Staying Power and the Power to Leave (Part II)

Why a critic can — but mostly shouldn’t — walk out at intermission.

This is part II of Michael Feingold's latest "Thinking About Theater" column.

Click here to read part I.

At movies, comings and goings during the film are a frequent part of the experience. "The running time is 97 minutes," the critic Kenneth Tynan once said of a film. "The walking-out time is much earlier." The old days of "continuous performances" bred a habit of arriving late for a film, knowing that you could catch the beginning when the next show started. Even in today's more regulated world, departures and returns — for popcorn and soda, or for bathroom breaks — remain a constant, on a par with texting as a guaranteed irritant to those actually trying to pay attention to the film.

The theater, where you're discouraged from coming and going (as indeed from texting) during the performance, has different parameters: The actors in a film can't see you if you get up to leave during their performance, and they'll never notice the empty seats you vacate during an intermission. Actors onstage can't help but be aware of such things, which don't improve the spirit in which they approach their work.

The press, to which producers generally grant good seats in a noticeable section of the theater, has to take this reality into account, and feel a sense of obligation not only to the management as their hosts but to the actors as fellow human beings and, in a sense, colleagues. It's bad enough that, more often than not, you're likely to write something less than enthusiastic about a show — doing which is pretty much the equivalent of telling proud parents they've given birth to an ugly baby. To add the insult of leaving early to the injury of critical carping or negative reporting hardly makes sense.

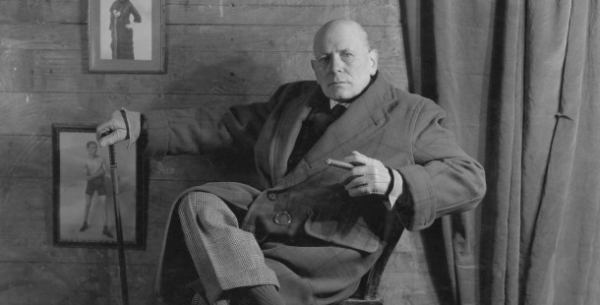

Yet there are times…If a show is so infuriating that you can't possibly sit through it all without writhing or moaning, you should definitely leave, at an intermission or other discreet moment. If it's so overmasteringly dull or hopeless that no improvement is possible, an intermission exit is clearly indicated. The issue then becomes what sort of reviewing or reporting you feel qualified to do about it. James Agate, the brilliant critic of the London Sunday Times during the 1920s and '30s, was once caught by the producers of a British musical making his way home at intermission on the show's opening night. "Gentlemen," he said firmly, in response to their cries of protest, "you don't have to drink an entire barrelful of bilgewater to know that it's bilge!"

Thinking back on the very few performances from which I've skedaddled at intermission over the past four decades — I don't think they add up to more than half a dozen — two or three of them fit Agate's description. Musical barrels full of bilgewater, they were clearly d.o.a., in a manner so hopelessly drab and laborious that there wasn't the slightest chance of either their miraculously waking up or their sinking into jaw-dropping absurdity after the break. I also felt fairly sure, since I wrote for a weekly, that they wouldn't survive long enough for my review to make any difference.

So I can't tell you, for instance, what happened in the second act of the musical Marlowe (1981). I only recall that nobody who stayed to the bitter end ever said to me that I had missed something spectacular. When a musical is a spectacular disaster, the press inevitably wants to stay, to gauge its magnitude. I sat in flabbergasted bemusement through every minute of Rockabye Hamlet (1976). Talk about jaw-dropping — my jaw hit the floor so often that night I wasn't sure I could ever shut it again. (Having since then become notorious for never keeping my mouth shut, I put the blame wholly on the second act of Rockabye Hamlet.)

Since I've spent a lot of time covering shows that aren't traditionally structured, I've sometimes found myself up against works whose form made sustained attention a special challenge — exceptionally lengthy image-theater pieces that seemed to offer no prospect of development, only an endless onward plod of images — more installations than theater event. In the Stoned '70s, such pieces often ran for hours, encouraging an audience response more like milling about at a party than attending a dramatic opus. Leaving a party early is easy enough, and like a well-behaved guest, I would usually explain in my review (the critic's equivalent of a bread-and-butter note) what had motivated my leaving.

Finally, I must confess that I did, once, walk out on Wagner's Die Meistersinger at the Met. I don't feel particularly guilty about this. I had seen the production before, and the cast on that particular night was full of replacements and singing less than brilliantly. And I am not sure that even brilliant singing could make me love Die Meistersinger. It seems to me an opera built for walking out of, the epitome of the old wisecrack that "a German joke is no laughing matter." I have sat through many operas, including other Wagner operas, since then, and written about a few. I don't feel that this tiny instance of disloyalty, or any of the others, has appreciably injured my standing. At times — and Wagner is a great maker of such times — the work itself seems to offer a virtual invitation to leave.

Robert Benchley, the great humorist who was the New Yorker's drama critic in the 1920s, famously took up one such invitation offered by a play called The Squall, in which many of the characters were Slavic migrants who spoke a pidgin English, invented by the author, that increasingly got on the reviewers' nerves. Benchley muttered that if one more pidgin-speaking migrant showed up, he would leave. Just then the ingenue dashed on, declaring, "Me good girl. Me stay here." Benchley rose from his seat. "Me bad boy," he stated. "Me go home."

Michael Feingold's next two-part "Thinking About Theater" column will appear on consecutive Fridays January 16 and January 23.