You Can't Stop the Beat! How Orchestras of Hamilton, Allegiance, and More Got Their Sound

Meet the orchestrators behind ”Shuffle Along”, ”She Loves Me”, and more, and uncover the facts about this mysterious profession.

(© David Gordon; Miguel Munguia)

They might not be household names, but Robert Russell Bennett, Sid Ramin, and Jonathan Tunick have had storied careers on the Great White Way in a profession few fully comprehend. They are the ones who made the pit orchestras sing with the romantic strings of South Pacific, the blaring horns of Gypsy, and the menacing percussion of Sweeney Todd. They are orchestrators, a job that is simultaneously one of the most important in the theatrical world and also one of the most confounding.

"So many people don't know what to make of it," says Lynne Shankel, a two-time Drama Desk Award nominee who worked on Altar Boyz, as well as the new George Takei-led Broadway musical Allegiance. It's a job so enigmatic, in fact, that it didn't even have a category at the Tony Awards until 1997 (when Tunick won the very first statue for Titanic). As recently as 2012, it was still viewed with such tenuousness that the Drama Desk Awards removed the category from contention that season, only to reinstate it amid pressure from the community.

"A lot of people think what an orchestrator does is take a piano part that a composer and arranger put together and just assign notes on a page to different instruments like some kind of weird musical secretary," Shankel adds. In fact, "That's literally what it is. You look at the notes on the page and you decide what instruments play what note. The thing is, if I actually did that, everything would sound really closed and very small."

So what does an orchestrator really do? "An orchestrator provides color and texture to a piece," Shankel says. "I take whatever the piano-vocal arrangement is and I'm thinking about how I can make this piece sound full. Do I want to make it sound lush and sweeping? Do I want to make it feel dry? A lot of that has to do with different things. The first step is figuring out the musical language of the show."

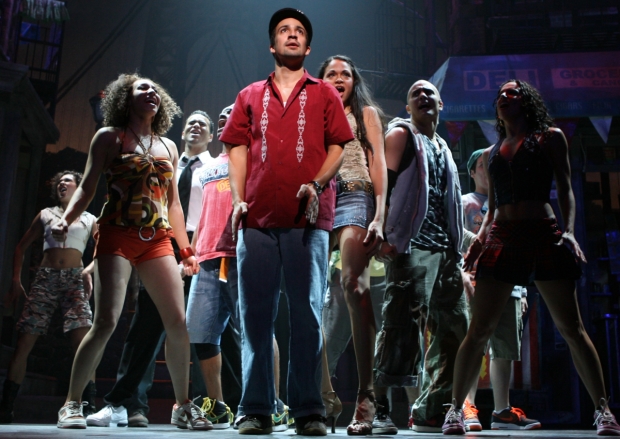

(© Joan Marcus)

"The Room Where It Happens"

The musical language of the show begins with the song itself. "Lin[-Manuel Miranda] writes the music and lyrics," says Alex Lacamoire, the Tony-winning orchestrator behind In the Heights and this season's Hamilton. "He has the bones of the song. This is the title, this is how the chorus goes, and this is the chord progression underneath it."

Next, the song is sent to an arranger, a person who "decides what the feel is," Lacamoire continues. "Arranging can be anything from deciding how fast [the tempo is] to putting a rock beat to a standard. The Beatles recorded "With a Little Help From My Friends," and then Joe Cocker did his version. He slowed it down and made it much more gospel. That's an arrangement of a song."

The result is a fuller version of the song written for piano. "In the Broadway genre," says Larry Hochman, the Tony-winning orchestrator of The Book of Mormon and a nominee last season for Something Rotten!, "the most typical scenario is: I receive a very good sketch that shows me the harmonies and, to ninety percent, the most important melody lines in the orchestra. The piano part I get would guide me to a large degree of what the orchestra should be playing." He or she then translates it into an orchestral sketch, complete with instrumentation.

''The Sound of Music"

"It's hard to describe how I come up with a sound," Hochman notes. "All of the aesthetic choices are, to a great degree, married to the dramatic situations. It's all running through my mind as I'm working on one phrase after another."

It's a collaborative process. "Generally," says Daryl Waters, the Tony and Drama Desk winner behind sounds of Memphis and this season's upcoming revival of the 1922 musical Shuffle Along, "It's [about] talking to the composer and director to make sure that I'm understanding as much as possible what they want in terms of the feel and whole emotion of the piece. From there, I take the overview of what I think it should feel like and do the big picture, and then I start filling in the details."

Both God and the Devil are in the details. A show can be made or broken by how it sounds. "I was thinking [Hamilton] sounded like a pop band and a string quartet," Lacamoire says. "I needed the drums and bass and guitars and keyboard at the center of it. I have a live drummer and a guy on percussion playing mostly electronic sounds, the snaps, and the handclaps, and the record scratches. I knew we were going to have this contemporary digital element, [so] I wanted the string quartet to represent the eighteenth century, the natural sound, something you don't need to plug in." Even that was decided in collaboration with composer Miranda. "Lin wanted the strings to be to Hamilton what the horns were to In the Heights."

In the case of Allegiance, which is set during the period of Japanese internment during World War II, "We're playing with a lot of Japanese flutes and Asian percussion [instruments] to get as many authentic ethnic elements as we can," Shankel says. That's being fused "with the period side of it, the 1940s big-band [sound]. We have some of that, as well, and that's more classic musical theater."

The orchestrator can also suggest how many players a particular show should have. "The number of players is recommended by me, but within the limitations of the budget and size of the pit in the theater we'll be in," Hochman says. "I might say I want twenty-two pieces, and the producer will want to keep it down to fourteen players. There are compromises to get it down. I come up with a plan and it has to be approved by the musical director, composer, and producers."

"It's about trying to find the balance of what works artistically and what's economically feasible," Waters adds. "The Music Box [where Shuffle Along will play] provides a challenge because it's a relatively small house. It would be nice to have fourteen pieces, but we'll likely end up with twelve, which is still a nice sound." To create his orchestrations, he's looking at the surviving originals from the 1920s. "It's amazing. They had bassoons, flutes, French horns, a brass section, and a lot of strings. That's the other thing, finding some way to cut that down and not lose what it was, while working within the practical considerations of 2015."

"To Thine Own Self"

If [listeners] have a natural resonance with a particular song," Lacamoire says, "yes, the song is what will move them, but the sound of the orchestration is what's going to push it over the edge." Lacamoire knows this first hand, having fielded compliments on social media about "the swelling strings during Angelica's lyrics in 'Take a Break'" and the "freaking banjo in 'The Room Where It Happens'" since the show's cast album was released.

And no matter how acclaimed they may be, there's still some self-doubt involved. "I'm not really sure any time I'm about to start an orchestration that I'm doing it right, or that they'll be happy with what I do," Hochman says. "Only when they've heard it and they've liked it that I'm convinced it'll be all right. I was very happy to hear John Kander tell me one day, 'I never wrote a show that I knew how to write.' At that moment, I realized I'm not the only person who feels how I do. If you've written in a way that the composers say it's what they wanted to hear, that is successful."

So what do people really need to understand about the art of orchestrating and the unique sound each orchestrator brings to his or her work? "It's cool to know that decisions were made to have a song sound the way it sounds," Lacamoire continues. "It's hard for people who aren't musicians to really understand that. People need to know that it's not arbitrary, and it would have been different if someone else did it. The songs are elevated because of the decisions an orchestrator makes."

(© larryhochmanmusic.files.wordpress.com)