Review: Robert Icke Does Justice to the Oresteia While Updating It to Modern Times

Icke’s take on Aeschylus’ three-play Greek tragedy, starring Anastasia Hille and Angus Wright, makes its North American premiere at the Park Avenue Armory.

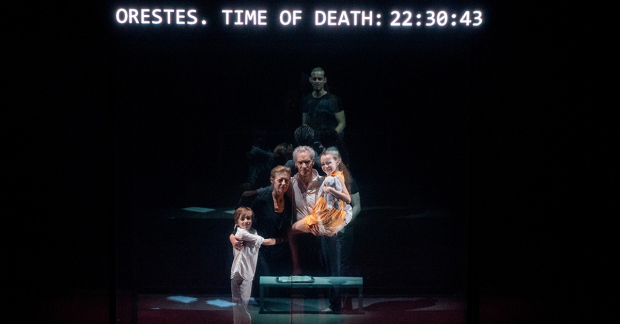

(© Stephanie Berger)

Reading Aeschylus' Oresteia for the first time in preparation for the Robert Icke-directed production that opened on Tuesday evening at the Park Avenue Armory, I was astonished at how relevant its epic vision of politics and human nature still felt. Even way back in the 5th century BCE, Aeschylus, in this legendary trilogy of plays, displayed a startlingly clear-eyed view of how vengeance begets vengeance across generations, how fickle the winds of popular sentiment can be, and how much compromise would be needed to form a democracy. One could present the entire trilogy straight, without too much modern updating, and it could still make a considerable impact.

That is not how Icke is presenting it, however. Instead, his Oresteia (alternating in repertory with his Hamlet, which was previously reviewed here) is a very free four-act adaptation "after Aeschylus" — which, in performance, comes off as an equally grand extrapolation of the major political, religious, and human themes of Aeschylus' original to suggest how they might play out in contemporary times.

I say "suggest" because, given his preference for muted modern dress and chilly minimalist scenery (Hildegard Bechtler's set and costume design are awash in shades of dark blacks and gleaming whites that Natasha Chivers's lighting design gives a sleek veneer to), Icke refuses to push any topical connections too hard. Though his production features characters giving press conferences and modern-style courtroom trials, it still retains a certain timeless, even ritualistic atmosphere (that latter quality intensified by Tom Gibbons's wall-to-wall sound design, which underscores even standard dialogue scenes with a vaguely spiritual hum).

Beyond dispensing with Aeschylus' verse, Icke's most daring departure from the text is to devote most of his first act to Agamemnon's (Angus Wright) sacrifice of his daughter Iphigenia (played by Alexis Rae Forlenza at the performance I attended; she alternates with Elyana Faith Randolph), which eventually motivates his wife, Klytemnestra (Anastasia Hille), to murder him in the second act of Icke's version.

This first act is inspired not by Aeschylus, but by Euripides's Iphigenia in Aulis — and it turns out to be the evening's most emotionally powerful stretch. As Agamemnon, Wright burns with agonized ambivalence over what he believes is a filicide mandated by godly prophecy, while Hille sets the stage alight with thunderous anger and indignation when her husband divulges the prophecy to her. Both actors bring heft to Icke's interest in exploring the moral calculus that comes with considering the individual versus the greater good.

The rest of the three-and-a-half-hour production pales a bit in comparison with that searing first act, but that may simply come down to Icke treading familiar territory, at least for those who know the Aeschylus original going in. There are still plenty of imaginative touches to admire throughout. In Icke's version, Agamemnon returns from the years-long war in Troy that resulted from his familial sacrifice less a conquering hero than a broken, PSTD-stricken man — which makes Klytemnestra's bathtub murder of him even more gut-wrenching, especially when she explodes in near-orgasmic fervor afterwards. Icke also has Wright play Klytemnestra's new lover Aegisthus, whom Agamemnon's son Orestes (a sensitively anguished Luke Treadaway), inspired by sister Electra (a mournfully resolved Tia Bannon), targets in addition to his mother in his revenge for his father's killing — thus reinforcing a sense of the cycles of vengeance perpetuated throughout history. That, along with timers that are projected on LED screens onstage before the show and during intermissions, infuses the whole production with a sense of tragic destiny.

Not all of Icke's changes pay off. He has saddled his version with a therapy session-like framing device in which Orestes recalls much of these events to a psychologist (Kirsty Rider). That's not a problem in and of itself, but the set-up leads to a climactic third-act reveal about Electra that is the production's one questionable change from the source material (though one's mileage may vary as to the effectiveness of Icke's menacing use of the Beach Boys' "God Only Knows" in Act 1).

The production rallies, though, with a fourth act that finds startling relevance in Aeschylus' depiction of the formation of the rule of law, one that subtly ties to questions that have popped up afresh in the wake of the US Supreme Court's striking down of Roe vs. Wade. It's a satisfying cap to a remarkably intelligent new take on the Oresteia, one that will have audiences marveling afresh at the social, political, and historical insights that Aeschylus still has to impart to a new generation.