Review: The Visitor Makes an Unwelcome World Premiere Off-Broadway

Tom Kitt, Brian Yorkey, and Kwame Kwei-Armah adapt a 2007 film about oppressed immigrants into a musical.

(© Joan Marcus)

Can the old coexist with the new? Can the well-established make space for newcomers without fear? And do those old-timers have something to offer the newcomers, while also learning something themselves? These questions hover over both the onstage and offstage story of The Visitor, the sweet and sad — and ultimately disappointing new musical at the Public Theater.

It's based on Thomas McCarthy's 2007 film and features a score by Tom Kitt and Brian Yorkey, the team behind Next to Normal. Yorkey and Kwame Kwei-Armah have adapted McCarthy's screenplay for the stage under the direction of Daniel Sullivan. It retains the basic skeleton of the plot while stripping away much of the flesh that made McCarthy's film so very human.

(© Joan Marcus)

The show opens with Walter (David Hyde Pierce), a widowed economics professor at the University of Connecticut, listlessly lecturing his students on Keynes. A frown in a gray suit, he is the embodiment of exhausted liberalism — stricken by loss and the creeping notion he has nothing left to offer. A reluctant work trip to New York City changes all that.

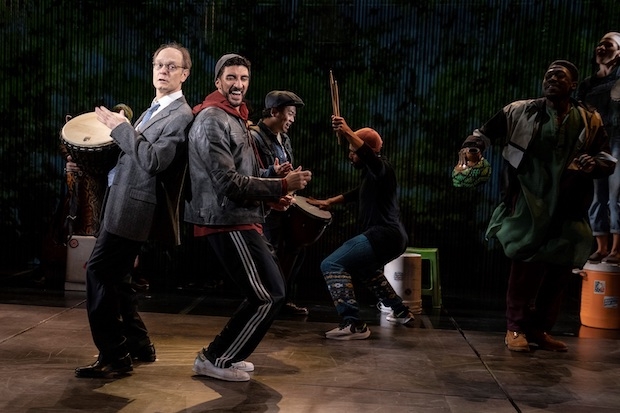

When Walter enters his pied-à-terre, he is surprised by Tarek (Ahmad Maksoud) and Zainab (Alysha Deslorieux), a young couple who rented it from someone named Ivan. He's a drummer, and she sells jewelry. Both are immigrants who have already moved seven times this year. That this illegal sublet — to a drummer — has not raised the ire of the co-op board is the most fantastical part of the story.

Instead of calling the police, Walter takes up the churlish challenge hurled by so many nativists and actually invites them to stay until they secure a new place. In return, Tarek teaches Walter how to play the drum. Not long after, Walter hires a lawyer to help free Tarek from ICE detention after he is erroneously arrested for hopping a subway turnstile (another leap of imagination in 2021, although the script is never clear on what year we're in).

(© Joan Marcus)

While the film is set in a definite time with clear stakes (in the wake of 9/11, inside Michael Bloomberg's model fascist state), the musical is fuzzier in its storytelling. And even in its blurriness, that story feels mismatched with its form. Kitt and Yorkey seem to want to write the next The Band's Visit, translating the subtle seduction of independent cinema into musical theater. Unfortunately, they do nothing to retrofit their overwrought emotive style to this task. The result is a soaring and forgettable score that regularly finds the story paralyzed in the path of an oncoming glory note.

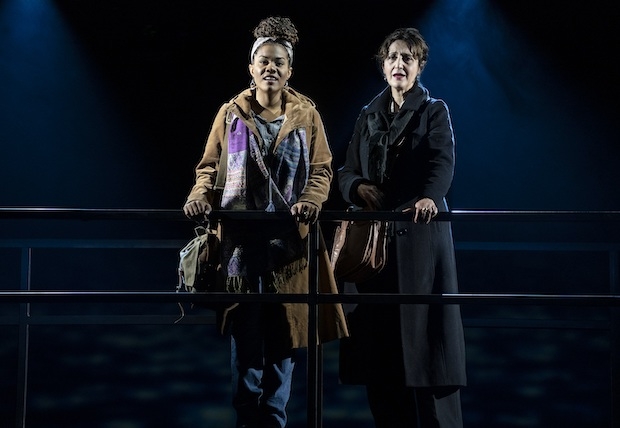

None of this is the fault of the cast, all of whom work overtime to keep us from noticing the gaping holes in the plot. Maksoud is utterly charming as Tarek, deploying a broad smile and instant ease that helps us understand how he and Walter become quick friends. Deslorieux is the opposite, guarded and moody, wordlessly conveying a history of exploitation that has led Zainab to trust no strangers. As Tarek's mother, Jacqueline Antaramian gets the closest to capturing the tone of the film in her quietly heartbreaking performance. Meanwhile, the ensemble vividly portrays the living, breathing city around them (Lorin Latarro's muscular choreography is the most vital part of the staging).

(© Joan Marcus)

Pierce once again shows why he is one of the greatest stage actors of our time by bringing warmth, depth, and empathy to a script that is short on all three. "Stay at my apartment," he abruptly offers Tarek and Zainab, immediately turning toward the audience with a look of confusion, as if he cannot quite believe he said it either. We instantly accept this clunky moment through the force of his relatable awkwardness. Unfortunately, not even Pierce can sell "Better Angels," a #resistance Facebook post masquerading as an 11 o'clock number.

Sullivan's production is sleek and polished: The metallic simplicity of David Zinn's set reminds us of the looming threat of detention, a pale streak of light slashing across its corrugated surface representing hope (lighting by Japhy Weideman). Toni-Leslie James costumes the ensemble in knitwear and coats, letting us know that the city is getting colder and meaner. A brief sound cue (by Jessica Paz and Sun Hee Kil) immediately transports us to the Staten Island Ferry.

Yet not even this crack design team can overcome the fundamental contradictions in The Visitor: Makeshift plastic drums with "Obama '08" and "Black Lives Matter" stickers slapped on them betray a desperate effort to marry professional-class liberalism with the demands of a younger radicalism that has no patience for vague promises of "hope and change."

(© Joan Marcus)

Squaring this circle would be difficult under the best conditions, but The Visitor has been through a troubled creative process: Originally slated to begin performances March 2020, it was postponed due to the pandemic. It lost one of its original principals a week into previews, which had already been delayed a week to respond to issues concerning race, representation, and identity.

Reports have described this as "de-centering whiteness," which seems like an impossible task when the protagonist with the most defined emotional arc in the source material is a middle-aged white man who gets his groove back through a close encounter with immigrant tragedy. This may not be the story the creatives are interested in telling anymore, but it's the one they chose when they began developing the musical.

Attempting to salvage what they have while tossing a bone to newly woke sensibilities, the creators of The Visitor have forged an unsatisfying compromise. This might be an essential task in politics, but it is usually deadly in art, as it is here. In its current form, The Visitor exudes all the forced joy and insincere fellowship of a Democratic Party rally in the 2022 midterms.