Sojourners and Her Portmanteau

New York Theatre Workshop produces two plays from Mfoniso Udofia’s nine-play cycle about the Nigerian-American experience.

(© Joan Marcus)

Can a family hold together across borders? This unspoken question menacingly hangs over the repertory presentation of Mfoniso Udofia's Sojourners and Her Portmanteau at New York Theatre Workshop. While some people might cling to the comforting cliché that blood is thicker than water, the more clear-eyed will ask if it is even desirable to maintain a close bond with people whose values and lifestyles diverge dramatically from one's own. Udofia offers no easy answers, but her firm grasp of family dynamics will give audiences much to consider in this rich slice of what promises to be a much larger pie.

Sojourners and Her Portmanteau are two chapters in an ambitious nine-play cycle (much of which is yet unwritten) following four generations of the Nigerian-American Ufot family. Sojourners made its world premiere with the Playwrights Realm last January (the company is credited as an associate producer here) in a production that was as notable for its emotional truth as its unapologetic embrace of magic.

(© Joan Marcus)

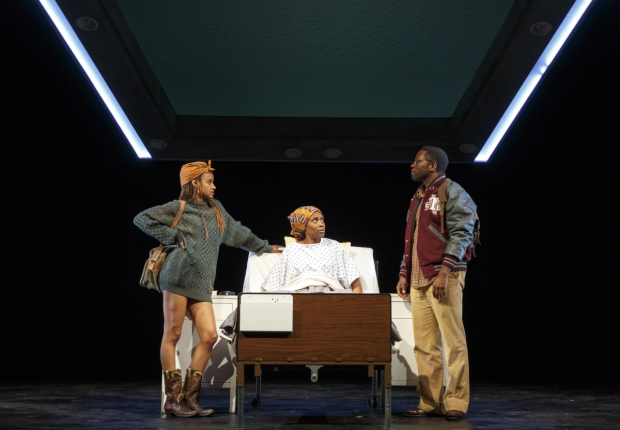

Director Ed Sylvanus Iskandar retains the original cast and creative team from that outing, but has refined his approach to the story: Sojourners introduces us to married couple Abasiama (Chinasa Ogbuagu) and Ukpong (Hubert Point-Du Jour), both living in Houston circa 1978 as foreign students. Abasiama manages to keep up with her biology studies while working the graveyard shift at a gas station. She's also eight months pregnant. Ukpong is far less disciplined, disappearing for days at a time to dance and attend protest rallies. He is absent when Abasiama goes into labor, so her hooker friend Moxie (Lakisha Michelle May) takes her to the hospital with the help of Disciple (Chinaza Uche), another Nigerian student with an eye for Abasiama.

Her Portmanteau takes place 30 years later. Abasiama (Jenny Jules) has two adult daughters: Adiagha (Ogbuagu) lives in New York City. Iniabasi (Adepero Oduye) has just arrived from Nigeria, hoping to finally forge a new life in the States. She was promised a room in Abasiama's expansive home in suburban Massachusetts, but she's bunking with Adiagha because of a sudden flare-up of family politics. Can a one-bedroom apartment hold all that simmering resentment?

(© Joan Marcus)

Oduye is a master of the icy glare that says a thousands words. Rather than making her feel closer to her American relatives, Facebook has merely reinforced Iniabasi's perception that she was given the raw end of the deal when her parents decided to have her raised in the old country. Adiagha's Ikea showroom of a dwelling (complete with a million throw pillows) does little to disavow her of that notion. Theatergoers may recognize Adiagha's furniture as down-market, but it sure beats a busted flat in Lagos. The fact that Adiagha treats so many of her belongings as disposable makes things worse.

The only member of the cast appearing in both plays, Ogbuagu delivers a performance to remember: Her portrayal of Abasiama in Sojourners is as noble as ever as she struggles to carry the weight of the world on her own. Ogbuagu is practically unrecognizable in Her Portmanteau, adopting a distinct physicality and speech pattern. Still, elements of Abasiama appear on Adiagha, like a hand-me-down sweater from mother to daughter.

Iskandar has led this six-person cast to finely crafted performances: The sojourners of the first cast have settled into their roles more comfortably, with choices pruned back to better resemble real life. The three women of Her Portmanteau sustain a thick air of tension through a play that is mostly one long scene. Jules does an especially good job of projecting a character we've already met into the future, fully developing the confidence and presence that was just beginning to bloom as the last play ended.

Scenic designer Jason Sherwood keeps the rotating stage from the Playwrights Realm production, but has lifted the walls in what was formerly a revolving house. Set pieces and actors easily glide on and off, allowing Iskandar to better activate transitions: Abasiama stands in the center of the stage as her life spins around her. A giant ceiling with recessed lighting hangs over the stage, which lighting and projection designer Jiyoun Chang lights to more fully suggest each new space. Jeremy S. Bloom's retro sound design creates the perfect emotional underscoring for each scene. He stealthily introduces music through onstage radios or the stereo of a neighboring apartment seeping through Adiagha's paper-thin walls, keeping the realism of the piece while giving it a cinematic quality.

(© Joan Marcus)

Udofia's story may be about a Nigerian-American family, but electronic communication and relatively cheap international travel are making families like the Ufots increasingly common. Distance is no longer a barrier to a family relationship, but the problems of jealousy, suspicion, and disappointment still remain. Udofia unpacks those issues with uncommon sensitivity and brimming imagination.