Review: Indigenous Playwright Madeline Sayet Takes On Colonization and Shakespeare in Where We Belong

Sayet’s solo show runs at the Public Theater.

(© Joan Marcus)

Where We Belong, written and performed by Madeline Sayet, is an autobiographical piece that explores Sayet's life as an Indigenous Mohegan woman, in particular her relationships with her family, with her tribe, and, interestingly, with Shakespeare. Sayet has a lifelong fascination with the Public's (and much of the Western world's) favorite playwright, and she entered a PhD program in England to study his work. Over the course of the 80-minute play, she narrates the cultural conflict of being an Indigenous woman studying Shakespeare.

This play and the Public Theater are in many ways a perfect pairing. Long associated with Shakespeare and summer productions of his plays in Central Park, the Public has given Sayet and Where We Belong a platform to acknowledge Indigenous land, the effects of colonization, and the inescapably white, European, male-ness of Shakespeare.

Joseph Pierce, a member of the Cherokee nation, recently wrote that land acknowledgement is not enough — a hollow gesture when not followed up with any meaningful action. By programming Where We Belong, the Public is going beyond land acknowledgement by allocating time, space, and resources to an Indigenous piece that stars an Indigenous actor. What's more, the piece gives a much-needed and likely overdo education to the Public's audiences.

(© Joan Marcus)

Sayet emotionally describes her difficulties at home advocating for better education about the Mohegan people and fighting to keep her tribe's language alive, as well as in graduate school, arguing with professors and being tokenized. In addition to impersonating her various British professors, who try to temper her anti-colonial critiques and can't always understand how Shakespeare and indigeneity intersect, she also speaks as her mother, who can't understand her daughter's love of Shakespeare or a desire to move so far away.

Sayet, though, understands it, and even when she has crises of faith about her chosen path in life, she makes the connections clear for the audience, often through compelling anecdotes. One such moment occurs when she stumbles into a church in England and finds a rock that memorializes Mahomet Weyonomon, a Mohegan chief who traveled to England in 1735 to ask King George II to treat his people better; despite his long journey, he was never given an audience, and died in England while waiting, unable to return home to be buried. In one of the most effective moments of the play Sayet narrates her experience touring the British museum with one of its curators; she expresses disdain at mislabeled Indigenous artifacts and genuine horror at the museum's vast collection of human remains that they refuse to repatriate.

(© Joan Marcus)

Much of Where We Belong is, as the title suggests, about place, land, ownership, culture, crossing borders, and a sense of kinship and belonging. Sayet tells how she was named after a blackbird, one that flies alone, and that she was also destined to be separate — and yet she still felt pulled back to her family, her tribe, her home, and her ancestral land. Sayet's emotional journey is moving and complex, and it is a story that deserves to be heard.

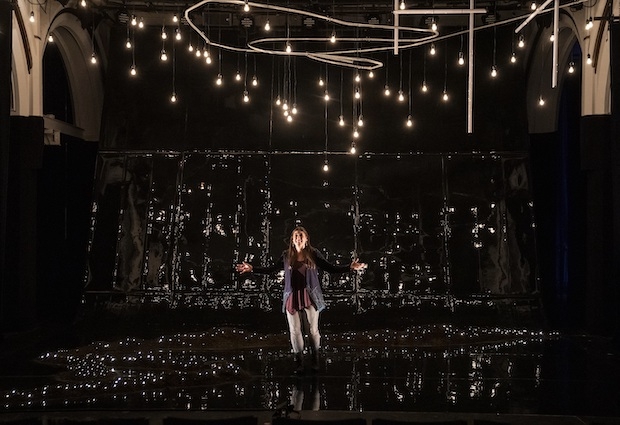

At one point, Sayet describes her experiences being in the audience for two particularly bland TED Talks. Where We Belong itself has the feel of a TED Talk, albeit a long one. While it's beautifully designed by Hao Bai (a trail of life and various light bulbs and bars are all used to gorgeous effect), there is very little stage business to speak of and Sayet appears to be much more of a writer than an actor, and I couldn't help thinking that Where We Belong is less a play than a lecture.

But regardless of the form of this piece, the content and its presentation at the Public are significant. It may not be very theatrical and would be a better lecture than a play, but Where We Belong has great educational value and is extremely thought-provoking, and is thus entirely worth seeing.