The Lehman Trilogy Mythologizes a Doomed Investment Bank

Stefano Massini spins the fable of Lehman Brothers at Park Avenue Armory.

(© Stephanie Berger)

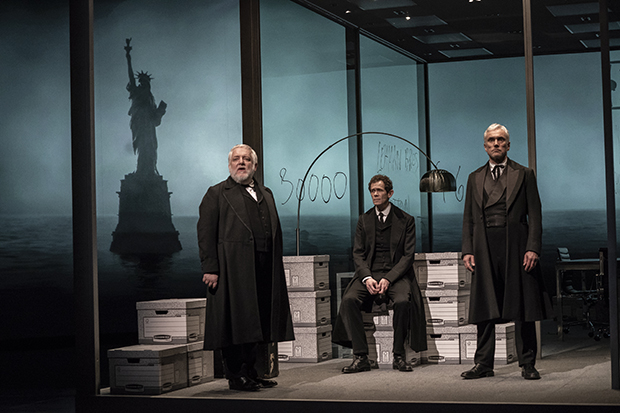

A silhouette of the Statue of Liberty appears in the cyclorama behind the set of The Lehman Trilogy. We recognize the crown and torch, but the figure is different —wraithlike and forbidding, holding out both the promise and peril of America. Stefano Massini explores both qualities in his banking epic, The Lehman Trilogy, about the defunct investment bank Lehman Brothers. Ben Power has adapted it from the original Italian, and Sam Mendes directs. Following its world premiere with London's National Theatre, it now arrives in the city where Henry Lehman always intended to settle: New York.

Finally home, The Lehman Trilogy is playing the biggest venue in town, the Park Avenue Armory, which occasionally feels too big for this intimate drama for just three actors. At times, however, it seems that even the Armory's massive drill hall cannot contain the magnitude of the firm's 150-year existence, which is as dramatic and bloody as any Shakespeare history. In three parts, Massini and Power show how one extraordinary family arrived in America just in time for it to transition from upstart backwater to global superpower.

(© Stephanie Berger)

It starts with the original Lehman trinity. Jewish Bavarian brothers Henry (Simon Russell Beale), Emanuel (Ben Miles), and Mayer (Adam Godley) arrive in America in the 1840s and head straight for that city of dreams: Montgomery, Alabama. Their dry goods store soon becomes a successful cotton brokerage, and Emanuel opens an office in New York in the pursuit of ever-bigger markets and investments. The firm survives the Civil War and a second generation takes over with Emanuel's coldly capitalist son, Philip (Beale), and Mayer's liberal Democrat son, Herbert (Miles). The Crash of '29 ushers in a third generation with Philip's son Bobbie (Godley), who founds the trading department with Lew Glucksman (Miles), moving the firm's profit center away from tangible American industry and into paper-pushing. The resulting bankerdämmerung of 2008 is still fresh in our memories.

Massini and Power rush through that last chapter, perhaps concluding that it is well-trodden territory. Instead, The Lehman Trilogy is one family's tango with the American dream. It's an inspiring immigrants' tale about arriving in America with nothing and becoming fabulously wealthy by trading a product made through slave labor, then profiting on war, and then developing the modern concept of consumer capitalism. Lehman undeniably helped to make America richer, but did it make us better? Massini and Power leave us to debate that after the show.

(© Stephanie Berger)

This play's origin as a radio drama is evident by the way the performers narrate much of the story directly to the audience, an often distressing negation of the dramatic form that actually works well in a play like this, when there is so much ground to cover.

It helps that there are three incredibly skilled actors driving the story. Beale, Miles, and Godley easily slip into new characters through instant changes of dialect and posture. We always know whom they're playing, but they just as quickly snap back to the three brothers, who recount Lehman's tale like souls fated to relive their mortal legacy in purgatory.

Adding to the play's mythic qualities, Massini indulges in flights of magical realism, like the insistence that it never stopped raining for the duration of the Great Depression (try telling that to the Joads), or the notion that Bobbie Lehman lived to be 140 years old and died doing the Twist. It's like something by Gabriel García Márquez, if the friend of Castro had actually understood anything about capitalism.

(© Stephanie Berger)

This grand mythology of banking might seem ridiculous if not for the steady and deceptively simple direction of Sam Mendes, who creates a three-hour-20-minute spectacle with just three performers wearing variations on the same costume (handsomely flared black frocks by Katrina Lindsay). This is not counting an extravagant final tableau featuring 15 supernumeraries, which is the kind of thing one only ever sees at a place like the Armory.

Es Devlin's set is a rotating glass box representing a floor of Lehman's Manhattan office. A man packs files into bankers' boxes in the opening scene, taking place in September 2008. He turns out the lights and the ghostly Henry emerges from the darkness, the first brother to reach the new world (designer Jon Clark creates magic and wonder with fluorescent recessed lighting). The actors stack Devlin's bankers' boxes like blocks to create a variety of set pieces not covered by the sleek office furniture. Nick Powell's subtle sound design and original piano compositions (performed live by Candida Caldicot) fill in the rest.

(© Stephanie Berger)

Luke Halls's elegant projections on the cyclorama behind the set show the cotton fields of Alabama, as well as the ever-growing Manhattan skyline. Halls collaborates with Devlin to make the spinning of the set all the more arresting, and sometimes nauseating. Here, money really does make the world go around, sometimes at a dizzying speed.

The ending of The Lehman Trilogy feels rapid and disorienting, but so did the actual end of Lehman Brothers. It took 158 years to become one of the biggest financial firms on Earth, and less than a week to implode spectacularly. The Lehman Trilogy captures the splendor of the American dream; and like all good dreams, it ends with a rude awakening.