Seeing Is Believing in Shakespeare in the Park's Othello

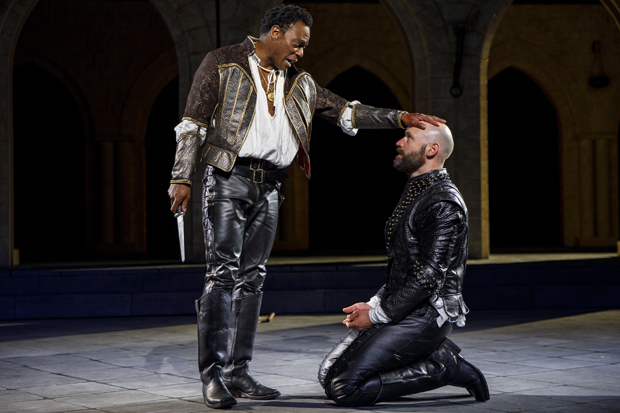

Chukwudi Iwuji and Corey Stoll star in Shakespeare’s tale of love and jealousy.

(© Joan Marcus)

Racist interpretations of Shakespeare's Othello have cast the title character as a hot-tempered barbarian easily manipulated by the crafty Venetian Iago. But this is untenable in the 21st century, with most productions highlighting racial discrimination against Othello, as if this is the only thing that matters in a play about jealousy, trust, revenge, and love. Director Ruben Santiago-Hudson is having none of it. He thrillingly rejects facile one-dimensional approaches, reaching for and grasping something meatier and a whole lot more challenging.

Othello (Chukwudi Iwuji) is a Venetian general of Moorish (North African) origin. He has recently eloped with Desdemona (Heather Lind), daughter of the senator Brabantio (Miguel Perez). After some initial consternation, Dad accepts the marriage as Othello prepares to sail off to defend Cyprus from a Turkish invasion. This match enrages Roderigo (Motell Foster), who wanted Desdemona for his wife. Othello's deceitful ensign, Iago (Corey Stoll), sees an opportunity in all of this: He hates Othello and thinks that if he can make the Moor believe that Desdemona is unfaithful, he can lead him down a path of destruction. The presence of Othello's handsome yet credulous captain, Cassio (the ideally cast Babak Tafti), is sure to aid him in this plot.

(© Joan Marcus)

Santiago-Hudson has successfully led his cast to performances that make all of these characters complicated, contradictory, and fully human. That begins with Othello: Far from an irrational brute, Iwuji portrays a military man ahead of his time. Although his profession is killing, he melts into pure tenderness when he so much as glances at Desdemona. Acting with the decisiveness of a general and demanding "ocular proof" of any claim, he puts his confidence in empirical facts over faith. Yet once he has enough to form a theory (especially about something as precious as love), he eschews all conflicting evidence, irresistibly sliding into paranoia and rage.

Armed with a bundle of circumstantial evidence and alternative facts, Stoll's Iago is confident, funny, and relaxed, making us understand why so many characters view him as a trusted source. He's not driven by pure malice but by his own irrational jealousy. Rather than being Shakespeare's most inexplicable evil villain, Iago à la Stoll is as clear about his motivations as he is deliberate in his machinations.

While these two men typically consume all the air in Othello, Alison Wright gives a standout performance as Iago's wife, Emilia. With a confident gait and twisted grin, Wright ferociously embodies a woman strong enough to push back against her odious husband. It's no surprise that the men of the play leave her to die alone, perhaps relieved by the passing of such an inconveniently outspoken woman.

(© Joan Marcus)

By contrast, Lind's Desdemona is the model of feminine submission, helplessly yielding to her husband's madness through the very end. Toni-Leslie James costumes her in an opulent dress with sleeves that look like ribbons tied into bows, a gift for Othello to unwrap and covet.

Santiago-Hudson has set Othello during the period Shakespeare originally envisioned: The spectacular use of brocade and velvet in James's costumes places the story squarely in the 16th century, the time of Venetian rule on Cyprus. Taking full advantage of the remarkable width of the Delacorte, Rachel Hauck's set suggests a Mediterranean fortification with gothic arches, a hallmark of the merchant empire that for centuries served as a crossroads between East and West. Jane Cox's dazzling lighting flickers like torchlight under the faux limestone, while Jessica Paz expands the world further by tantalizing us with sounds seemingly from beyond the theater.

In the production's one major misstep, Derek Wieland's synth-heavy original compositions attempt to capture the "shrill trump" and "spirit-stirring drum" of Othello's military glory, along with Desdemona's maiden-in-a-tower melancholy. Unfortunately, they end up sounding like the ambient music of a 1990s video game — more MIDI than medieval.

(© Joan Marcus)

Luckily, it doesn't much detract from Santiago-Hudson's timely production. This Othello unnervingly casts doubt on the inviolability of "ocular proof," especially when we view that proof with less than clear eyes. Santiago-Hudson also makes a strong argument for Othello as a prescient challenge to the empiricism of Elizabethan thinkers like Francis Bacon. Are humans actually capable of approaching the truth with objective eyes when we're all products of subjective pasts? It's a question that cannot be asked enough as we place our trust in video and photographic evidence that is becoming increasingly easy to doctor. Seeing may be believing, but that's a frightening thought when all we see are lies.