(© Carol Rosegg)

At the beginning of Qui Nguyen's Vietgone at Manhattan Theatre Club, an actor purporting to be the playwright claims, "Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. That especially goes for any person or persons who could be related to the playwright, specifically his parents…who this play is absolutely not about." Who is he fooling? Vietgone is the riveting story of the Nguyens' escape from Vietnam and budding romance in an Arkansas refugee camp. Beautifully conveyed through director May Adrales' unapologetically theatrical staging, Vietgone makes you believe that epic tales of heroism and loss exist all around us in this nation of immigrants.

Nguyen is the co-founder of off-off-Broadway geek theater troupe Vampire Cowboys and creator of such works as She Kills Monsters and Alice in Slasherland. Heavily influenced by comic books and action movies, Nguyen's plays are always heavy on ass-kicking stage combat and light on maudlin introspection. Vietgone is no exception, but the personal nature of the play and a structural refinement in Nguyen's writing results in an emotional resonance unprecedented in his work.

(© Carol Rosegg)

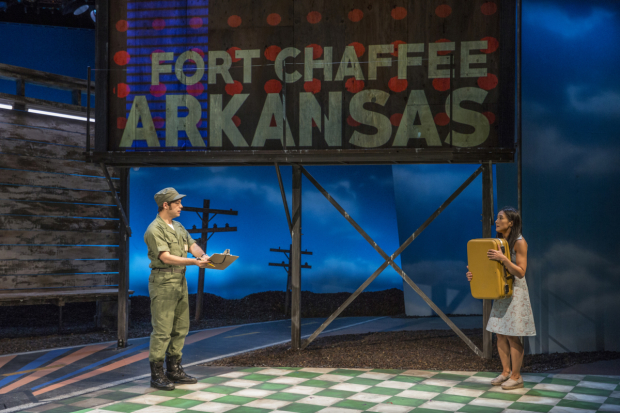

The story begins in 1975: Quang (Raymond Lee) is a captain in the South Vietnamese air force. He spirits a helicopter full of fleeing Vietnamese to an American aircraft carrier during the chaotic fall of Saigon, but he is unable to return and rescue his wife and children. Instead, he and his best friend, Nhan (Jon Hoche), are taken to a refugee camp in Arkansas where he meets Tong (Jennifer Ikeda) and her mother (Samantha Quan). While mom is totally over it from the first minute, Tong is enthusiastic about becoming an American, describing herself as "the sheer opposite of every Vietnamese woman on the planet."

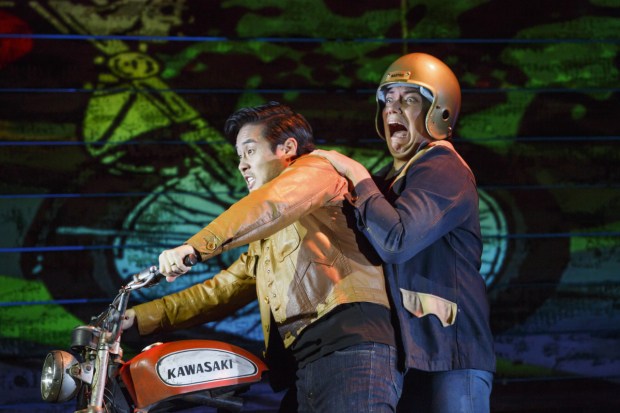

Tong sees Quang merely as an outlet for her sexual desires; she doesn't believe in love or domesticity. At first, this arrangement works, but their mutual attraction grows beyond lust. Despite this new romance, Quang embarks on a cross-country motorcycle trip just so that he can catch a plane to Guam, and hopefully get back to Vietnam to save his family.

(© Carol Rosegg)

As any fan of American rom-coms (or Shakespeare) can probably guess by now, Quang and Tong are made for each other; but considering that both still have friends and family back in Vietnam, even a happy ending will necessarily come with a certain amount of tragedy. Every triumphant moment is tainted with survivor's guilt, which Tong and Quang unpack in several lyrically astute raps numbers (set to Shane Rettig's catchy and tuneful original music). Nguyen's clear-eyed recognition of the realities of war is rare, refreshing, and definitely speaks to a dramatist who has matured…but not too much.

The show is still chock-full of thrilling fight sequences (with ninjas) and toilet humor. A language convention has all of the Vietnamese characters speaking perfect (if profane) English while all the American characters speak in an incoherent patois: A typical line reads, "Whoop whoop, fist bump. Mozzarella sticks, tator tot, French fry." Not only is this very funny, but it puckishly subverts the Hollywood practice of having vaguely ethnic actors improvise foreign-sounding dialogue: We are the nonspecific foreigners in this story.

Nguyen's script tends to cinematically jump back and forth in time, hopping across oceans at a moment's notice. Adrales keeps the time and place crystal clear with the help of projection designer Jared Mezzocchi, who projects the time and place on a giant billboard in Tim Mackabee's highway-themed set. Mezzocchi accents the stage picture with his stylish illustrations, which give the show the feeling of a graphic novel and turns the rap numbers into live music videos.

This five-person cast is game for all of it, with the three supporting actors taking on multiple roles with the help of Anthony Tran's essential costume design. The chameleonic Paco Tolson changes costumes more than anyone in the cast, playing the author, two of Tong's dweeby boyfriends, and a whole host of American stereotypes. Quan is hilarious as Huong, Tong's salty mom. Hoche is Cartmanesque as Nhan, but completely heartbreaking as Tong's little brother, Khue. We can see heightened versions of real relationships in all of their interactions, which straddle the line between authentic and absurd.

(© Carol Rosegg)

Most of all, thanks to sensitive and multilayered performances by Lee and Ikeda, we come to see Quang and Tong as superheroes: flawed and scarred, but undeniably incredible in their perseverance over adversity. Sitting at his kitchen table in 2015 during the play's final scene, an elderly Quang rejects the conventional wisdom that the involvement of American soldiers in Vietnam was a travesty, stating, "Many of them died so I could live — so I can be here right now." It's a rare perspective to receive floor time in an off-Broadway theater and just one of many little acts of bravery in a play overflowing with courage and compassion.