(© Joan Marcus)

Sibling rivalry has been a central theme of Western mythology since Cain and Abel. Sam Shepard puts a uniquely American spin on that timeless story in True West, now receiving a Broadway revival from Roundabout Theatre Company at the American Airlines Theatre. This is the second time the play has appeared on Broadway, following a 2000 run at Circle in the Square in which John C. Reilly and Philip Seymour Hoffman alternated the lead roles. This new production from director James Macdonald stars Ethan Hawke and Paul Dano in fixed roles, playing brothers who have taken very different roads in life, but somehow end up right back in the same place: trapped in a showdown that will likely end with one of them dead. It sounds more thrilling than it actually is.

That has little to do with the story, which is one of Shepard's best: Screenwriter Austin (Dano) has retreated to his childhood home in Southern California's Inland Empire while Mom (Marylouise Burke) is on vacation in Alaska. He's working on a big project for producer Saul Kimmer (a wooden Gary Wilmes) and is hoping for a place to concentrate. Fat chance: Older brother Lee (Ethan Hawke) has also come home following an extended stint drifting through the Mojave Desert. Lee claims he tried his hand at art, but found burglary more lucrative. "No future in it," he says of creative work, glaring at his brother seated behind a typewriter. But when Lee takes Kimmer out for a round of golf and convinces him to back his "true-to-life" Western-movie treatment about two men chasing each other through "tornado country" (a story that Austin finds stupid and contrived), the brothers become unwitting (and unwilling) artistic collaborators.

(© Joan Marcus)

It's hard not to see an allegory of America in this story of a member of the creative bourgeoisie and his downwardly mobile brother, trapped in a poisonous embrace. Families like this actually exist, as Americans rediscover annually at their Thanksgiving shouting matches. In this most realistic of his plays, Shepard captures the surreal nature of American life by showing how much the comfortable Austin covets Lee's outlaw life in the desert, and how easily Kimmer is hoodwinked by the big lie of Lee's "truth." It seems not coincidental that the week after True West premiered at San Francisco's Magic Theatre in 1980, the Republican Party nominated for president a movie cowboy running on the slogan, "Let's Make America Great Again." Our national love affair with the maverick hawking fraudulent nostalgia is long and fraught.

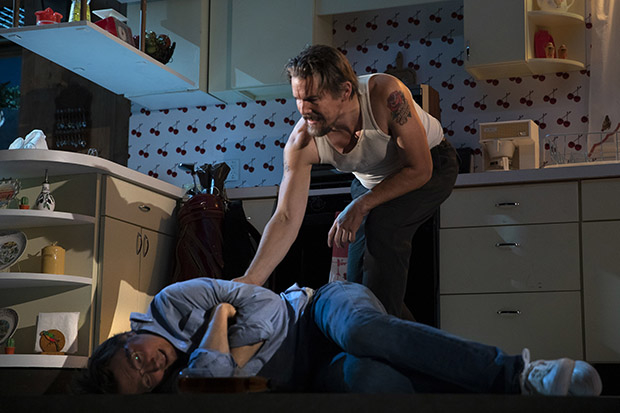

Unfortunately, the performances in this True West have a false ring about them: While we expect Austin and Lee to be polar opposites, there's little fraternal gravity pulling Hawke and Dano back to a shared past. Hawke plays an aging cowboy with a whiny rasp, while the inexplicably quirky Dano feels like he just stepped out of a canceled ABC Family sitcom. Perhaps in an effort to affect the creeping surrealism of Shepard's text, Macdonald has directed his two main actors to reach for bigger, ever more ludicrous performances in the second act. Hawke and Dano execute their pratfalls with technical mastery (excellent work by fight director Thomas Schall), but these physical non sequiturs rarely feel grounded in anything. Only Burke, as their flustered yet compliant mother, achieves a performance that feels utterly plausible in its eccentricity.

(© Joan Marcus)

The designers have created a handsome production, but they are co-conspirators in this slack affair: Mimi Lien's kitchen-cum-breakfast-nook set projects California dreaming, all the way down to its cherry print wallpaper; but it sits far back from the audience inside a false proscenium, making the characters look like mannequins in a Natural History Museum diorama. Jane Cox illuminates the room in moonlight, and Bray Poor underscores the restless night with the sound of aggressive crickets and the distant laughter of hyenas. Any tension built in these scenes is squandered during the transitions, in which vanity lights surrounding the darkened stage glow as we listen to instrumental Hank Williams. These long blackouts give the stagehands time to shift the scenery and the actors time to change (no element better tracks the passage of time than Kaye Voyce's increasingly soiled costumes). They also give our minds a chance to wander off, and many audience members doubtlessly take the opportunity.

Considering the life-and-death stakes, True West shouldn't feel as dull as it does. Still, if you can look past the lumbering production and showboating performances, you might discern the uncomfortable truth about the hostile codependency that governs our American family.