(© Joan Marcus)

Ida Armstrong carries herself like a distant Rockefeller cousin: a social butterfly who can make small talk and new friends in almost any situation. Unfortunately, she also has a tendency to spend like a Rockefeller, a real problem considering her assets are firmly in the red after a life that has lasted a lot longer than she anticipated. Ida is the focus of Max Posner's The Treasurer, now making its world premiere at Playwrights Horizons. Posner dramatizes this all too common scenario with style and sensitivity, leading us to think about our own lives with uncommon clarity.

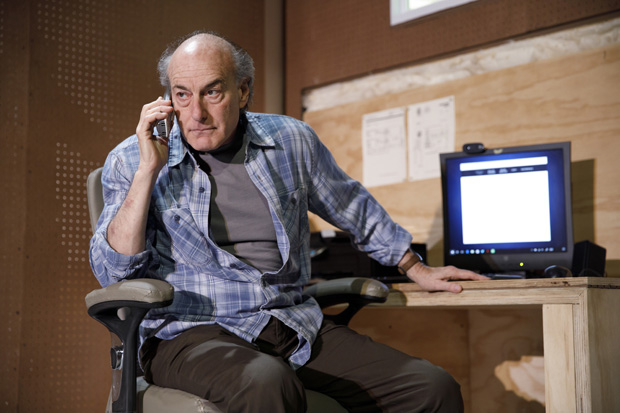

The title of the play is how our protagonist (simply called "The Son" and played with no-frills candor by Peter Friedman) thinks of himself in relation to his mother, the aforementioned Ida (theatrical force of nature Deanna Dunagan). He doesn't love her or even particularly like her, but he understands that he has a fiduciary responsibility to his aging mother as she slips further into dementia. It's a duty made difficult not only by emotional, but physical distance (she's in Albany, New York, and he's in Denver). Still, his siblings (Marinda Anderson and Pun Bandhu, who portray all the other characters in the play) have nominated him to log into her bank statement on a regular basis so that he can report back on the expenditures they need to cover: $60 on dog grooming; $4.15 at Starbucks; $3,000 to the Albany Symphony Orchestra.

(© Joan Marcus)

Ida was the wife of a minor politician (her second husband, who was not the father of her children), and she behaves as if she's always stepping into a Manhattan cocktail party. "We saw Leonard Bernstein socially," she informs a telemarketer for the symphony. We don't know whether to believe her or not, since Ida has long passed the stage where fact blends with fiction. We do recognize her as someone who knows how to make a first impression.

Dunagan endows Ida with an antique charm that she holds firm to, even as her changing circumstances make it ever-more ridiculous. She's like Blanche DuBois without the nymphomania. She's the type of woman you would love to sit down to tea with, which makes it all the more maddening that she seems so starved for real human contact. "You know, dear, I bought a jacket in 1975 at Bergdorf in New York City. Purple corduroy. Nothing has matched that jacket in 40-some years and now: BAM," she tells a sales associate at Talbots as she eyes a pair of purple corduroy pants. She proceeds to pepper Ronette (the saleswoman, played by Anderson with gentle patience) with compliments and anecdotes about her time marching with Martin Luther King. Costume designer David Hyman exposes her half lie by putting her in two very different shades of purple when she finally assembles the outfit.

(© Joan Marcus)

Director David Cromer's production is full of such subtle yet confident visual storytelling. As if to signify their frustrating inaccessibility, Allen and Jeremy lurk upstage, their bodies partially obscured. Laura Jellinek's dynamic set looks like an unfinished basement, but it transforms into a dozen other spaces over the course of the play. Sound designer Mikhail Fiksel and lighting designer Bradley King give us a palpable sense of Ida's mental deterioration during a sequence of disorienting scenes that are played half in the dark. Cromer's shrewd use of lighting is even more powerful in collaboration with King: A fluorescent flicker instantly sets the mood for a depressing scene in a sushi restaurant. Sure enough, Ida and the Son spend the next several minutes nibbling their rolls in silence as he occasionally checks his phone.

We would be inclined to hate The Son were it not for Friedman's remarkably sympathetic performance. He plays a man who mostly keeps his emotions walled up, a behavior developed from experience. Cracks occasionally appear, like when he's forced to answer a series of increasingly invasive "security questions" in order to access his mother's bank account. Posner turns these moments into heartbreaking and hilarious poetry. The backstory that emerges leads us to understand Ida as a woman whom strangers love, but perhaps only because they never have to get any closer than a first impression.

It's easy to take multiple sides over the course of The Treasurer. Posner has created a clear-eyed portrait of the tension between perception and reality that has harrowing implications for the way we age in America. Don't be surprised if you see yourself in it.

(© Joan Marcus)