Review: Ralph Fiennes Plays Robert Moses as a Shakespearean Villain in Straight Line Crazy

London Theatre Company brings David Hare’s New York drama across the pond.

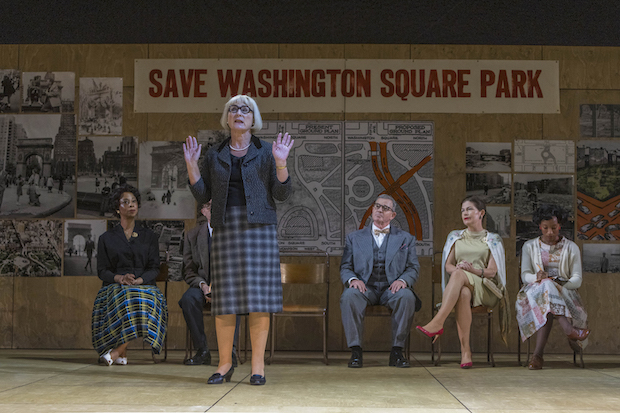

(© Kate Glicksberg Photography)

It’s Robert Moses’s New York — you just live in it. This has been true for much of the past century, and it will likely still be true when you and I are dead. Such is the impact of New York’s master builder and parks commissioner, who planned the major highways in New York City and Long Island, oversaw massive construction projects like the United Nations and Lincoln Center, and once held 12 separate government-appointed posts without ever being elected. His most important role was as head of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, which gave him near-autocratic rule over the bridges and tunnels connecting the five boroughs.

It is perhaps in that undemocratic spirit that David Hare portrays Moses as a snarling Shakespearean monarch in his new play, Straight Line Crazy, which stars an appropriately excessive Ralph Fiennes. Originally produced at London’s Bridge Theatre, this guilty-pleasure romp masquerading as a serious political drama has come home to New York City via the Shed, the crown jewel of a massive westside development that Moses would have adored.

The title of the play comes from a quote Iphigene Ochs Sulzberger (whose family newspaper did more to shield Moses from public criticism than any other publication) gave to Robert Caro for his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography (and brutal indictment) of Moses, The Power Broker, to which the playwright is obviously indebted. Hare puts the line in the mouth of the activist Jane Jacobs (Helen Schlesinger), who merits not one mention in Caro’s book, yet has somehow been immortalized as Moses’s primary antagonist, as she was in the 2017 rock musical Bulldozer. Happily, Straight Line Crazy is a much more enjoyable watch than that ill-begotten project. Like Shakespeare’s best history plays, its dubious account of the past offers a platform for memorably grand performances.

The first act takes place in 1926 when Moses is planning to run a pair of “parkways” (a clever invention to evade existing laws about “highways”) across Long Island and right through the estates of some of the richest men on earth. Henry Vanderbilt (Guy Paul) calls this expropriation Napoleonic and warns of impending anarchy. “No,” Moses corrects, “democracy.”

The second act flashes forward to 1955, when Moses is on the verge of driving a “sunken highway” through the center of Washington Square Park. Jacobs has rallied the people in opposition, but Moses doesn’t much care for democracy at this point. “I’m the dirty bastard who pushed through the things democracy needed, but which democracy couldn’t deliver,” he self-righteously howls. He’s less Caesar leaving the people his private arbors than he is Coriolanus, bequeathing them nothing but disdain and exhaust fumes.

Fiennes plays Robert Moses, and Alisha Bailey plays Mariah Heller in David Hare’s Straight Line Crazy, directed by Nicholas Hytner and Jamie Armitage, at the Shed.

Heller

(© Kate Glicksberg Photography)

Because Moses’s vision for roads and slum clearance involved the mass displacement of poor people of color, Hare gives over a chunk of stage time for a response. It comes from a young Black woman in Moses’s office named Mariah Heller (Alisha Bailey) who tells the boss: “You knocked down buildings full of Puerto Ricans and Mexicans and Negroes, and you did it because to you they weren’t real people. They were just dirt which had to be cleared out the way.” Bailey delivers this imitation Sorkinese with the correct amount of sonorous rectitude, but you have to suspend your disbelief at 30,000 feet to accept Moses standing there and listening to it (or that Mariah would have been hired at Triborough in the first place). Such moments feel more like an exorcism than a historical drama.

When Mariah leaves, longtime assistant Finnuala Connell (a feisty Judith Roddy) takes up the prosecution. We’re meant to believe that she’s worked for Moses for three decades (her entire adult life), but she’s willing to risk it all now, so inspired was she by Mariah’s bravery. As a dramatist, Hare flatters his audience (“But now he’d taken on a far deadlier enemy – the one no one ever beats…the middle classes”) while simultaneously insulting their intelligence.

(© Kate Glicksberg Photography)

Co-directors Nicholas Hytner and Jamie Armitage compensate for the deficiencies of the script with a nimble staging that never gives the audience enough dead air to really consider what we’re hearing. Bob Crowley’s set flows on and off the empty thrust stage with the actors, costumed, also by Crowley, in period-appropriate outfits. Composer George Fenton occasionally underscores a monologue with cinematic music, but these moments are light and unobtrusive to the forward motion of the plot.

By keeping the production out of the way, the directors serve the audience something that never goes out of fashion in New York: British actors chewing the scenery. The performances are as outrageously luxurious as a full-length fur coat, so much so that it’s easy to ignore the wire hanger on which they hang.

Fiennes wears his stiffly, as if he’s always prepared for a candid photograph. He chews his consonants and stretches his vowels like an American carnivore. It’s hard not to giggle at some of his more over-the-top pronouncements. “I’ll be out to see where the Bergen County Expressway should be. And the Throgs Neck Expressway. And the Clearview Expressway,” he hisses as if delivering a curse — which is exactly what these clogged arteries are for Tristate motorists.

(© Kate Glicksberg Photography)

No actor is having more fun than Danny Webb as Governor Al Smith. Chomping on a cigar, swilling bourbon, and spilling political wisdom, he’s like the love child of George Burns and Yoda. Moses is the sun around which this entire play orbits, but when Smith enters the room, the center of gravity suddenly shifts. Without telling us, Webb shows us how important executive support was to Moses.

For all his interest in American politics (he is also the author of the Iraq War drama Stuff Happens), Hare breezily ignores the forces that sustained Moses’s power: his network of patronage, his support from construction unions, and crucially, his ability to deliver lavish returns to Wall Street through authority bonds — which naturally created demand for more construction projects and more bonds. Perhaps it is too much to ask of any dramatist to convey such technically complex subjects, but Hare doesn’t even try, tying everything back to personality. I suspect that tendency is what allowed Moses to get away with as much as he did in a state where most eligible voters abstain courteously.