Without ever mentioning "deindustrialization," "income inequality," or "class" (outside the context of airline seating), Rankine tacitly acknowledges this when she notes the rise in "deaths of despair" among white males, and how white men are three times likelier to kill themselves than Black men. But predictably, Rankine ties this back to their own tendency to vote Republican, stating, "whiteness is worth dying for." The conclusion can never be allowed to disrupt the thesis.

Help is a fascinating artifact of an elite culture that prioritizes manners over material well-being, and a liberal ruling class that still hasn't come to terms with its own role in our national disintegration. See it while you can, because its sell-by date may have already passed.