Searching for Proof of Love in Your Husband's Text Messages With Another Woman

Chisa Hutchinson’s solo show is the first new play commissioned by Audible.

(© Joan Marcus)

Sometimes life leaves you with a cliffhanger that can never be satisfied. Is it better to make peace with that uncertainty, or come to a conclusion based on faith? That's the dilemma faced by the protagonist of Chisa Hutchinson's Proof of Love, now making its world premiere at Minetta Lane Theatre as the first commission from Audible's Emerging Playwrights program. Brimming with intrigue and insight, it's an auspicious start to an exciting theatrical venture.

This 70-minute monologue is told entirely from the perspective of Constance Daley (Brenda Pressley), a well-to-do black woman visiting her husband Maurice in the ICU. Comatose and hooked up to a ventilator, Maurice landed in this sorry state after surviving a car accident on the way to play cards with his friend Harry — or so Constance thought. The location of the crash was miles off the route to Harry's. Her initial suspicions are confirmed when she unlocks his phone and discovers evidence of a years-long affair between Maurice and a 44-year-old city permits clerk named Lashonda. She calmly shares her findings on the other woman and her family: "Three children — two boys and a girl— ages 17, 15, and 12," she says as she crosses her legs, flashing the red soles of her Louboutins. "All by the same father. Surprisingly."

(© Joan Marcus)

In Constance, Hutchinson paints a compelling portrait of a certain kind of upper-class black American: mindful of status and eager to separate herself from the poor. She wonders if Maurice's attraction to Lashonda stems from his own working-class upbringing (he clawed his way from the projects to suburban splendor). She also wonders how her woke daughter, a graduate of Howard University (even though mom favored Vassar), will respond to learning about her father's affair: "She'd probably throw a fish-fry or a cook-out, some distinctly black celebration replete with line-dances and purple drank," she muses, taking out her rage on a hard "k."

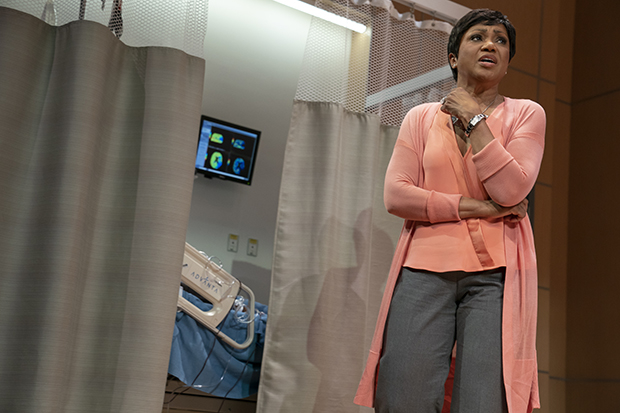

With every folded arm and icy observation, Pressley embodies a character that Hutchinson calls "as close as you can get to a WASP while being black." Her crisp diction provides kindling for a slow-burning disdain toward Lashonda and her ilk, while her stereotypical voice for Lashonda is glazed with attitude. Yet by showing us Constance's vulnerability, Pressley prevents her from coming across as an irredeemable classist: Her biases are born of insecurity more than anything — and anyone would feel insecure in her admittedly pricey shoes.

Director Jade King Carroll complements (but never overwhelms) Hutchinson's script with high production values. Alexis Distler's set depicts Maurice's hospital room, its privacy and unreasonable spaciousness indicating not just the family's considerable wealth, but the vast solitude of Constance's situation: Keeping this secret is a burden, but telling anyone would be an admission of defeat. Jen Caprio outfits her like she just stepped out of a spread for Martha Stewart Living, a knee-length cardigan over an elegant peach blouse. Justin Ellington punctuates her anxiety with the whirring sound of Maurice's ventilator, the aural evidence of his persistence when he can no longer speak for himself.

(© Joan Marcus)

For a character whom we only ever hear struggling to breathe from behind a hospital curtain, Maurice emerges in vivid detail. As Constance describes his romantic wedding proposal, we find ourselves falling in love with this gentle yet hungry individual, a man with as many secrets as charms. Constance's unwavering love and admiration for him makes his betrayal all the more devastating — but also surmountable. Proof of Love is one of the more realistic portrayals of infidelity I've seen onstage, and its observations on love and marriage are spot-on. That bodes well not just for this play, but for a thrilling dramatic experiment that invites audiences into the theater, but also invites them to enjoy plays on their morning commute.